JEREMIAH TOWERS

RECIPES, MEMORIES & MENUS

FLAVORS

OF TASTE

WITH KIT WOHL PHOTOGRAPHY SAM HANNA

INTRODUCTION

When I saw in 2016 that Anthony Bourdain claimed Jeremiah Tower was the guy who transformed American menus from what they were to what they are now, it occurred to me I should write a book to tell that story. Hes the history of everything. Its all there. Its a great story.

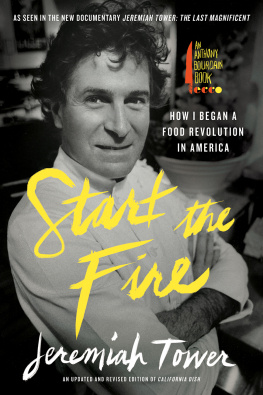

After starting the book that became (April 2017) Start the Fire: How I Began a Food Revolution in America, I realized I had already told some of the story in 1986 with my James Beard Foundation Award winning Best American Regional Cookbook, Jeremiah Towers New American Classics. But perhaps it was time for a tune up, and to update the cookbook. When my good friends and fellow writers Linda Ellerbee suggested and Kit Wohl insisted, we did. With Flavors of Taste.

In the 20 years since New American Classics, several new and at the time astonishing things about it have now become every day stuff. Just as when the latest fashion fad of Madonnas leather bras by Jean-Paul Gaultier had stopped shocking the fashionista world, in came Molecular Gastronomy to shake up the foodie culinary world.

Chef Jacques Pepin: Molecular gastronomy is like Jean-Paul Gaultier coming down the runway. You ask yourself who would wear that, but eventually it trickles down to become prt-a-porter, or what you wear every day. And that is how classics happen, the things that trickle down and stick, not just because of popular assent, but because they fit.

Where the everyday comes from is the point of this book. In May 2016 one of the many Facebook fans of Classics, Zach Engel (a brilliant chef in New Orleans) posted: If youre a cook read this and then go read his books and then his cookbooks. Because knowing where we came from helps us to move to where we need to be. Back to the future. Looking back to see the way ahead.

I try to teach cooks about who our predecessors are because they are the ones who have given us the opportunities to shine in a modern age of cuisine, Zach says.

In other words, whichever new and brilliant approaches to food, ingredients, and cooking are introduced, the kick start for the new thinking comes from the original benchmarks.

I have broken up the original book into a series, of which this is the first. And since we are now at another critical tipping point, if not revolution, all include newer and more recipes.

The original Personal Favorites has been expanded to include some favorite classical moments in food and eating, as well as some recent benchmark moments of my own.

If youre a cook read this and then go read his books and then his cookbooks. Because knowing where we came from helps us to move to where we need to be. Back to the future. Looking back to see the way ahead. - Chef Zach Engel

PREFACE

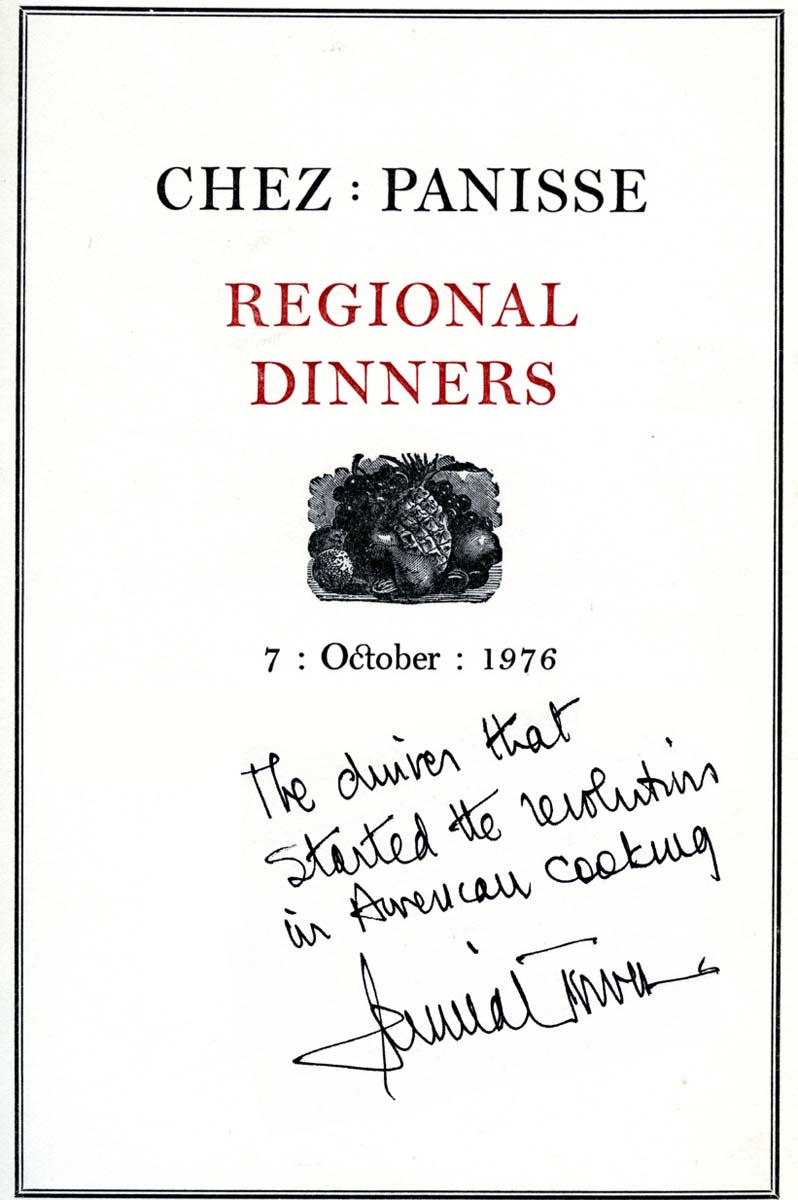

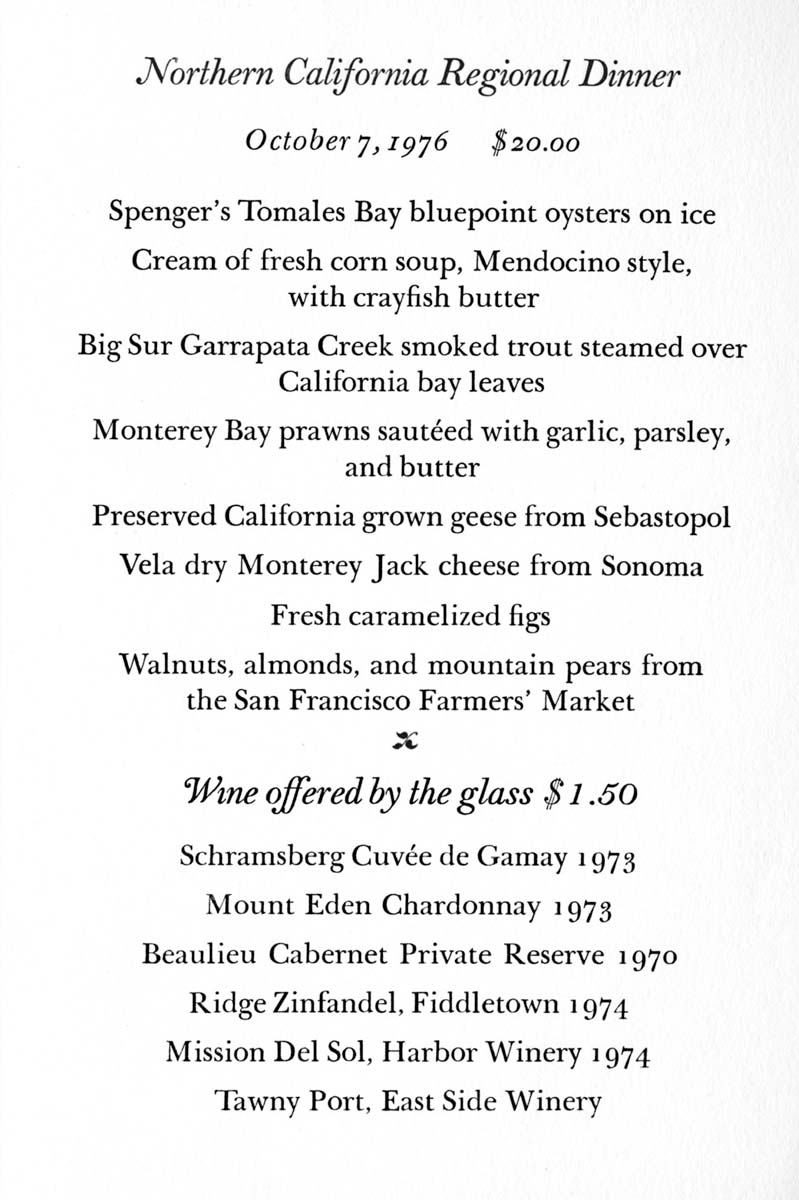

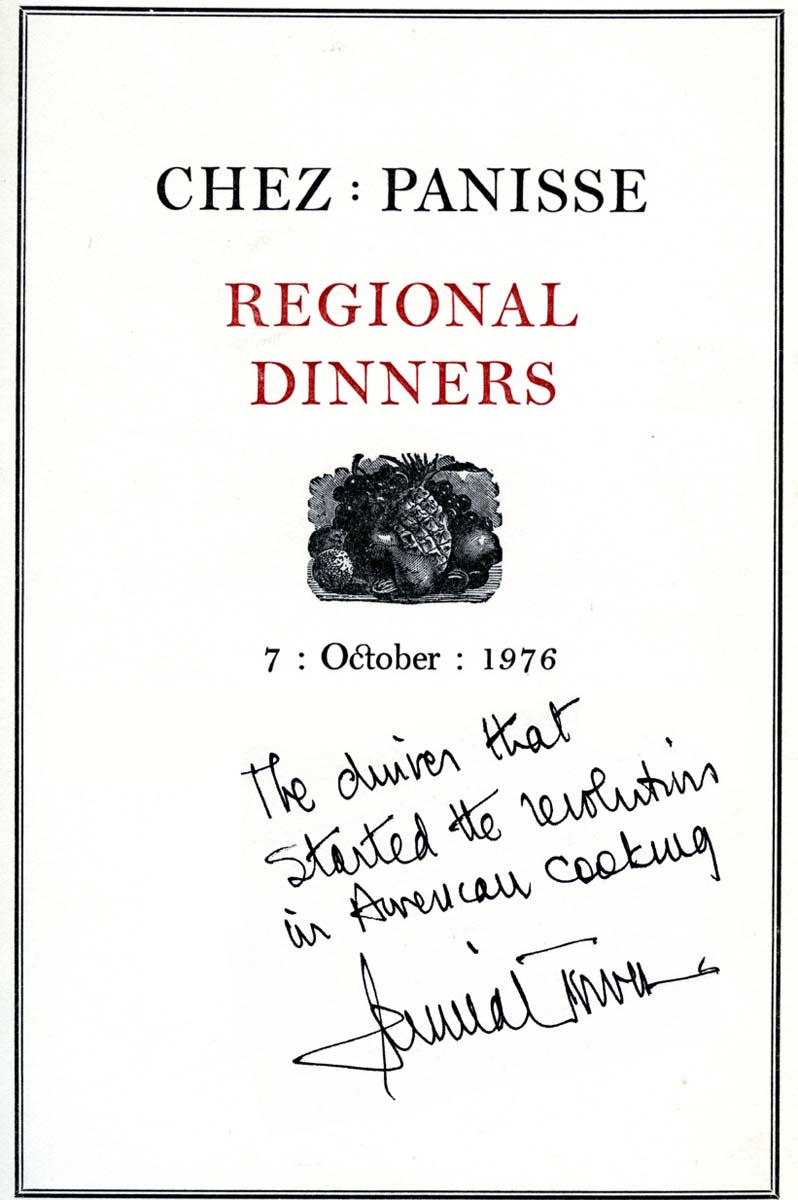

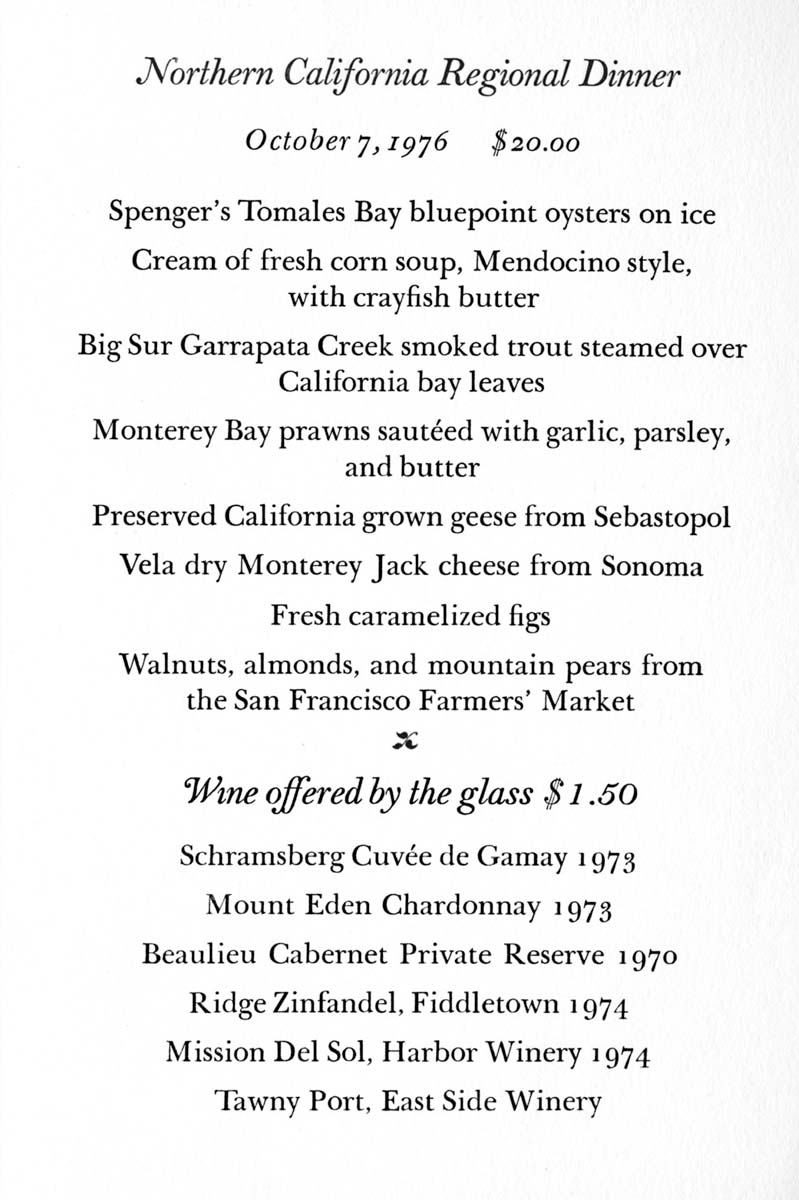

I started my professional cooking career in 1972 as chef of Chez Panisse restaurant in Berkeley, California. After two years, I had landed on my feet and, looking around for ways to challenge the restaurant, I started a series of special monthly dinners, each featuring a menu from a region of France.

After two years, most of Frances regions had been used up, I turned to Morocco, and finally to Corsica, though with great difficulty in finding anything Corsican that anyone wanted to eat. In those days Chez Panisse was a French country bistro, if with the stirrings of the unborn California movement.

One morning when the restaurant was closed, I was reading The Epicurean, a Franco-American Culinary Encyclopedia by Charles Ranhoffer, which contains recipes used at Delmonicos in New York from 1862 to 1894. Under soups I saw Crme de mais verte la MendocinoCream of green corn la Mendocino.

What struck me about the recipe was that it took its name from a town up the coast from San Francisco. What, I wondered, were chefs in New York in the 1890s doing thinking about Mendocino? And did they really name ingredient locations way back then?

Like a bolt out of the heavens, the realization came to me: why am I scratching around in Corsica when I have all around me the bounty of California? I looked further into the chapter on soups and saw the words Cambridge and Portland, and next to Dubarry and Svign I saw Franklin and Livingstone. We used to live in General Livingstones house in Brooklyn Heights, and could the Franklin be Benjamin?

The recipe for the green corn soup was breathtaking in its simplicity, elegance, and informality. Take fresh young corn, cook it briefly, mash it to a pure, add broth, sieve it, reheat almost to a boil, add an egg yolk and cream liaison to thicken the soup and, at the moment before serving, whisk in a fine crayfish butter.

The soup was garnished with cooked shrimp tails cut in small pieces. I immediately revised the recipe, using less crayfish butter in the soup and swirling a crayfish cream over the top.

It was American food using French cooking principles. I could not contain my exhilaration as I felt the enormous doors of habit swing open onto a whole new vista.

I began to compose an American regional dinnerCalifornia, not Corsica.

The oysters were harvested the morning of the dinner, as was the corn, though the crayfish came from Big Sur the day before and were kept alive in a kitchen sink overnight.

The prawns were driven up from the Monterey Bay where a dishwasher had spent the night in a motel so as to be at the docks at 6 a.m. The geese I had bought as goslings several months before, and they had been raised in Sonoma by a rancher friend and then preserved by me a month before the dinner.

All the wines were chosen to promote local California wineries, and the Harbor Mission del Sol was from a garage in Emeryville next to the Bay.

The restaurant and Iand several otherswere never the same again. I put the menus in English and gave up the regions of France, except for inspiration in how pure a regional cooking should be.

Since then I have gone on professionally through Ventana in Big Sur, the Balboa Caf in San Francisco, the Santa Fe Bar and Grill, and Stars San Francisco to develop a style of cooking which, in its influence and scope, drawing on bar and grill, bistro, brasserie, and classical restaurant food, has become a new American classic.

Here are some inspirations from the past that steady me in the present and lead me into the future.

It was American food using French cooking principles. I could not contain my exhilaration as I felt the enormous doors of habit swing open onto a whole new vista.

I began to compose an American regional dinnerCalifornia, not Corsica.

PERSONAL FAVORITES

I read Elizabeth Davids French Provincial Cooking in 1970 and was enthralled and totally inspired by the essays at the front of the section called The Cooking of the French Provinces. Among them Mrs. David offers a description, in her own words, of Escoffiers Shooting Weekend Fifty Years Ago, translated from a 1912 issue of his monthly magazine published between 1911 and 1914 called Le Carnet dEpicure (A Gourmets Notebook).

Next page