History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.

Sir Winston Churchill

History is always written by the winners.

Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code

In memory of my dear mother, Joan, who wrote to me that your love of history must stem from me as I always loved the subject at school.

First published 2015

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

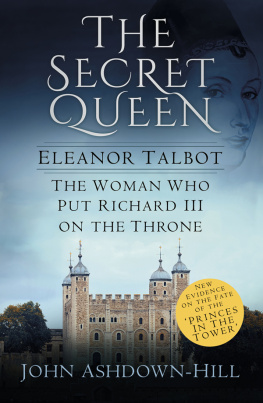

Copyright John Ashdown-Hill, 2015

The right of John Ashdown-Hill to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781445644677 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445644738 (eBOOK)

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

Contents

Introduction

No man should be judged by another.

The Cloud of Unknowing (written by an anonymous English priest, possibly from the East Midlands, c. 1390)

Richard IIIs life story was rewritten and in a thoroughly slanted light by the propagandists of his victorious opponents after his defeat and death at Bosworth in August 1485. Should anyone harbour the slightest doubt that such things still happen today, in the real world, they have only to look at how the story of the rediscovery of the kings remains in 2012 has been edited since that discovery was made. The authentic and true story of this search which was not led by anyone based in Leicester is revealed in Finding Richard III The Official Account. But editing of this true story seems to have been chiefly manipulated by the University of Leicester Press Office and its associates in order to claim maximum kudos in respect of the discovery, firstly for the university itself, and secondly for the city of Leicester. Evidence of this activity is presented in part 7 and the appendices (see below). As for the possible motivation for such conduct on the part of an academic institution in the somewhat unfavourable context of the modern world, that is examined in this books final chapter (Conclusions).

Attempts have also been made to edit the true story of the rediscovery of Richard IIIs remains by certain soi-disant professional historians, archaeologists and writers. Curiously, not one of the individuals in question was responsible for a single significant revelation, or for the discovery of any new evidence, relating to King Richard or his burial site. Nevertheless, these individuals presumably hoped that it would prove financially rewarding for them to cash in on the discovery once it had been made. It is also intriguing that one of them is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. His selective use of the terms amateur and professional appears to show remarkably little knowledge of the history of the Society of Antiquaries, or of the hugely valuable work done by its amateur Fellows in the past.

One forthcoming book on Richard III, due out in April 2015, has been written by the Grey Friars Project Team (that is to say, the team as currently defined by the University of Leicester), together with Lin Foxhall, head of archaeology and ancient history at the university, and journalist Maeve Kennedy of TheGuardian. Professor Lin Foxhall is basically a classicist. She is a reputable scholar in her specialist field though her reading and interpretation of medieval Latin can sometimes be questioned slightly (see below, chapter 2). Nevertheless, neither she nor Maeve Kennedy carried out any research on Richard III that contributed to the search project for his long-lost remains, or to the eventual setting in motion of the archaeological excavation of August 2012.

In precisely the same sort of way, the government of the usurping and essentially non-royal King Henry VII rewrote history from August 1485, in order to improve the standing of the new head of state. Henry VII had no valid blood claim to the English throne. The true Lancastrian claimant to the English throne in 1485 was either the King of Portugal or the Earl of Warwick. But Henry seized power by means of a foreign-backed invasion which culminated in the battle of Bosworth. He then legitimised his power seizure by causing Parliament to recognise him as king. His conduct in respect of his accession contrasts notably with that of his predecessor, Richard III, who, as we shall see, was not legitimised as sovereign post hoc factum, but rather was offered the crown in advance by the three estates of the realm. Full details of the true nature of Richard IIIs claim to the throne are offered below, in chapter 6.

One of the earliest and most obvious rewritings of history was, in fact, Henry VIIs repeal of the Act of Parliament which had recorded and confirmed the offer of the crown to Richard. That 1484 Act was repealed unquoted an unprecedented move in an ultimately vain attempt to ensure that no one in the future would ever be able to access the evidence which had led to Richard being offered the throne. To airbrush this evidence out of history even more effectively, Henry VII also forbade any copies of the original Act to be kept, under the threat of severe penalties.

Of course, the actions of Henry VII and his government were in no way unique. It would be nave to suppose that any ruler, of any historical period, who has been violently ousted by a political opponent, is, or has ever been, favourably reviewed subsequently by the incoming regime. After all, both the political role and the authority of the new regime are entirely based upon the predecessors downfall.

Examples of such rewriting of history can be found in every period of recorded history, from the ancient world to the present day. Indeed, in my own lifetime we have witnessed a number of examples, such as the ousting of the Pern government in Argentina (more than once), the overthrow of the Shah of Iran, and the fall of a number of other Middle Eastern regimes, not to mention the political controversy in Myanmar (Burma) and the way in which the government there has portrayed the opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. In all such cases the fallen regimes, or the outlawed political leaders, have been negatively portrayed by those who replaced them, or excluded them from power.

It is interesting to consider what these modern examples of the rewriting of history reveal. For example, the reign of Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi definitely had what can be seen as positive points, including the Shahs support of education and of womens rights. Of course, it also had what can be seen as negative points, such as the Shahs transformation of Iran into a one-party state. Problematically, however, many of his policies could potentially be viewed either positively or negatively depending upon the viewpoint of the observer or commentator. Policies which fit into this equivocal category include the Shahs support of modernisation and secularism, foreign support for his regime, and his recognition of the state of Israel. Another curious point is the fact that, during his reign, the Shah was criticised for holding political prisoners. Ironically, however, after his overthrow the number of political prisoners vastly increased. According to official statistics, Iran had as many as 2,200 political prisoners in 1978,