Pagebreaks of the print version

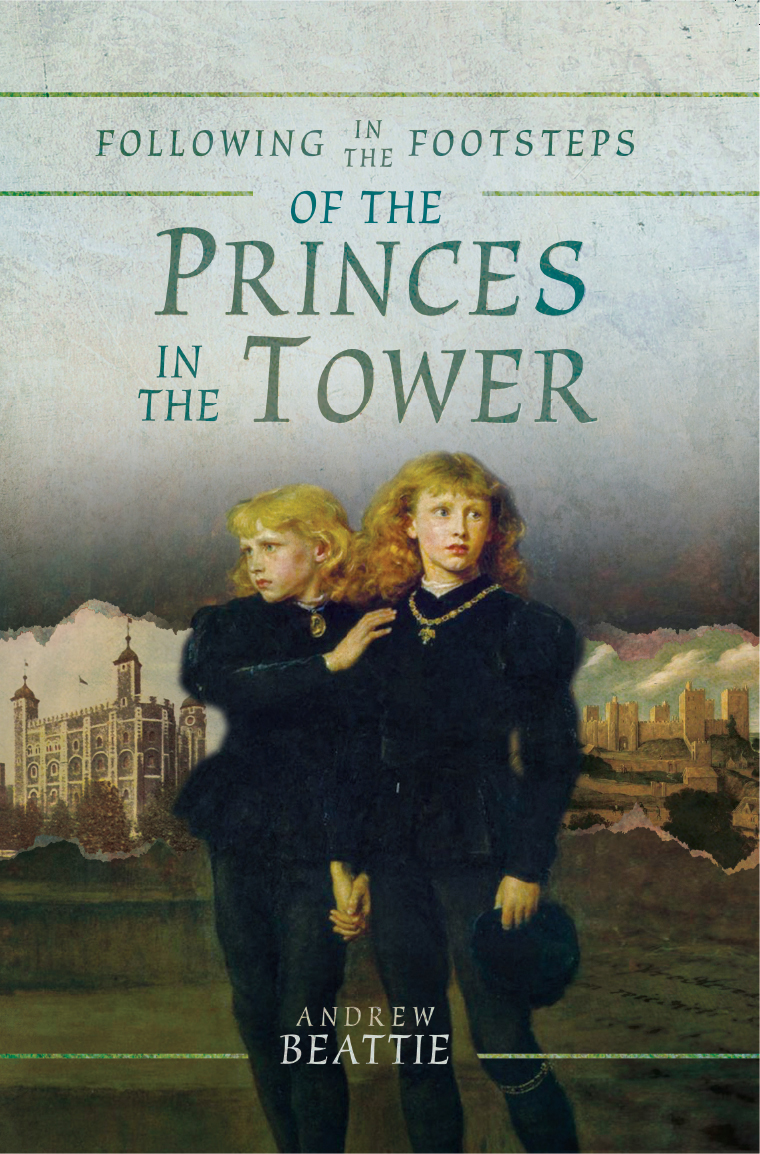

FOLLOWING IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE PRINCES IN THE TOWER

ANDREW BEATTIE

FOLLOWING IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE PRINCES IN THE TOWER

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

Pen and Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Andrew Beattie, 2019

ISBN 978 1 52672 785 5

eISBN 978 1 52672 786 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52672 787 9

The right of Andrew Beattie to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History,

Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime,

Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing,

Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

In The Daughter of Time , the 1951 novel by the celebrated crime and mystery writer Josephine Tey, a cynical, soon-to-be-retired police officer named Alan Grant, recovering in hospital from an operation, decides to use his experience as a criminologist to investigate one of the most notorious supposed crimes in history: whether or not King Richard III was guilty of the murder of his two young nephews, Edward and Richard Plantagenet, the boys known as The Princes in the Tower. He starts off with some detailed reading about the Wars of the Roses, the fifteenth-century civil wars that reached a conclusion soon after the princes disappearance. Grant tried to make head or tail of the wars, Tey tells us, but he failed. Armies marched and counter-marched. York and Lancaster succeeded each other as victors in a bewildering repetition. It was as meaningless as watching a crowd of dodgem cars bumping and whirling at a fair.

In many ways the hapless Inspector Grant was barking up the wrong tree, in his emphasis on the Wars of the Roses as a key to understanding the fate of the princes. Although this long, complex and bloody conflict undoubtedly shaped the events that led to their imprisonment and disappearance, their ultimate fate was the result of a power struggle within one of the warring families the House of York rather than yet another episode of the in-fighting between the rival Houses of York and Lancaster. Inspector Grant really only needed to absorb a brief understanding of the Wars of the Roses to appreciate the historical context to Richard III seizing the throne in 1483 and possibly murdering his nephews.

Such a summary might run something like this: The Wars of the Roses erupted in 1455 as a response to the weak rule of King Henry VI, which revived interest in the rival claims to the throne of a nobleman, Richard, the third Duke of York (the grandfather of the princes in the Tower). The two opposing factions became known as the House of Lancaster (as Henry VI was a descendant of John of Gaunt, the First Duke of Lancaster and the third surviving son of Edward III) and the House of York (as Richard of York was descended from Edmund Langley, first Duke of York, the fourth surviving son of Edward III). Historians also point to the social and financial legacy of the Hundred Years War, which saw many English nobles disaffected by the loss of their holdings in continental Europe, as a contributory cause of the wars.

The conflict dragged on for thirty years. In the opening stages Richard, Duke of Yorks son, Edward, Earl of March, the princes father, defeated and imprisoned Henry VI and was crowned Edward IV. Nine years later in 1470 the situation was reversed when Edward was deposed by Henrys Lancastrian forces. Edward swiftly regained control of the crown from Henry, imprisoned him and possibly ordered his murder, and then ruled until his own somewhat untimely death in 1483. The crisis that engulfed the princes came as a result of arguments concerning Edward IVs will, and who should rule during the minority of his son, Edward V, who acceded to the throne at the age of just 12. Of the two factions Edward IVs widow Elizabeth on one side, and his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester on the other Richard emerged as eventual victor, and was crowned King Richard III, having declared, Edward V and his younger brother Richard by then languishing in the Tower of London barred from the throne as a result of their supposed illegitimacy. Richard IIIs brief rule ended just two years later, when a new Lancastrian claimant, Henry Tudor, defeated him at the Battle of Bosworth Field, which brought the thirty-year conflict to its conclusion. By that time the two princes had disappeared from public view.

Whether they were murdered by Richard III, by his successor Henry VII, or by agents acting for these monarchs with or without their blessing, or whether one or both survived to assume a new identity in adulthood is the subject of many books. But not this one. It is not difficult to see why authors and commentators from the 1480s onwards have attempted to claim (definitively) that they know what happened to the princes: the circumstances surrounding their disappearance remain the most compelling mystery in English history. Alison Weir, whose 1992 book Richard III and the Princes in the Tower firmly pins the blame on Richard III, considers the princes fate to be a tale rich in drama, intrigue, treason, plots, judicial violence, scandal and infanticide a mystery, a moral tale, and above all a gripping story. At the heart of this story is the boy king, Edward V, who reigned more briefly than any English king since the Norman Conquest: just twenty-seven days, from 10 April to 25 June 1483. His coronation was twice postponed and he was never crowned. Although we cannot say anything with certainty about his death, we know much more about him than any other boy of his time. Moreover, he and his younger brother have been cast by history as symbols rather than living, breathing beings. They have been portrayed as innocent lives caught up in a deadly game of power politics, by a host of historians, biographers, playwrights and novelists beginning with Thomas More (Richard IIIs first biographer) and William Shakespeare (whose play Richard III drew heavily from Mores biography).

A survey and discussion of how novelists and playwrights have depicted the lives of the two princes, and have told the story of their imagined fates, is one aim of this book. Moreover, though, this book seeks to look at the princes story in a way that has not been considered before: through the places associated with them during their lives. They were the sons of a reigning monarch and one of them became a monarch himself. Not surprisingly they grew up in castles and palaces and their lives are commemorated in a number of churches. Although some places associated with them are now gone such as the monastery in Shrewsbury where Prince Richard was born, and the Palace of Westminster in London where both of them were brought up, at various stages of their lives many locations survive, most particularly the Tower of London, where they were imprisoned, Ludlow Castle in Shropshire, where Edward Plantagenet spent much of his life, and Westminster Abbey, where a tomb inscribed with their names purports to be their place of burial. Whilst this book does not seek to shed any new or radical light on the princes fate, it is hoped that through accounts of the places associated with them from London and Kent to Shropshire, the English Midlands, and modern-day Belgium a greater understanding of their lives and legacy can be gleaned.