E LIZABETH

W OODVILLE

Four things come not back:

The spoken word;

The sped arrow;

Times past;

The neglected opportunity

Old Saying

E LIZABETH

W OODVILLE

Mother of the Princes in the Tower

D AVID B ALDWIN

First published in 2002

This edition published in 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL 5 2 QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

David Baldwin, 2002, 2004, 2010, 2011

The right of David Baldwin, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6897 6

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6898 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

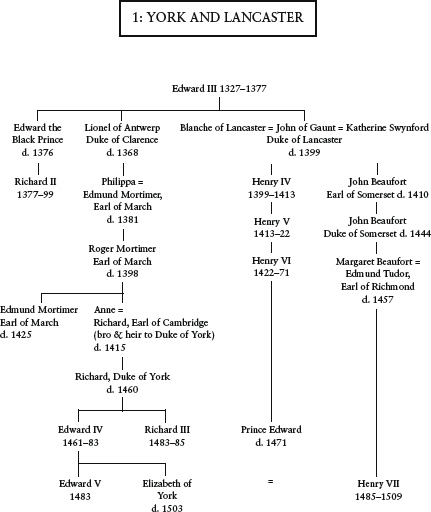

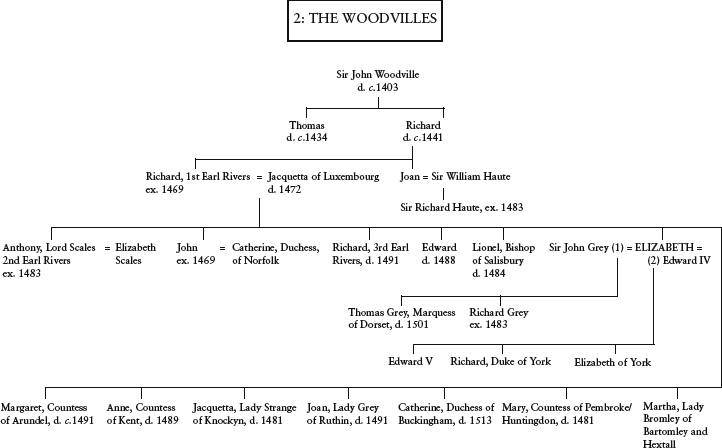

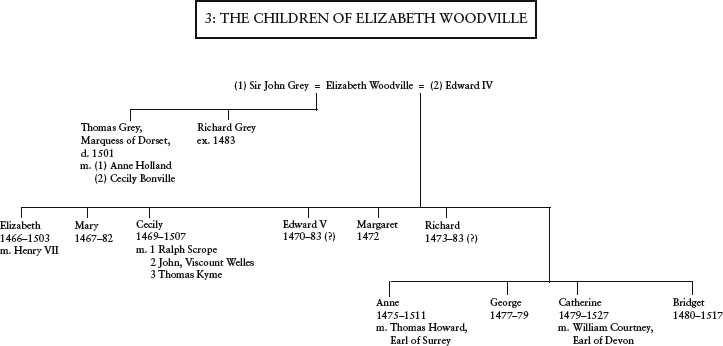

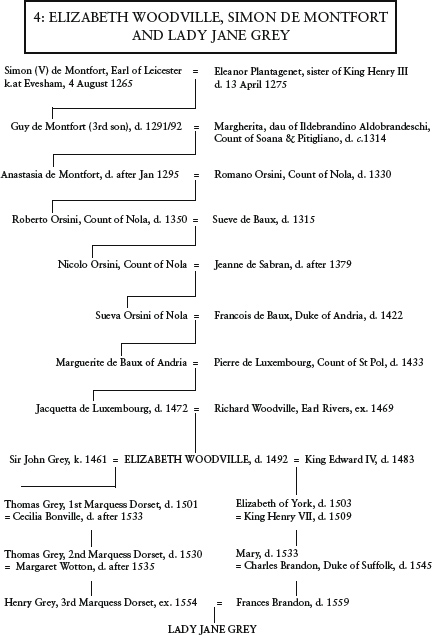

Genealogical Tables

Introduction

E lizabeth Woodville spent her earliest years in relative obscurity at Grafton Regis in rural Northamptonshire, but she was destined to become the wife of King Edward IV, mother of Edward V, sister-in-law of Richard III, mother-inlaw of Henry VII and grandmother of Henry VIII. The eldest of the twelve children which Jacquetta, dowager Duchess of Bedford bore her second husband, the middling county knight Sir Richard Woodville, she was to experience more vicissitudes of fortune than the heroine of any novel or television soap opera. Her legendary meeting with Edward IV beneath the oak tree at Grafton and their secret marriage baffled contemporaries and led to allegations of witchcraft; her husbands promotion of her relatives bred resentment among the older noble families and contributed to her spending two fearful phases of the Wars of the Roses in sanctuary; her father, two of her brothers, and a son from her first marriage were executed and the Princes in the Tower, her sons by King Edward, disappeared mysteriously; and the last five years of her life were spent in religious seclusion after a plot to depose Henry VII misfired. But her reign as queen was not all tribulations. There were royal progresses, great state occasions and tournaments, the satisfaction of interceding with her husband on behalf of plaintiffs, of influencing his policies behind the scenes and fulfilling the role of a great lady on her own estates. She has been praised and vilified (more often the latter) by both contemporaries and later writers, but few have tried to understand her difficulties, to probe her mind (to plumb her unfathomable relationship with Richard III, for example), or answer the question What was she really like?.

Some prospective biographers may have been dissuaded from studying Elizabeth by a vague, and possibly erroneous, notion that it would be difficult to bring their work to a satisfactory conclusion. It is sometimes said that it is all but impossible to write the life of a medieval man or woman because the detailed, personal information needed to understand their motives and actions is not available. Only seldom are there memoirs by contemporaries who knew their subject, and almost never a substantial body of correspondence between friends or family. The dry mass of chronicles and administrative records may tell us what a person did or received or suffered but not what he or she thought or hoped for; and there has been a tendency to produce books which describe themselves as the Life and Times of the subject (with much space and emphasis given to the Times) or alternatively, to resort to an unacceptable amount of speculation in order to create a real, thinking individual. Informed guesswork is probably essential, but when overused can result in caricature bearing only passing resemblance to the person concerned.

These difficulties apply to Elizabeth as much as they apply to her contemporaries, but the lack of some evidence and of absolute certainty does not render a conventional biography impossible. Much material has survived, and if it does not always tell us all that we would like to know it still provides the basis for a reasoned assessment. I have tried to tell the story of her life as accurately as possible, resorting to conjecture only when her involvement is distinctly likely: few kings, or chroniclers writing on their behalf, would openly declare they acted upon their wifes suggestion or recommendation, although there must have been many occasions on which queens obtained favours or directly influenced policy.

My intention has been to provide enough background information to make Elizabeths career intelligible to readers who have little or no previous knowledge of the late fifteenth century, but not to make her an excuse for another general book on the Wars of the Roses. Accordingly, the events of the reign of Edward IV, her second husband, are discussed only insofar as she influenced or was affected by them. I have tried to let contemporary documents tell their own story, wherever possible, rather than interpret them to conform to a preconceived view of her character, and have found little to substantiate the conventional portrait of the haughty queen and her grasping family. Certainly her relatives were ambitious, but Warwick, Hastings, Clarence and Gloucester the men with whom they clashed so bitterly never themselves refused a grant or declined an opportunity, and the modern view of them is essentially that created by Warwicks propaganda in 1469 and Gloucesters of 1483.

Elizabeth is a fascinating but neglected character there have been three biographies of her Lancastrian rival, Margaret of Anjou, in English since the Second World War and much new material has come to light since the publication of David MacGibbons Life in 1938. Historians will continue to argue about some of the episodes of Elizabeths career for example, her part in the Simnel conspiracy but she was, I believe, one of the most politically aware, and, at the same time, judicious, Queen Consorts, who fulfilled her difficult role as competently as anyone before or since. My over-riding concern has been would Elizabeth Woodville recognise herself in these pages? I hope and I think that she would.

On a practical note I have tried to distinguish carefully between the several John Pastons, the various Margarets, and Elizabeths two sons named Richard (to give but three examples) and to refer to noblemen principally by their titles rather than by their lesser-known personal names. The footnotes are designed primarily to acknowledge quotations and sources of evidence and to enlarge upon and justify interpretations; I have not, generally speaking, given references for facts which are accepted and uncontroversial and have only provided such information where, as it seemed to me, a question might arise from the main text.