CONTENTS

Dedication

For Jane, who has helped more than she knows, and for Joanna and Ben who once lived within the friary precincts.

INTRODUCTION

Since writing my original Osprey volume on Bosworth in 1999, information about the battle and the fate of Richard III has greatly increased. From 2005 to 2010, the Battlefields Trust carried out detailed investigations to find the true location of the field, since several possible locations had been suggested. One aim was to discover the marsh around which the two armies had manoeuvred, so soil samples were taken from various possible sites, which disproved the theory that it lay around the foot of Ambion Hill, while a likely candidate was found some 2km west at Fen Hole. Finally, after numerous efforts by organized field walkers and detectorists, in March 2009, a 30mm round shot was found on the western periphery of the search area, followed by several other shot and relevant artefacts; the battlefield had finally been located. Further shot were found in 2016 and 2018.

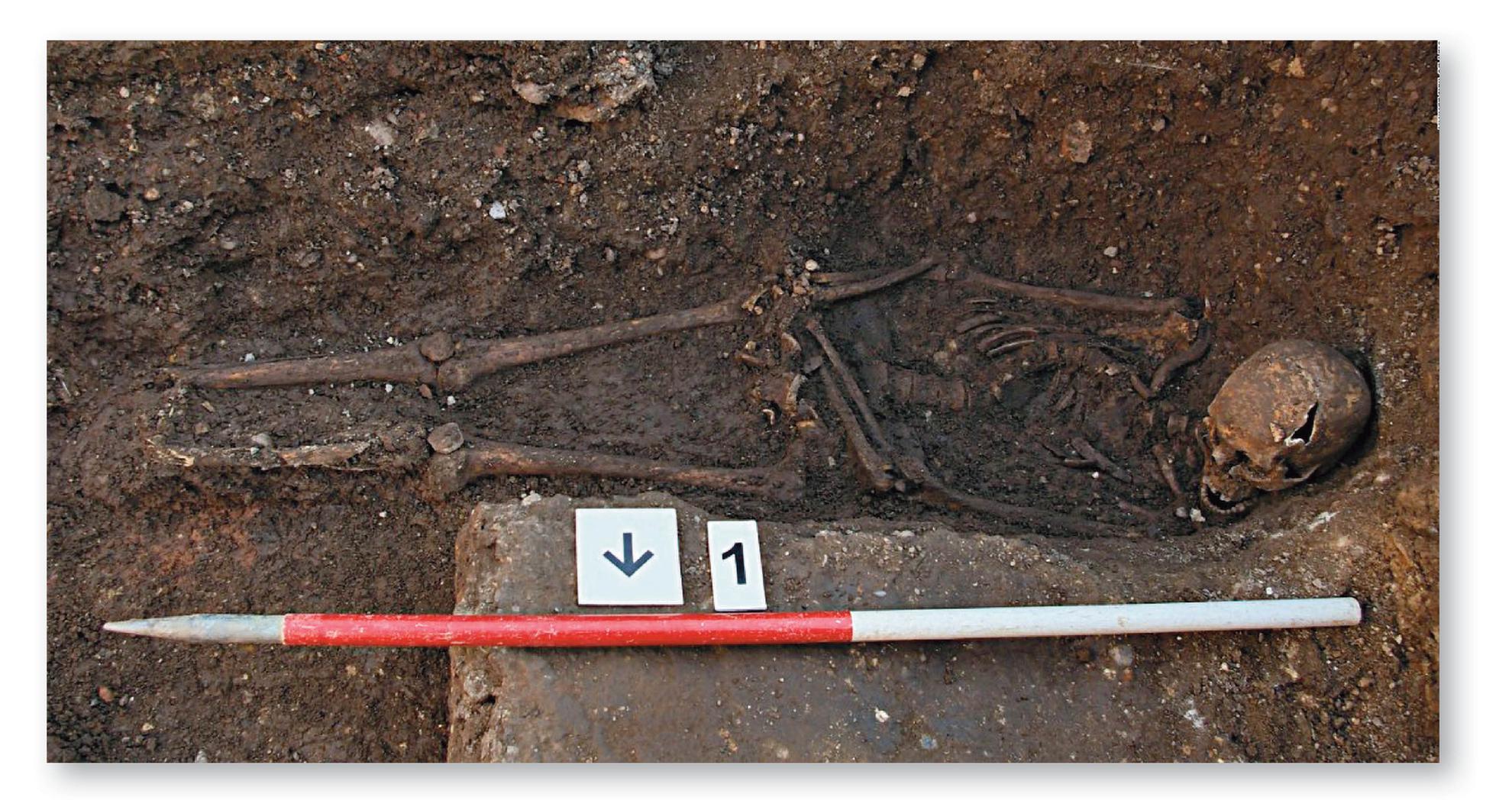

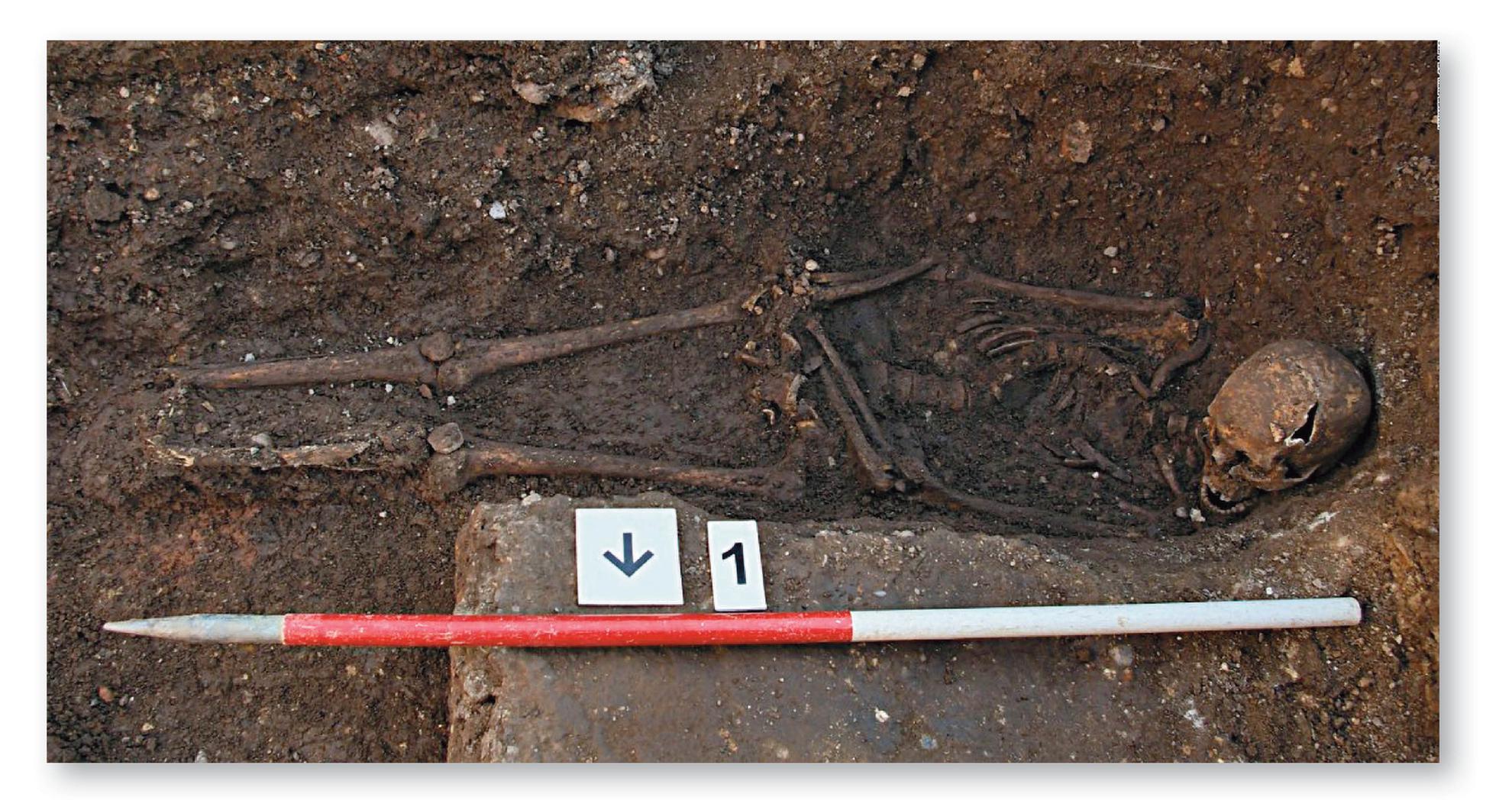

Meanwhile, in March 2011, Philippa Langley of the Richard III Society approached the University of Leicester Archaeological Services to try to find the remains of Richard III and the Franciscan friary in which he had been laid. When funding had been secured, the work went ahead, and, in September 2012, a skeleton was discovered under what had become a Leicester council car park. On 4 February 2013, it was finally confirmed to be that of Richard III. Study of Richards skeleton showed the curvature of his spine conducive with scoliosis, while trauma to some of the bones strongly suggested these were sustained during his final moments at Bosworth and immediately following his death.

SOURCE MATERIAL

Despite the discovery of the battlefield and artefacts, documentary evidence remains a vital addition. Contemporary chroniclers of the battle present problems, often differing in their details and from later writers. John Rous, a scholar and chantry clerk from Warwick, completed a history of England ( Historia Regum Angliae) in 1486, which provides some material. He was at first complimentary of Richards rule, but later became a great Tudor supporter. The other English source is the anonymous so-called second continuator of the Crowland Abbey Chronicle, of c.1486, probably written by someone in Richards administration, perhaps John Russell, Bishop of Lincoln. Hostile to Richard, it does not offer much information on the battle, although it does describe the reactions of the nobles in Richards reign. Perhaps the best contemporary commentaries come from Continental sources. An unbiased source for the battle is Jean Molinet, writing at the Burgundian court by 1504 and probably before 1490. At the French court, Philippe de Commines, probably writing at a similar date, provided an account of the expedition. Despite meeting Henry, he is not obviously biased and openly questioned his claim to the throne. The Castilian Diego de Valera sent a memorandum on English affairs to the Spanish court in March 1486 that includes a description of Bosworth, using some information provided by Juan de Salazar, a Basque mercenary commander sent by Emperor Maximilian to assist Richard and who stood near him during the battle, although de Valera obtained this via merchants; he is hostile to Richard because of his presumed usurpation. Interestingly, Molinet describes Salazar, but does not mention him at Bosworth. A fragment of a lost letter from a French soldier at Bosworth (the so-called Spont fragment) also provides tantalizing information. The will of Thomas Longe, who served the Duke of Norfolks son, the Earl of Surrey, was made on 16 August, six days before the battle, when he relates he is going to the kings host at Nottingham. Letters from men of rank are for raising troops, notably Norfolks request to John Paston. Similarly, most contemporary government papers or those of cities etc. that relate to the battle are calls for military service or reactions following Richards death.

Richard IIIs grave, discovered in 2012 in what had been part of the choir of Grey Friars Church. His skeleton can be seen in situ, the spine bearing evidence of the curvature of scoliosis. The grave was made slightly too small and his head is propped up in a corner, suggesting a hurried burial perhaps because of decomposition of the body. Following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the site was sold in 1536 and the buildings destroyed two years later. By the later 20th century, it had become a council car park. The Richard III Centre was built partly over the grave to preserve it. (Mathew Morris University of Leicester)

During the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII, the idea took shape that their dynasty saved England from war and from a tyrant.