To Francis Temple Bacon

Acknowledgements and thanks for permission to reproduce photographs are due to the Ashmolean Museum (3), Society of Antiquaries (1, 2, 10, 11, 12), Richard III Society, (5), to David Scuffam for his excellent drawings used as chapter endings, to Julian Rowe for the last of these drawings and for the magnificent reconstruction of Fotheringhay Castle.

Contents

by Peter Hammond |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

XI |

XII |

XIII |

XIV |

1. Henry VI, early sixteenth century, derived from a contemporary portrait. (Society of Antiquaries)

2. Edward IV, early sixteenth century. (Society of Antiquaries)

3. Elizabeth Woodville, perhaps painted as early as 1500. (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University)

4. Fotheringhay Castle, a reconstruction of its appearance in the fifteenth century. (Peter Hammond)

5. Richard III, a reconstruction of the face. (Richard III Society)

6. Richard III, Anne Neville and Edward of Middleham, Rous Roll.

7. Middleham Castle, a modern photograph. (Geoffrey Wheeler)

8. Baynards Castle, a drawing of the seventeenth century.

9. Crosby Hall, a reconstruction.

10. The Broken Sword portrait of Richard III, a propaganda picture dating from the reign of Henry VIII. (Society of Antiquaries)

11. Broken Sword portrait, X-ray photograph, showing high original (deformed) shoulder line and short withered left arm, as originally painted. Later over painting restored the portrait to a more normal appearance. (Society of Antiquaries)

12. Henry VII, probably painted in his life time. (Society of Antiquaries)

Chapter Endings: Heraldic Badges

1. Falcon and Fetterlock of York

2. Livery Collar of Edward IV, with roses between suns in 23 splendour and a pendant White Lion of York

3. Rose-en-Soleil of York

4. Livery Collar of Richard III, with roses between suns in splendour, and a pendant White Boar

5. Crown in Thorn Bush of Henry VII

6. Dragon of Henry VII

7. Livery boar badge from Middleham

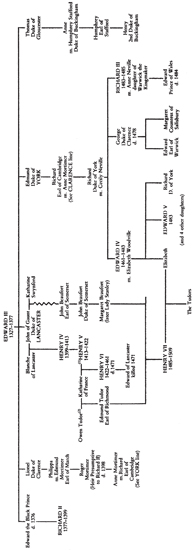

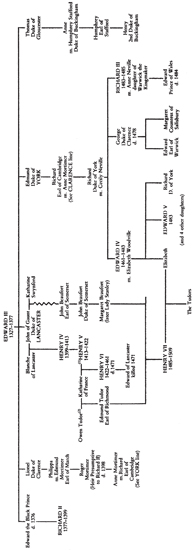

T HE H OUSES OF Y ORK

AND L ANCASTER

M rs Lamb wrote this book more than 50 years ago, in 1959. At that time few historians seemed very interested in the late middle ages. Since then there has been an explosion of interest in both the period and in Richard III, and many books and editions of documents have been published. The discovery of his bones in 2012 has fuelled this interest. When Mrs Lamb wrote the traditional picture of Richard as a hunch backed monster who murdered his way to the throne was still widely accepted, by the general public at least. Mrs Lamb had studied the period and Richard and made a complete transcript of the English portions of the Signet office register of Richard III, from British Library Harleian Ms. 433. She took over four arduous years to complete this work, also making name and place indexes to these portions. The existing edition of the manuscript is based on her work. Her work on this important manuscript, and her extensive reading convinced her of the defects in the traditional picture of the last Plantagenet king and she wrote this book.

In the years since it was published the perceptions of Richard have changed, Most historians would now accept Mrs Lambs common-sense view of Richard as a man, of his guiltlessness at least of the crimes he has been accused of committing before he became king, and of his desire for justice. Interestingly her claim (p. II) that a modern jury would consider that there was no case for Richard III to answer has been borne out in a televised staging of his trial on a charge of murdering his nephews. However there are still books being written which give a picture of Richard partly or largely based on the traditional picture, and the Betrayal destroys that picture in a clear and forensic manner. It also gives a clear account of the very complicated background to Richards life.

The increase in our knowledge of Richards life and times has also meant that some of Mrs Lambs statements need to be qualified in the light of recent research. The notes in this new edition are intended to update it without altering the form of Mrs Lambs references. The most recent work on the discovery of Richards bones and the proof that Richard was not deformed as traditionally described has been included. Mrs Lamb would have been very pleased.

Peter Hammond

January, 2015

Note

. Richard Drewett and Mark Redhead, The Trial of Richard III, Gloucester, 1984.

T he purpose of this book is to examine very briefly the foundations on which one of the most famous legends in English history has been built. I do not claim to throw any fresh light on the mystery which surrounds Richard III, neither do I propose to make an exhaustive survey of his life and times. Rather do I wish to trace the growth of the traditional legend from its conception through the main accepted sources, and to emphasize the doubtful nature of the basis upon which this elaborate and apparently circumstantial story was built a story which was widely accepted as incontrovertible over a period of nearly five hundred years. In fact, the evidence for the traditional picture of Richard is of such a flimsy and suspect nature that a modem jury would, I think, rightly consider that on it there is no case to answer.

V.B. LAMB

1959

1

W hen Edward IV died at Westminster on April 9th, 1483 he had been King of England for twenty one years and nine months with a short intermission in 147071. He inherited his claim to the throne from his father, Richard Duke of York, killed at the battle of Wakefield on December 30th, 1460, and there is no doubt that this claim was valid in law. The House of York was descended through the female line from Lionel of Clarence, third surviving (effectually the second) son of Edward III, whereas the House of Lancaster which it superseded derived its descent from John of Gaunt, the fourth son of the same King, and owed its possession of the throne to the usurpation of Henry of Bolingbroke, who had deposed his cousin Richard II, whom he imprisoned in Pontefract Castle where the unfortunate King met a diversely reported but undoubtedly unpleasant end, while Henry had himself crowned as Henry IV.

In 1460 the throne was nominally occupied by Henrys grandson, Henry VI, who had succeeded as an infant of nine months, and after a long and disturbed minority had grown into a saintly but feeble-witted man, quite unfitted to govern a turbulent realm. As a result the government of the country was in the hands of his wife, Margaret of Anjou, and her successive favourites, the Dukes of Suffolk and Somerset, whose relations with the Queen gave rise to considerable scandal. It was generally thought that her only son, Edward of Lancaster, was in fact the son of Somerset, a rumour which received considerable impetus when King Henry, on being informed of the birth of an heir, remarked that it must have been through the agency of the Holy Ghost. However pleasing such divine intervention might be to the saintly King, it was hardly calculated to inspire confidence in his subjects, a large proportion of whom were bitterly discontented with the oppressive rule of the foreign woman and her lovers. During the 1450s the country seethed with discontent and sporadic outbreaks of civil strife, and an increasingly large number of the people began to look to the Duke of York as the rightful King of England and their only hope of stable government. These hopes were dashed when the Duke was killed in a fight with Queen Margarets army at Wakefield, to be swiftly revived in the person of his son, Edward.

Next page