The Authors , 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

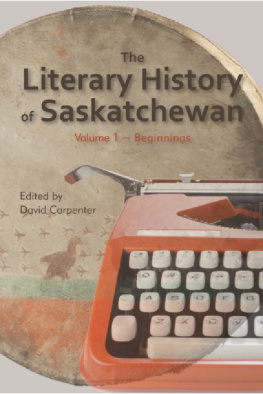

Selected and Edited by David Carpenter

Designed and typset by Susan Buck

Printed and bound in Canada at Houghton Boston

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

The literary history of Saskatchewan / edited by David Carpenter.

Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

Contents: v. 1. Pre-1980.

Issued also in electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55050-515-3 (v. 1)

1. Canadian literature (English)--Saskatchewan--History and

criticism. I. Carpenter, David, 1941-

PS8131.S3L58 2013 C810.9'97124 C2012-907250-8

ISBN 978-1-55050-537-5 (PDF : v. 1).--ISBN 978-1-55050-719-5 (HTML : v. 1)

1. Canadian literature (English)--Saskatchewan--History and criticism.

I. Carpenter, David, 1941-

PS8131.S3L58 2013 C810.9'97124 C2012-907251-6

Available in Canada from:

2517 Victoria Avenue

Regina, Saskatchewan

Canada S4P 0T2

www.coteaubooks.com

Coteau Books gratefully acknowledges the financial support of its publishing program by: The Saskatchewan Arts Board, including the Creative Industry Growth and Sustainability Program of the Government of Saskatchewan via the Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport; the Canada Council for the Arts; the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund; and the City of Regina Arts Commission.

To Anne Szumigalski and Gary Hyland:

may our conversations with you

and with your poems

continue to the very last day.

Literary Nonfiction in Saskatchewan

MYRNA KOSTACH

Definition

Literary nonfiction is the preferred term for a genre known variously as creative nonfiction, literary journalism, narrative prose, creative documentary and nonfiction novel. It has its contemporary roots in the New Journalism of the 1960s and 1970s when, in magazines and books, writers of nonfiction developed a style of journalism characterized by the use of subjective and fictional elements so as to elicit an emotional response from the reader, to cite the definition of the Oxford Canadian Dictionary. Its materials are documentary, its techniques novelistic and even poetic. It is increasingly the practice not to hyphenate the term nonfiction, on the ground that it is a genre in its own right, not a non-genre.

Although such a hybrid genre has been practised at least since the eighteenth century, it still provokes controversy whenever readers or re viewers expose as made up what they had assumed to be factual. The point is that, as a genre, it occupies a wide spectrum of types, from the point-of-view reportage of New Journalism; to narrative-driven travel writing, memoir and biography; to the reflective or metaphysical or lyrical essay; to boundary-breaching experimental prose-poetry. (The factualness of facts is more properly the concern of journalism.) Publishers have got into the habit of signalling a work of nonfiction, literary or journalistic, by adding a subtitle, especially when the work in question is a hybrid of several styles; works of fiction and poetry never have subtitles, unless by ironic intention.

Wolf Willow as Ur-text of Literary Nonfiction

Wallace Stegner (190993) first published Wolf Willow: A History, a Story and a Memory of the Last Plains Frontier in 1955, and it has never been out of print. It has become a classic of western Canadian and American literature, and, though Stegner spent most of his life in the United States and went on to write a lot of fiction, his output of nonfiction, mainly nature and landscape writing, remained impressive.

Wolf Willow can now be read as the source text for literary nonfiction in Saskatchewan of the past half century. For example, what I call its apparatus has become typical of the genre. The book has a map, lists and literary citations; library staffs and friends are acknowledged, as is a grant for Anthropological Research and a fellowship to the Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences, all of which confirm the works rootedness in objective nonfiction. But the very subtitle signals that Stegner has more than one intention for his material: his work is a documentary (history), a narrative (story) and a memoir (memory).

Perhaps anticipating objections to the occasional warped fact, Stegner explains that he has done so in the service of the fictional or poetic truth that I would rank a little above history. Even a literature based on fact and evidence reaches for a transcendent effect. The publishers blurb (in the 1977 edition) calls it an uncommon book because it combines fiction and non-fiction, history and impressions, childhood remembrance and adult reflection. Its language gives music and excitement to wisdom... All of which encapsulates what has come to be known as literary or creative nonfiction.

But Wolf Willow is the prototype. In the opening chapter, The Question Mark in the Circle, already on page four we are in the territory of the first-person narrator as full-throated storyteller, Stegner himself, writing from the point of view of a middle-aged pilgrim. Revisiting the town that he calls Whitemud (in fact Eastend) on the eastern flank of the Cypress Hills, he launches into the story of the cowpuncher named Buck Murphy, then into history, geography and geology. This is followed by travelogue, lyric landscape writing, re flection, reminiscence and imagined scenarios. In First Look, we have the 1805 Lewis and Clark expedition on the Missouri reimagined and the entire history of the fur trade in Canada summarized in one lyrical paragraph. The topography, geology, biology, paleology, meteorology, ethnology and cartography of the Cypress Hills are scooped up in five pages of The Divide. In Carrion Spring, the classic text within the classic, much of the riveting drama of the terrible winter of 190607 is told in dialogue.

The structure of the pieces within the book is a constant juxtaposing of elements; because not linear or expository, the seeming unreality of the narrative feels fictional. But that is really a function of memory, which, Stegner tells us, because it is not shared seems fictitious. That is an interesting if implicit proposition: we can know nonfiction by the communal (shared) memory. Memory is one of Stegners big subjects, its repression and denial, the ambivalence of the rememberer between wanting and not wanting to remember, its return to beginnings. In Wolf Willow , the narrators reflections on reality and memory, past and present, history and literature are all provoked by his reflections on his boyhood in Whitemud, and from this locale if I am native to anything, I am native to this he spins out all the big topics and tropes of what is today recognizably Sask Lit: the panoramic land, the connection be tween place and memory, the lost because unstudied past (we never so much as heard the word mtis ...), the excitement of recovering it, the tragedy of the First Peoples starved off the plains, the glorification of the pioneers who displaced them (after all, what other history and what other mythic figures are so intimately theirs?) and, from the point of view of a literary history, the disquieting notion that Saskatchewan has been the production of words spoken and attitudes struck by ro mantic philosophers and poets.

Writers and Texts

The literary nonfiction under consideration here is discussed according to types, none of which is a pure form and often overlaps with others: travelogue (McCourt, Abley); nature and landscape writing (Savage, Herriot, Butala, Gayton); personal essay (Ratzlaff, Safarik); narrative reportage (Siggins, Simmie, Butala); memoir (Campbell, Rigelhof, Cariou, Calder, Wiebe, Crozier).

Next page