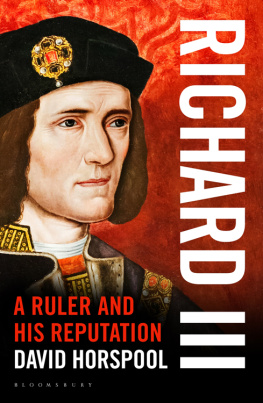

Richard III

A Ruler and His

Reputation

David Horspool

In memory of Christopher Horspool (19402013)

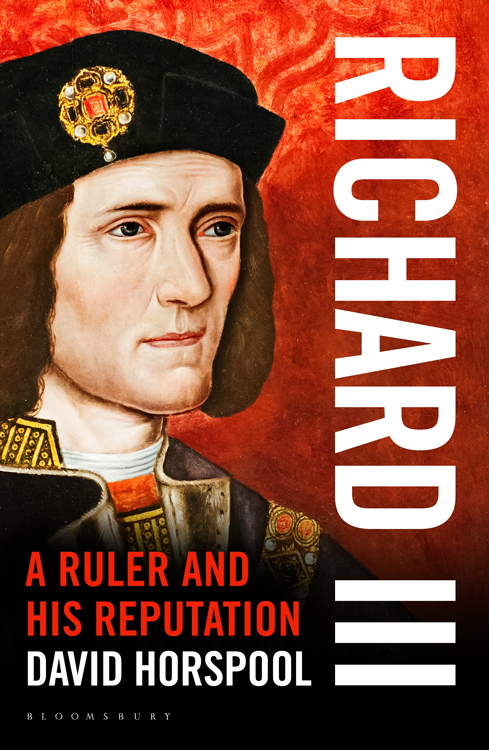

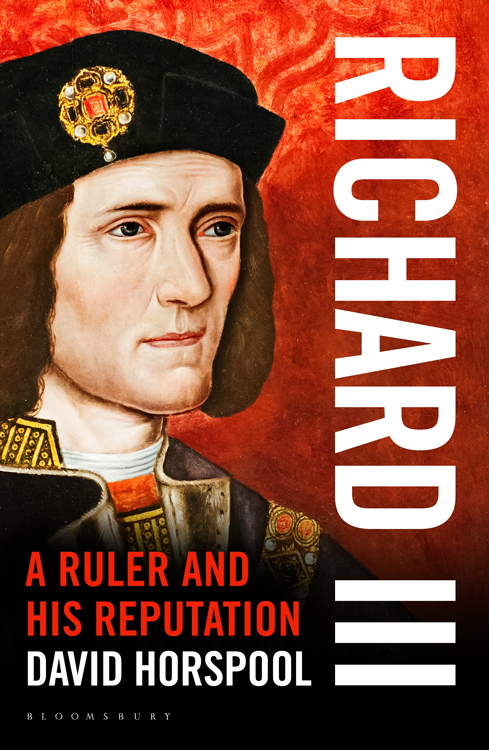

A famous portrait: a man gazes distractedly off to the left, his hands held lightly together in front of his chest. The eye is drawn to those hands. In a nervous gesture, the left thumb and forefinger pinch off, or on, the ring on the little finger of the right hand, one of three rings he is wearing. The man is sumptuously dressed and ornamented, his sleeves lined with fur, a ruby and pearl jewel in his hat, and a rich collar in which fourteen more rubies and twenty-four more pearls are visible. These are the trappings of very high status, but the sitter has none of the placid self-assurance associated with the wearers of such finery. His eyes seem those of a youngish man, perhaps in his early thirties. They are bright and keen, if mournful, while his skin is pale and his features are drawn. The lines on his brow and around the eyes age the face. Here is a picture of nervous energy, and of gnawing conscience.

This painting, hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in London, a detail of which is reproduced on the cover of this book, remains the most familiar of all images of Richard III, though it is not the oldest. It was painted long after its subjects death in 1485, probably around a hundred years later. It is based, like dozens of others that once decorated the corridors of great houses throughout the country, on a portrait in the Royal Collection, which was painted between 1504 and 1520 that is, also not from life. Intriguingly, despite the hints of troubled conscience, the National Portrait Gallery version is far more sympathetic than the earlier Royal Collection one. That portrait was touched up fairly soon after it was first done, to thin the lips and set the mouth in a hard line, and to raise the right shoulder only very slightly elevated in the National Portrait Gallery version rather more acutely. The skin in the Royal Collection portrait is sickly pale, almost yellowing, and the eyes are harder, while the thumb on the right hand, which is bent in the National Portrait Gallery version, seems to have sharpened into a point. This picture, recorded in the collections of Henry VIII and Edward VI, son and grandson respectively of the man who replaced Richard III on the throne, seems to have been painted to capture the classic Tudor view of Richard, as an incarnation of evil, a usurper and mass murderer, deformed in mind as in body. Here is the wicked uncle, killer of the Princes in the Tower (among others), awaiting his deserved comeuppance in battle against the rightful king.

The fact that the Tudors themselves kept a deliberately exaggerated version of bad King Richard on their walls is less puzzling than the fact that, towards the end of the sixteenth century by which time Shakespeares monster had probably already appeared onstage and the material on which he based his version was certainly well established somebody should have commissioned a portrait that turned out to be so broadly sympathetic. The Richard in the National Portrait Gallery doesnt look like a bad man: he looks like a man with a lot on his mind. The portrait prompted similar reactions in Richards most famous (fictional) advocate, Inspector Grant, hero of Josephine Teys extraordinarily successful pro-Richard detective novel The Daughter of Time (1951). This is, Grant thinks, a painting of Someone too-conscientious. A worrier; perhaps a perfectionist. It is emphatically not an image of villainy. For Grant, the painter, whoever he was, turns out to be on to something, after the policeman has conducted an investigation into Richard from his sickbed. The last words of the novel, spoken by a nurse, are: When you look at it for a little its really quite a nice face isnt it?

What neither the nurse nor Inspector Grant reflect on is that this nice face was as much a work of imagination as any of the nastier faces of Richard made by painters or conjured by chroniclers or playwrights. The National Portrait Gallery painting reminds us that there has very rarely been a settled opinion about Richard III, even in the supposedly propaganda-filled Tudor years. But it also cautions us that all our efforts, like those of the anonymous artist who decided to give back to Richard a little humanity, are prey to some form of wishful thinking. The National Portrait Gallery describes its picture of Richard as using the pattern from an original likeness, and art historians think that the very earliest surviving portrait of Richard, now in the collection of the Society of Antiquaries, was based on one painted from life.remove, at the very least, from Richard himself. There is no contemporary portrait of Richard, no record of his sitting for one. Here, in visual form, is the problem for anyone approaching a life of Richard III. For a king who spent just over two years on the throne, he has received an extraordinary, perhaps even an unsustainable, level of attention and range of opinion. Some of that material was contemporary, but the most powerful, the bits that have stuck in the public imagination longest, like Richards portrait, are not. Reconstructing Richard is often an exercise in admitting our ignorance in stark contrast to the confidence of those who wrote about him shortly after, or even long after, his death and deciding on the balance of probabilities. We can demonstrate how Tudor propaganda or Ricardian advocacy has, in the past, overstated its case, but being sure what isnt right is not the same as knowing what is.

The confirmation that Richards remains had been discovered in Leicester in 2012 offered the hope that in some areas, science could replace speculation about him. But most of the problems with understanding Richard have not been solved by the discovery. These can be summed up as too little to go on, and too much. Too little, because the evidence for Richards life, particularly his life before he became king in 1483, is not exactly super-abundant. He features in royal grants and parliamentary rolls, and is mentioned in near-contemporary chronicles of the period, though the tradition of monastic chronicle-writing was in terminal decline, and the town chronicles that survive are mostly terse records of events, with little embellishment. There are mentions of Richard or things to do with him in the chance survivals of private family correspondence, chiefly that of the Pastons of Norfolk, whose business just happened to overlap with his on occasion. There are a few letters dictated, and fewer lines still actually handwritten, by Richard. The great majority of this material is available in printed editions, of which this book will make copious use. We know about some of Richards own books, though for most of them we cant be sure he read them, let alone what he thought about them. In almost all his earlier appearances on the historical stage, Richard is not the protagonist. As a child he is often invisible, and, even in his formative years as Duke of Gloucester, he is frequently missing from the record. For much of his life we dont know precisely where Richard was at specific times, nor when some very major personal events happened. We dont know, for example, exactly when he got married, nor when his legitimate son or (at least) two illegitimate children were born.

But those gaps are nothing compared to the difficulty of reconstructing Richards personality. Overwhelmingly, the imprint that Richard left on his time was impersonal. It is a record of acquisitions, of political and judicial decisions, of hiring and firing, of public building and foundation, and military planning. The personality that lay behind those acts is thus ripe for speculation. For centuries, Richard has tended to be characterized as a puzzling bundle of contrasts: loyal yet treacherous, pious yet ruthless, courageous yet paranoid. It will be part of the contention of this book that many of these contradictions are more explicable than at first appears. One way of doing that is by trying to stick closely to chronology. The order in which things happened can often go a long way towards explaining why they happened. In the case of Richard, he seems to have been able to adapt to change in an often changeable world. It may seem strange to argue that a man who was killed before he reached his thirty-third birthday was a born survivor, but given the circumstances of his upbringing and the fact that two of his older brothers had died violently, he must have learned to be one. As for the remaining contradictions, they may be due to lack of evidence, or to a Walt Whitman-like multitudinous character. Nobody is consistent throughout their life, and acting in ways that seem to contradict a perceived personality trait is hardly unique. To take an example from Richards own family, his brother, Edward IV, is often characterized (including by contemporaries) as indolent and given to sensuality rather than vigour. Yet he was undoubtedly the greatest military leader of the Wars of the Roses, and despite years of relative peace, was apparently gearing up for a renewed assault on France when he died in 1483. Richard is often categorized, some might say dismissed, as a man of his time. One eminent historian of the Tudors went further, calling him a bore. He lived at the heart of one of the most dramatic periods in English history, and it would be strange if those experiences had not shaped him. But the fact that he could be so unpredictable makes him more than a typical fifteenth-century aristocrat, and very far from boring. Of course, Richard was a man of his time and class. But he was also an individual, and one who has constantly attracted attention over the centuries.

Next page