Copyright 2004 by Robert Lacey

Illustrations and maps 2004 by Fred van Deelen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First published in Great Britain by Little, Brown and Company, 2004 First United States edition, June 2005

First eBook Edition: November 2009

ISBN: 978-0-316-09039-1

ROBERT, EARL OF ESSEX

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF HENRY VIII

THE QUEENS OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC

SIR WALTER RALEGH

MAJESTY: ELIZABETH II AND THE HOUSE OF WINDSOR

THE KINGDOM

PRINCESS

ARISTOCRATS

FORD: THE MEN AND THE MACHINE

GOD BLESS HER!

LITTLE MAN

GRACE

SOTHEBYS: BIDDING FOR CLASS

THE YEAR 1000

THE QUEEN MOTHERS CENTURY

ROYAL:HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II

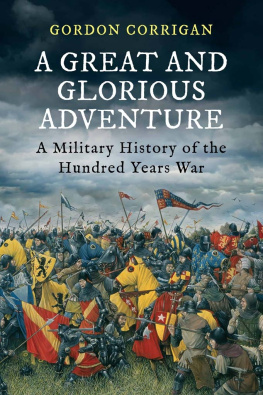

GREAT TALES FROM ENGLISH HISTORY:

THE TRUTH ABOUT KING ARTHUR, LADY GODIVA,

RICHARD THE LIONHEART, AND MORE

FOR SCARLETT

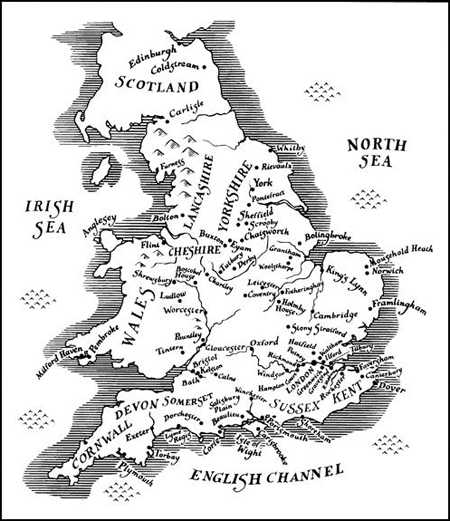

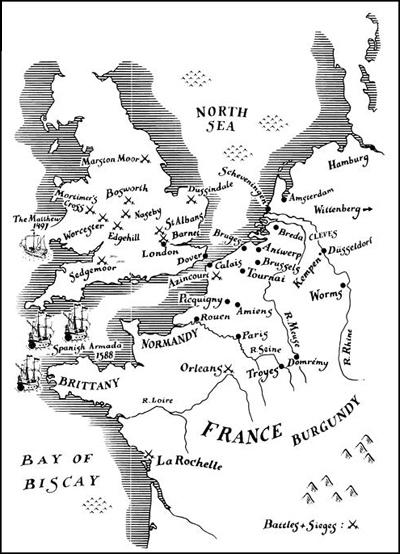

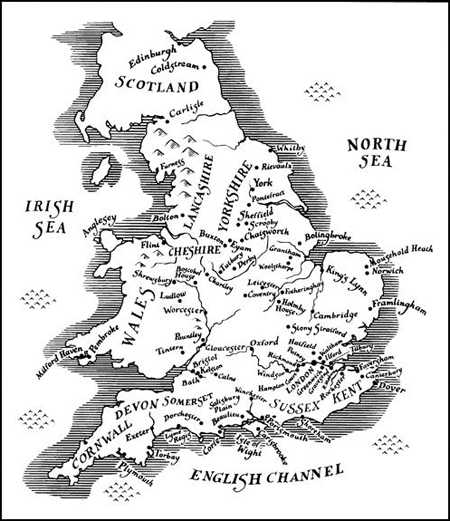

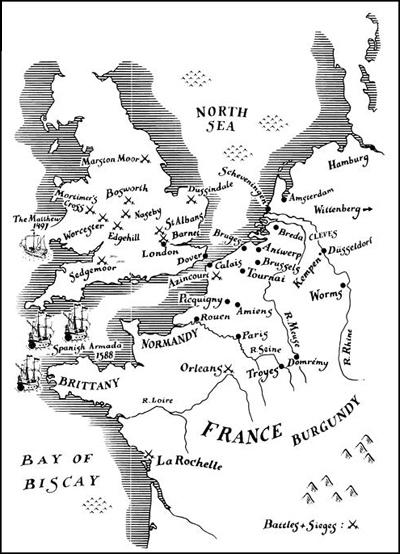

(see map on for battles)

F OR MOST OF US, THE HISTORY IN OUR HEADS is a colourful and chaotic kaleidoscope of images Sir Walter Ralegh laying down his cloak in the puddle, Isaac Newton watching the apple fall, Geoffrey Chaucer setting off for Canterbury with his fellow pilgrims in the dappled medieval sunshine. We are not always sure if the stories embodied by these images are entirely true or if, in some cases, they are true at all. But they contain a truth, and their narrative power is the secret of their survival over the centuries. You will find these images in the pages that follow just as colourful as you remember, I hope, but also closer to the available facts, with the connections between them just a little less chaotic.

Our very first historians were storytellers our best historians still are and in many languagesstory andhistory remain the same word. Our brains are wired to make sense of the world through narrative what came first and what came next and once we know the sequence, we can start to work out the how and why. We peer down the kaleidoscope in order to enjoy the sparkling fragments, but as we turn it we also look for the reassuring discipline of pattern. We seek to make sense of the scanty remnants of the lives that preceded ours on the planet.

The lessons we derive from history inevitably resonate with our own code of values. When we go back to the past in search of heroes and heroines, we are looking for personalities to inspire and comfort us, to confirm our view of how things should be. That is why every generation needs to rewrite its history, and if you are a cynic you may conclude that a nations history is simply its own deluded and self-serving view of its past.

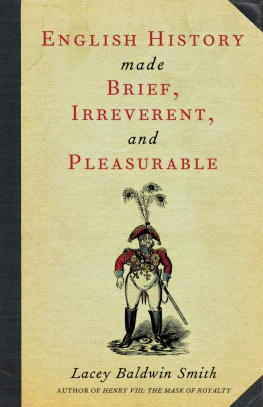

Great Tales from English History is not cynical: it is written by an eternal optimist albeit one who views the evidence with a sceptical eye. In these books I have endeavoured to do more than just retell the old stories; I have tried to test the accuracy of each tale against the latest research and historical thinking, and to set them in a sequence from which meaning can emerge.

The first volume of Great Tales from English History showed how the beginnings of English history were shaped and reshaped by invasion Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Danish, Norman. And that was just the armies. The Venerable Bede, our first English historian, described the invasion of the new religion, which, in AD 597, so scared King Ethelbert of Kent that he insisted on meeting the Christian missionaries out of doors, lest he be trapped by their alien magic. We met Richard the Lionheart, Englands French-speaking hero-king, who spent only six months living in England and adopted our Turkish-born patron saint, St George, while he was fighting the Crusades. Then, as now, we discovered, some of the things that most define England have come from abroad. Magna Carta was written in Latin, and Parliament, our nationaltalking-place, derives its name from the French.

This volume opens in the aftermath of another invasion by a black rat with an infected flea upon its back. In 1348 and in a succession of subsequent outbreaks, the Black Death wiped out nearly half of Englands five million people. Could a society undergo a more ghastly trauma? Yet there were dividends from that disaster: a smaller workforce meant higher wages; fewer purchasers per acre brought property prices down. In 1381 the leaders of the so-calledPeasants Revolt with which we concluded the earlier volume were men of a certain substance. They were taxpayers, the solid, middling folk who have been the backbone of all the profound revolutions of history. Later in this volume we will see their descendants enlisting in an army that would behead a king.

Changing economic circumstances have a way of shaping beliefs, and so it was in the fourteenth century. John Wycliffe told the survivors of plague-stricken England that they should seek a more direct relationship with their God, read His word in their own language, and not rely upon the priest. Wycliffes persecuted followers, the Lollards, ormumblers, as they were called by their detractors, in derision of their privately mouthed prayers, would provide a persistent underground presence in the century and a half that followed. If invasion was the theme of the previous volume, dissent spiritual, personal and, in due course, political will take centre stage in the pages that follow.

Sir Walter Ralegh, one of the heroes of this volume and one of mine is said to have given up writing his History of the World when he looked out of his cell in the Tower of London one day and saw two men arguing in the courtyard. Try as he might, he could not work out what they were quarrelling about: he could not hear them; could only see their angry gestures. So there and then he abandoned his ambitious historical enterprise, concluding that you can never establish the full truth about anything.

In this sobering realisation, Sir Walter was displaying unusual humility both in himself and as a member of the historical fraternity: the things we do not know about history far outnumber those that we do. But the fragments that survive are precious and bright. They offer us glimpses of drama, humour, frustration, humanity, the banal and the extraordinary the stuff of life. There are still a good few tales to tell

Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote