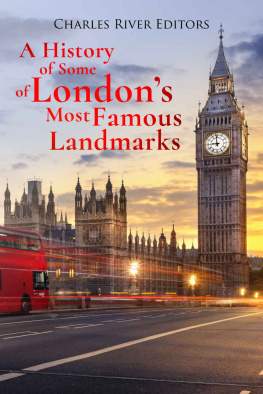

The Tower of London is one of the most familiar symbols of British power and history. Even its shape is compelling: the strong, impenetrable, square mass of the central keep; the White Tower, with its circular turrets at the four corners surrounded by gray walls, bastions, lesser towers, and a moat on three sides; on the fourth, bordering the Thames, sits the Tower Wharf.

Built by William the Conqueror in 1078, the Tower is an ever-present reminder of the Normans and their conquest of England. To act as his surveyor and superintendent, William selected a former Norman monk, Gundulf, whom he appointed Bishop of Rochester, to build the White Tower, the first structure within the existing Roman walls. William built his first fortress in the southeast angle of the wall; subsequently, the Wardrobe Tower was erected on the base of a Roman bastion.

The Tower was not simply a fortress. It was at various times a royal palace, a prison, the home of the Royal Mint, the treasury for the Crown Jewels, a repository for state papers, and an observatory. Since the lion was considered a suitable gift for kings and queens, one tower - the Lion Tower - was a menagerie. As other animals accumulated bears, leopards, lynxes, and wolves - the Tower became (until 1834) the original London Zoo.

After it received its girdle of walls and subsidiary towers and was surrounded by a deep moat excavated by the lion-hearted Richard I, the exterior of the Tower looked much like it does today. But inside, significant changes were made. In front of the White Tower on the south side facing the river, a royal palace was erected. Here, many historic events took place - stately and ceremonial, pathetic and dreadful - such as the murder of King Edward IVs young sons. It was customary for kings and queens to spend the night or a few days in these apartments before their coronations at Westminster. Charles II was the last to follow this tradition; after him, the royal lodgings fell into disuse and were ultimately abandoned.

Still, the complex of buildings known collectively as the Tower of London offers a unique trinity: fortress, palace, and prison. France had its Bastille and Rome its Mamertine for a state prison; Spains El Escorial was both royal palace and monastery; the popes had their Castel SantAngelo, but the Tower of London combined all these functions. The Royal Commission on Historical Monuments describes it as the most valuable monument of medieval military architecture surviving in England. It is in the Tower buildings that the history of England is revealed.

Today, observers view the Tower as a revered relic of the past, a slice of ancient history preserved for posterity. But watching the tide lap the wharf outside Traitors Gate, seeing the mist rise from the river like a shroud, the ancient history comes alive with ghostly memories.

Second to William the Conqueror, the king who left the greatest mark on the Tower was Henry III, who also built Westminster Abbey. By 1236, he had reconstructed the Great Hall, the Wakefield Tower, next to the royal lodgings, the archway to the Bloody Tower, and the main angle towers along the wall. The devout king had the Norman chapel of St. John in the White Tower redecorated, and he refurbished the Church of St. Peter ad Vincula, painting the royal stalls, recoloring the images and figures, erecting a new statue of the Virgin in the north aisle, adding panels before the two altars, and commissioning the sculpting of a marble font. He had his own chamber in the royal lodgings frescoed, as in the papal palace at Avignon. Henry III was anxious to keep up with his French relations: Like all medieval kings till the end of the Middle Ages, he was a Frenchman.

Henry had trouble making a direct waterway entrance from the Thames into the Tower: The foundations of the wharf would not hold. Not until 1275, when Edward I built the Tower of St. Thomas were the foundations finally secured. In Tudor times, the Water Gate beneath St. Thomass Tower became better known as Traitors Gate - a troublesome sign of the times. All that remained for Henry VIII to add were two large mounts for his more modern cannons, the Kings House or Lieutenants Lodging in the southwest corner, and the angle-turrets on the White Tower.

The Tower was the stage of some of the significant events of Richard IIs reign, from his coronation to his abdication. At the outbreak of the Peasants Revolt in the summer of 1381, Richard, with his Court and ministers, took refuge in the Tower, where they watched London burn. Unsure of what to do, the young king took the initiative and sent a message to Mayor Walworth to meet him at Mile End. In the morning, Richard met the rebels to hear their demands.

The Tower was well-guarded by men-at-arms and archers, and the Court should have been safe. Inside were the kings mother, the beautiful Joan of Kent, the archbishop of Canterbury, Treasurer Robert Hales - responsible for the poll-tax that had incited the peasants to revolt - and other lords and ministers. While the king was away at Mile End, the mob burst in and dragged the archbishop and the treasurer from the chapel, where they had taken refuge, and with two others, executed them on Tower Hill. The kings mother was smuggled out of the Tower to Baynards Castle, while her son dealt with the rebellious peasants.

In his later years, Richard, psychotic and unstable, made a hopeless king, and the ruling class, in alliance with the Church, turned against him. In 1399, while cloistered in the Tower, Richard was forced to abdicate. He did not resign the Crown voluntarily, nor did he resign it to his cousin, Henry IV, but to God. There, within the Tower walls, the chief justices were instructed to make the formal renunciation of homage and allegiance to the dethroned monarch.

Henry IV would probably not have attained the throne if Richard II had been fit to rule. Likewise, the House of Lancaster would have held the throne if Henry VI had been sane. The contest for the throne resulted in the Wars of the Roses a series of conflicts fought between supporters of two rival branches of the Royal House of Plantagenet, the House of Lancaster, and the House of York. More than anything else, the trading classes of London wanted an efficient and stable government, which King Henry could never provide.

The country, the Church, and most of the peerage stood with the accredited royal house. Even with Henrys debility, the issue was only decided in favor of the Yorkists because of the military prowess of young Edward IV. In the ensuing Wars of the Roses, the Tower played a significant role - as a refuge for the military, a prison to hold traitorous inmates, and a stage for historical melodrama.

Out of the changes of 1459-61, Edward of York emerged victorious at the Battle of Towton, fought on Palm Sunday in a snowstorm. The defeat was fatal for the Lancastrians. Many of their leaders were killed, though the indomitable Queen Margaret safely carried Henry and their son, the Prince of Wales, into Scotland. Edward came south for his coronation on Sunday, June 29, 1461. A couple of days before, he was accompanied to the Tower by the mayor, aldermen, and citizens, enthusiastic at the prospect of peace and order. Edward feasted his Yorkist lords and partisans and created thirty-two Knights of the Bath, who rode before him in the customary procession to Westminster.

Edward IV used the Tower as a residence more than any king before him. This was partly for its military convenience and partly because of the instability of his throne during his first decade; another reason was its proximity to the city, where he was careful to cultivate popularity. Ceremonies and celebrations at the Tower were particularly grand in 1465 when Edward married the Lancastrian widow Elizabeth Woodville.