First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Peter Hammond 2010

ISBN 978-1-84415-259-9

ePub ISBN: 9781844687589

PRC ISBN: 9781844687596

The right of Peter Hammond to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics

and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Preface

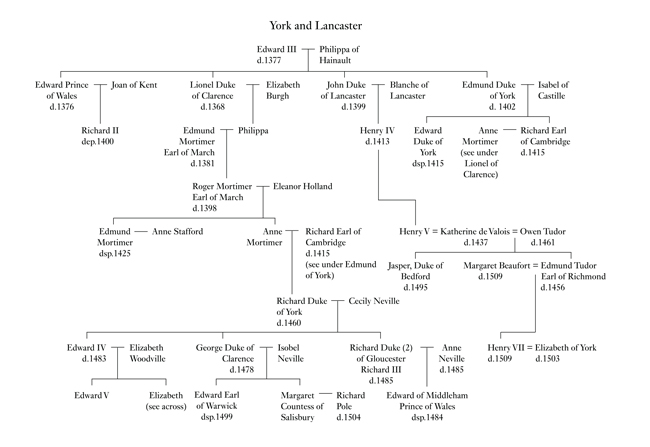

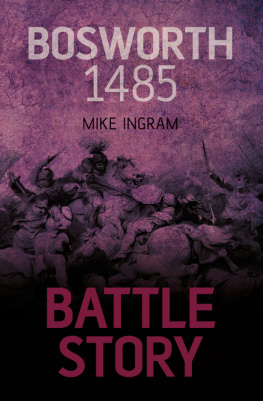

The battle of Bosworth was traditionally said to mark the end of the Middle Ages, and in at least one sense it did. It is of major importance in English history. A crowned and anointed king died there, the last king of the Plantagenet dynasty that had ruled England since 1154, to be succeeded by the first king of a new dynasty. In addition, it marked, if not the end of the Wars of the Roses, then the last throes of the struggles of the last 30 years, although contemporaries did not know that. Certainly after Bosworth the world changed radically.

In contrast to most battles in the Middle Ages, the battle of Bosworth is relatively well documented. There are several sources one of which, Polydore Vergils History , is very detailed which give us information about the course of the battle, although none of the sources is very clear on exactly where it took place and until recently many different places near its probable site near Sutton Cheney in Leicestershire have been proposed. Some of the early sources, notably Edward Hall in his Chronicle and William Burton in his Description of Leicestershire (1622), place it correctly on a plain. The most popular site, however, has been on and around Ambion Hill, a place first mentioned by Holinshed as the place on which Richard camped, and subsequently taken up enthusiastically by most seventeenth-century and later descriptions as the place where the battle was fought, particularly in William Huttons popular book The Battle of Bosworth Field (2nd edn, 1812). While taking up a defensive position on top of a hill was not unknown in the Middle Ages, there is no evidence that this battle was fought from a hill. None of the contemporary sources says this, nor indeed the later ones, but most writers from the late seventeenth century until recently have placed the battle somewhere near the hill in more or less likely places for a battle, and with equally puzzling maps. In 1990 Peter Foss examined the local evidence in conjunction with the documents and placed the battle on the plain between Ambion Hill, Dadlington, Shenton and Stoke Golding, although even Foss placed Richards army at the foot of the hill. He also found a place called Sandford, the name of the place at which Richard was probably killed. Fosss site recommended itself to historians until Michael Jones, writing in 2002, suggested that it was fought about 2 miles northeast of Merevale Abbey.

There is a small amount of circumstantial evidence for this suggestion, chiefly in the form of local place-names, such as King Dicks Hole, Bloody Bank and Royal Meadow, that might show that it was fought here but none of the names can be shown to date back as far as the fifteenth century and there is nothing definite to prove that this was the site of the battle. Henry certainly spent the night before Bosworth at Merevale Abbey, but that does not mean that the battle was fought near there. Pinpointing the actual site of the battle has taken a great deal of work in the area around the possible battlefield site, using modern scientific techniques and old-fashioned site-walking to track down the place where this important battle was fought. The results of this work seem to show that the battle took place on a fairly restricted site rather to the south and west of the others suggested. However, the results of the recent work are to some extent preliminary, and it may be that future results will give us a different picture and the battle will be found to have been fought on a slightly different site. Given the current results, it is unlikely to be in a totally different place. However, bearing this in mind (and the fact that future discoveries may change the picture somewhat), this account is based on the results to date.

In addition to not knowing until recently where the battle was actually fought, it has also had several names since 1485. The earliest record we have calls it Redemore or Redesmore. This is an entry in the minutes of the York City Council (the House Books), probably on 23 August. It is written at the end of an entry for 19 August on one folio and before the entry recording the death of Richard III at the top of the next folio, which

This book is about the events leading up to this important battle and gives a description of the battle itself. It is also an account of the reign of Richard III, although it is not purely biographical. It concentrates on the military aspects of the two years he held the crown, describing how he fought to ensure the safety of his realm and prevent invasion, and indeed to hold on to his crown. Following the events of Richards life from his coronation to his death, it is very apparent that from the beginning of his reign he was determined to maintain his position, which is of course what we would expect of any medieval king, but in the case of Richard III it does appear that his kingship had something of the nature of a crusade. He seems to have felt that he was responsible not only for the governance of the realm but for its moral well-being too. It has been suggested that he saw himself as having a moral duty and right to take the throne, perhaps because of the doubts cast on his brothers marriage, as a result of which Edward V (his brothers son) had no moral right to the throne, and that as a man of deep religious convictions, he persuaded himself or allowed Such a man would believe that for him to hold the crown was a Godgiven right. Richards various proclamations, particularly that against Tudor in 1485, are couched in very moralistic terms. It is also very apparent that he took every possible practical step to counter the threat of invasion and to meet it when it came. His actions were almost text-book in their thoroughness to raise men and to ensure that he could gather an army as quickly as possible. He always thought and acted as a soldier. At no point in his reign did he seem to have given way to inertia or despair, he responded to all the challenges arising and he fought, literally, to the very end.