Fortress 64

The Castles of Edward I in Wales 12771307

Christopher Gravett Illustrated by Adam Hook

Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic

Contents

Introduction

The castles built by Edward I in Wales rank amongst the finest military structures in Europe. As the English king determined to stamp his authority on the province that refused to yield quietly, he directed the building of enormous structures that were as much a statement of power as they were defences.

Wales had been a target for English kings even before the Norman Conquest of 1066. Welsh princes interfered in the politics of Anglo-Saxon England, while English rulers and lords took their opportunities to invade, skirmish across the marches, or even settle along the coasts. After the conquest of 1066 the Normans settled in both north and south Wales and built their castles. English settlements were consolidated until Wales was considered a principality owing fealty to England. This, of course, was carried out without actually asking the Welsh how they felt, so it was not surprising that they wanted a say in the matter. In the north of the country was the principality of Gwynedd, with its natural stronghold of Snowdonia; further south and east was the principality of Powys. Between them lay an area bounded by the River Conwy on the west and the Dee estuary to the east, variously referred to as The Four Cantrefs (as it was composed of four districts) or The Middle Country. Welsh princes had fought over it, but from Chester had come English forces, ensuring that the Welsh and English won and lost the area for centuries. Welsh castles existed as well as English ones, but for permanent control the king would need to add further strongholds in this area. Edward I (12721307) was just the man to attempt this. A determined policy was set in motion to crush resistance once and for all.

Wales was a difficult place for campaigning, as English armies had discovered. The central part was mountainous and unsuited to cavalry and to heavily armoured troops. During the 13th century Llywelyn the Great and his grandson, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, caused a great deal of trouble to Edward. Whilst prince, Edward had lost his lands in north Wales, since the Welsh had allied themselves with his fathers enemy, Simon de Montfort. Adding insult to injury, Edward had been captured with his father after the battle of Lewes in 1265. When he returned to England as king in 1274 it was obvious that Llywelyn was spoiling for trouble, refusing to attend the coronation and plotting to marry de Montforts daughter, who ended up being captured when the English seized her ship in the Bristol Channel.

Edward declared war in November 1276 and summoned the host to meet at Worcester on 24 June 1277. However, he had already organized his forces for war. The castle of St Briavell in the Forest of Dean was a major maker of bolts for crossbows; ships were drawn from the Cinq Ports and other areas. Edward designated three military captains to organize defence and raise militias, and to take charge of troops sent to them: in Chester and Lancaster a companion of the king, William Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick; Roger Mortimer in the shires of Shrewsbury, Stafford and Hereford; and Pain de Chaworth, who held a captaincy in west Wales, this being then taken over by the Earl of Lancaster in April 1277. They could also negotiate with local Welsh lords in order to enlist native soldiers into the ranks. By spring 1277 their bold methods had taken back everything Llywelyn had seized in the Marches from the borders of Cheshire to Cardigan Bay. Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, recaptured his lands in Brecon, while the Earl of Lincoln took Dolforwyn and recaptured Builth. Two sons of Gruffydd ap Madog came to terms with Edward for north Powys, opening the way north and south of the River Dee. In the valley of the Tywi, Rhys ap Maredudd submitted to Pain de Chaworth and so Dryslwyn castle was available to the king. Carreg Cennen, Llandovery and Dinefwr were captured in June, the latter becoming an administrative centre. The new commander, Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, could now move north and by the end of July had seized Aberystwyth. Edward pushed Llywelyn and his influence out of east and south Wales and back to Gwynedd.

The kings successes allowed him to begin a castle-building programme at Builth, Aberystwyth, Flint, Rhuddlan, Ruthin and possibly Hawarden.

Other castles were strengthened in Wales and the Marches with small expenditure, such as Cardigan, Carmarthen, and Montgomery. Some existing fortresses were replaced, e.g. Rhuddlan replaced Dyserth, the latter built by Henry III.

A political settlement gave Llywelyns younger brother, Dafydd, extensive areas of land between the Conwy and Clwyd rivers; he was also allowed to repair Hope (Caergwrle) castle and make his headquarters at Denbigh. However, in 1282 Dafydd launched an attack on Hawarden castle, once again provoking a Welsh revolt. Edwards reaction was swift and sharp. Writs were sent out across England and also to Ireland, Ponthieu and Gascony, for supplies and men to gather at Chester; the sheriffs of 28 shires were to muster 1,010 diggers and 345 carpenters there by the end of May, less than two months after the revolt began. Three armies marched into Wales: in the north from Chester, in the centre from Shrewsbury northwards and from Montgomery westwards, and in the south from Carmarthen north-eastwards. Whatever Edward may have intended by his actions, the killing of Llywelyn that same year in an ambush near Builth allowed the king to put himself forward as the feudal heir to the forfeited land. The Welsh princedom was replaced by a royal English master. Denbigh was seized after a siege lasting for a month in the autumn, while Dafydd was captured in June 1283 and subsequently hanged, drawn and quartered. The king set about organzing the building or rebuilding of such lordship castles as Denbigh, Hawarden, Holt and Chirk, to guard his rear, and could now march into the centre of Gwynedd. The castles of the Welsh princes such as Castell y Bere, Criccieth and Dolwyddelan were seized, and the royal fortress ring expanded in 1283 when work began on major new castles at Conwy, Harlech and Caernarfon. Edward now had the great engineer Master James of St George in his employ, and these new castles showed a strength of purpose that is less evident in those of the first campaign. In August and September the Cinq Ports fleet was instrumental in placing forces in Anglesey and Edward ordered a bridge of boats to connect to the mainland near Bangor, so that a central army under Otto de Grandson could land near Caernarfon and then proceed to Criccieth and Harlech. Luke de Tany crossed in November only to be ambushed, with 16 knights and their squires drowned. The bridge was eventually finished, and was later deliberately destroyed once work was under way at Caernarfon and Harlech.

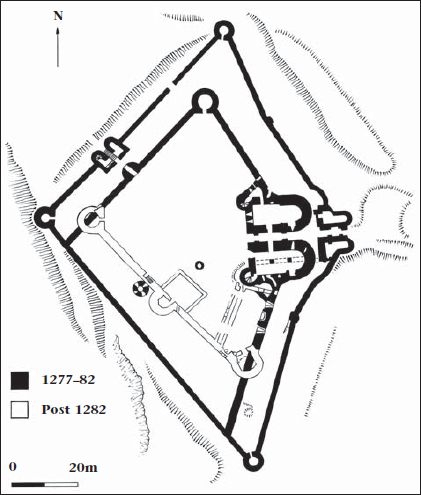

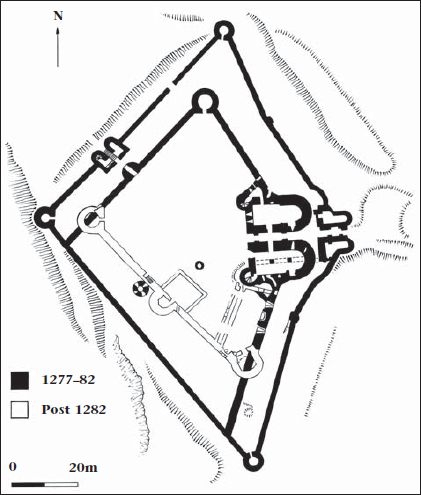

A plan view of Aberystwyth castle. Begun in 1277, it was of lozenge shape, and had a single inner gatehouse. It appears originally to have been of part-concentric plan, with only a single line of wall on the south-west side. However, after 1282 this side too was given an inner wall, achieved by building a circular (then D-shaped) tower along the southern wall of the inner curtain, with presumably another on the other side, the two joined by a new stretch of curtain to form a fourth inner side. The stretches of old curtain left in the newly formed outer ward were demolished. A mural tower was also added midway along the new curtain, overlaying a lime kiln, presumably used in the original construction works of 1277 onwards. The alterations were probably the work of Master James of St George after the capture of the castle following its partial demolition in 1282. (Adam Hook)