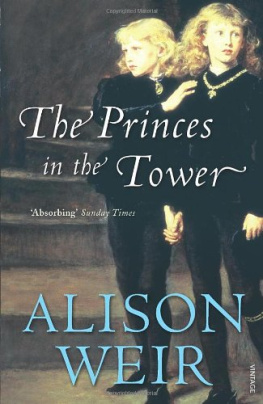

More praise for The Princes in the Tower

Thoughtfully and clearly takes the reader step by step through the arguments and issues.

Chicago Tribune

The Princes in the Tower takes a fresh and illuminating look at one of the great murder mysteries of English history. Alison Weir is a powerful advocate and she marshals her case with skill. The book blends the narrative drive of a novel with the texture of true scholarship. A confident, lively, and thought-provoking book. It has all the elements of a good mysterywith the added bonus of historical fact.

Edward Marston

Author of The Mad Courtesan

Fascinating [A] deeply researched reappraisal of events Readers of this book will care as much about two small boys foully done to death as the identity of their murderer. Detached as a historian should be, Alison Weir still compels speculation about the feelings of Edward V and his brother.

Ruth Rendell

The Daily Telegraph

A carefully researched and absorbing work of scholarship.

Publishers Weekly

A meticulous account of the troubled reign of Richard III.

San Francisco Chronicle

In The Princes in the Tower, Alison Weir examines a case which combines classic mystery, royal scandal, and political intrigue in the court of Richard III. She speaks as eloquently for the prosecution as Daughters of Time did for the defenseand I think Weir has the advantage of being right. It is a fascinating work of scholarly detection, well-written and compelling in its credibility.

Sharyn McCrumb

Author of MacPhersons Lament

With particular lan, Weir reconstructs the tumultuous period For all popular history collections.

Booklist

Good mysteries never die, they just improve with age Weir has assembled an impressive case for the prosecution in The Princes in the Tower.

Orlando Sentinel

A Ballantine Book

Published by The Random House Publishing Group

Copyright 1992 by Alison Weir

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Ballantine and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

www.ballantinebooks.com

Originally published in Great Britain by The Bodley Head in 1992.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 94-96737

eISBN: 978-0-307-80684-0

v3.1

look back with me unto the Tower.

Pity, you ancient stones, those tender babes,

Whom envy hath immured within your walls!

Rough cradle for such little, pretty ones!

Rude, ragged nurse, old sullen playfellow

For tender princes

Richard III, Act IV, Scene I

Ah me, I see the ruin of my House!

The tiger now hath seizd the gentle hind;

Insulting tyranny begins to jet

Upon the innocent and aweless throne:

Welcome destruction, blood and massacre!

I see, as in a map, the end of all.

Richard III, Act II, Scene IV

Contents

Illustrations

Early seventeenth-century (?) copy of a portrait of Richard III. (Courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Ripon Cathedral)

Earliest surviving portrait of Richard, dating from c. 151622. (Society of Antiquaries, London)

The Broken Sword portrait. (Society of Antiquaries, London)

Portrait of Edward IV by an unknown artist, c. 151622. (Society of Antiquaries, London)

Portrait of Elizabeth Wydville in the North Transept Window at Canterbury Cathedral, probably by William Neve between 1475 and 1483.

(Woodmansterne Picture Library)

Illustration from The York Roll by John Rous, c. 14835. (By permission of the British Library)

The Tower of London, from The Poems of Charles of Orlans. (By permission of the British Library)

Copy by an unknown artist of a lost portrait of Henry Tudor of c. 1500.

(Society of Antiquaries, London)

Stained glass window from Little Malvern Priory, Worcester, c. 1481, picturing Elizabeth of York and her sisters.

(Matthew Stevens)

Portrait by Maynard Waynwyk (working 150923) of Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond.

(Courtesy of the Marquess of Salisbury)

Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, from the North Transept Window at Canterbury Cathedral.

(Woodmansterne Picture Library)

Hans Holbeins drawing from life of Sir Thomas More, c. 1527.

(Windsor Castle Royal Library. 1992 Her Majesty the Queen)

Engraving after a painting of the burial of the Princes by James Northcote.

(Guildhall Library, Corporation of London)

Ruins of the Minoresses Convent at Aldgate.

(By permission of the British Library)

Photographs of the remains taken at the time of their exhumation in 1933.

The urn in which the bones repose.

(Courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

The skull of Anne Mowbray.

(Hulton Picture Co.)

Authors Preface

This is a book about the deaths, in tragic circumstances, of two children. It is a tale so rich in drama, intrigue, treason, plots, counterplots, judicial violence, scandal and infanticide, that for more than five centuries it has been recounted and re-interpreted in different ways by dozens of writers. And it is easy to see why: it is a mystery, a moral tale, and above all a gripping story. More compellingly, it is the story of a crime that has never been satisfactorily solved.

There are few people who have not heard of the Princes in the Tower, just as there are few people who do not relish a good murder or mystery story. In the case of the Princes, we have an especially fascinating mystery, not only because they were royal victims who lived in a particularly colourful age, nor because there are plenty of clues as to their fate, but because speculation as to what happened to them has provoked controversy for so many hundreds of years. Even today, the battle still rages between those who believe that the Princes were murdered by their uncle, Richard III, and the revisionists, who have forwarded several attractive theories to the contrary.

It has to be said, at the outset, that it is unlikely that the truth of the matter will ever be confirmed by better evidence than we already have. We are talking about a murder that was committed in the strictest secrecy half a millennium ago in a period for which sources are scanty and often evasive. It is true that documents occasionally come to light which add yet another tiny piece to this extremely complex jigsaw-puzzle, but a historian can rarely hope to produce, in such a case, the kind of evidence that would convince a modern court of law of the identity of the murderer. The historians job is to weigh the evidence available, however slender and circumstantial, and then on a balance of probabilities reconstruct what probably happened. Thus are history books written, and we should not hope for anything better.

For three centuries and more, the revisionist view of Richard III has prevailed, and in recent years the efforts of the Richard III Society have ensured that textbooks are now being cautiously rewritten to present a kinder view of the last Plantagenet king. Yet since the discovery in 1934 of Dominic Mancinis contemporary account of Richard IIIs usurpation, which corroborated many details in the