First published in 2014 by

INTERLINK BOOKS

An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc.

46 Crosby Street, Northampton, Massachusetts 01060

www.interlinkbooks.com

Copyright Andrew Beattie, 2014

Cover design by James McDonald | The Impress Group

All photographs Andrew Beattie, except pp. i, x, 56, 114, 140 Wikipedia

Commons; picture section Andrew Beattie and Wikipedia Commons

All rights reserved. The whole of this work, including all text and illustrations, is protected by copyright. No parts of this work may be loaded, stored, manipulated, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information, storage and retrieval system without prior written permission from the publisher, on behalf of the copyright owner.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Beattie, Andrew.

Prague / Andrew Beattie.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56656-956-9

1. Prague (Czech Republic)Description and travel. 2. Prague (Czech Republic)Intellectual life. 3. Prague (Czech Republic)Social life and customs. 4. Prague (Czech RepublicHistory. I. Title.

DB2614.B43 2014

943.712--dc23

2014002406

Printed and bound in the United States of America

To request our 48-page, full-color catalog, please call us toll free at 1-800-238-LINK, visit our website: www.interlinkbooks.com, or send us an email: info@interlinkbooks.com

Contents

Geography, Myth, and Growth

Libue and the Legend of Pragues Foundation

What Really Happened: The History of Prague to 1000 AD

The Capital of the Czech Republic

Development and History

The View from Charles Bridge

Early Days

Connections

Buildings and Styles

Medieval Architecture

Renaissance Prague

Baroque Churches

More Baroque: Synagogues, Statues, Palaces, and Gardens

The Nineteenth Century

Art Nouveau

St. Vitus Cathedral

Cubism, Functionalism, and Modernism

Post-War Architecture

A Brief Social and Political History

Medieval Prague (850-1378): The City Established

Jan Hus and the Czech Reformation (1378-1419)

Religious Strife (1419-1526)

Habsburg Prague (1526-1918)

Democracy and Occupation (1918-45)

Under Stalins Gaze (1945-68)

The Prague Spring and the Velvet Revolution (1968-89)

Prague since the Velvet Revolution

Prague in Literature

The First Thousand Years

Kafka in Prague

Kafkas Contemporaries

The Communist Era

Vclav Havel and the Samizdat Tradition

British and American Views

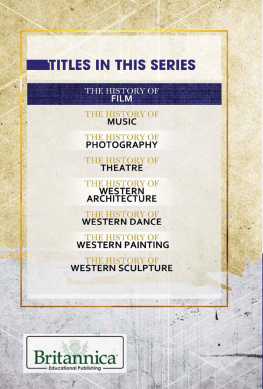

The Visual and Performing Arts

Painting, Sculpture, Photography, and Design

Film

Music

Popular Culture and Pastimes

Escape to the Country

May Day and Christmas

A Day Out

An Afternoon in the Park

An Evening in the Pub

The Religious Landscape

Christian Prague

Judaism, Islam, and Eastern Religions

Saints and Martyrs

Migration and Social Change

The Roma Community

The Vietnamese

Trade and Consumerism

The Middle Ages: Merchants and Markets

From Tuzex to Tesco

Trade Fairs

Murder, Madness, and Persecution

Magicians and Alchemists

The Jewish Community

The Holocaust in Prague

The Heydrich Assassination and the Tragedy of Lidice

The End of Nazi Rule

Communist Prague

The Cemeteries

Todays Hidden City

The Hinterland

Castles, Countryside and Spa Towns

North of Prague: the Elbe

Kutn Hora

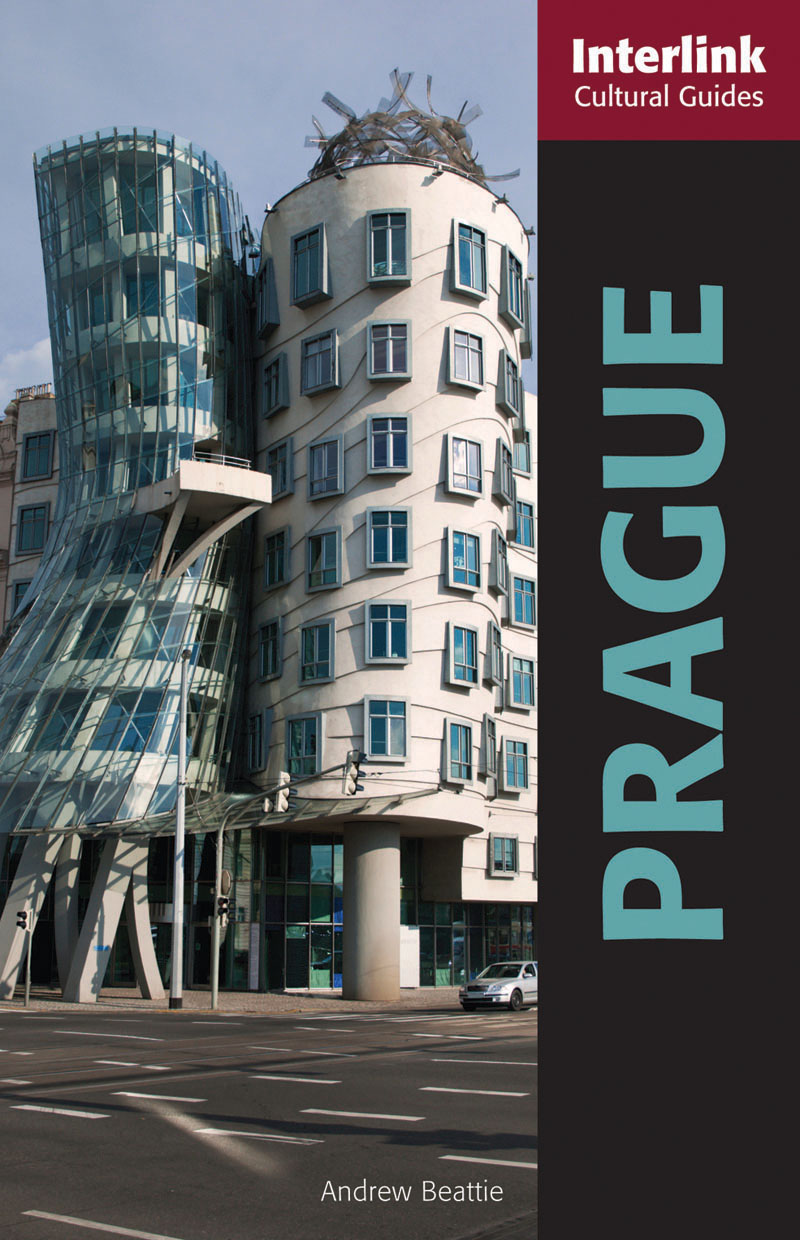

I n 1591 the artist Johannes Putsch created a remarkable allegorical map of Europe. It portrayed the continent as a reclining empress, with Hispania as her head, Italy, and Denmark as her arms, and Bohemia as her heart. Putsch depicted Bohemia by means of a multitude of spires that represented the city of Prague. At that timethe late sixteenth centuryPrague was one of the greatest centers of Renaissance learning in Europe, thanks to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II acting as patron to an extraordinarily diverse group of artists and scientists who flocked to his magnificent court. History was to prove Rudolf to be one of the citys most remarkable rulers. But he was not the instigator of Pragues greatness. By Rudolf s time the city had been a vital metropolis for over five centuries, flourishing on the trade that passed along the River Vltava and on the silver that was mined nearby in Kutn Hora.

Along with this greatness, however, there was a dark and mystical side to the city, of which Johannes Putsch would have been well aware. It was made apparent by the legends of the Jewish Quarter and by the alchemists whom Rudolf II attached to his court, and in ensuing centuries Pragues dark side revealed itself to have a political dimension too, as the struggle for independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire bizarrely saw three defenestrations the throwing of individuals out of windowsdefine the citys destiny. Yet throughout centuries of turbulence Pragues medieval and Baroque heart remained gloriously intact, undiminished by war or by the rapid suburban growth that came later on with the industrial revolution. By the turn of the twentieth century the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, swept up by the drama of the ancient skyline, was still able to describe the city as a golden ship sailing majestically on the Vltava, while Franz Kafka, the citys most famous literary offspring, wrote in a letter to his friend Oskar Pollack in 1902 that Prague does not let go, either of you or of me. This little mother has claws. There is nothing for it but to give in. The writer and journalist Egon Erwin Kisch, Kafkas contemporary, was of a similar mindset. Prague is magic, something that ties you down and holds you and always brings you back, he wrote. You can never forget it.

The remarkable allegorical map of Europe created by Johannes Putsch in 1591, portraying the continent as a reclining empress with Bohemia as her heart

On the first floor of the City of Prague Museum, located on the outskirts of central Prague, beside the main bus station, visitors peer through glass at a vast model of the city that spreads luxuriously across a single room. The model is fashioned from cardboard and was the work of an early nineteenth-century artist named Antonn Langweil, who took over twenty years to painstakingly construct his masterpiece. Every detail is clear, from the ornate decorations on the Renaissance houses in the Old Town Square to the curving buttresses on St. Vitus Cathedral. What is remarkable about the model is how little in Prague has changed in the two hundred years since Langweil began work on it. The cathedral has been completed (its entire western portion dates entirely from the 1870s) and the Jewish Quarter has been remodeled, but in the model, Prague looks substantially as it does today: a Baroque city occupying a medieval ground plan, with distinctive neighborhoods and a castle overlooking it all from a spectacular eyrie above the river. No wonder that since the era of the models construction the city has drawn writers and tourists in their droves. Even in communist times the place was a magnet for visitors: in her 1968 book Your Guide to Czechoslovakia, Nina Nelson wrote that there was a branch of edok, the Czechoslovak state tourist agency, on Oxford Street in London, and that edok agents could sell tourists a two-week bus tour of Czechoslovakia (including flights) for just 77. That was the year, of course, when political affairs in the country made headlines all around the world, as Warsaw Pact forces intervened to crush the reform movement known as the Prague Spring. In those days tourists were relatively few in number (and most came from East Germany). But since the coming of democracy in 1990 Prague has earned a reputation for being one of the great tourist cities of the world, with tour groups clogging the major squares and thoroughfares throughout the year.