Table of Contents

ALSO BY ROBERT LACEY

Robert, Earl of Essex

Henry VIII

The Queens of the North Atlantic

Sir Walter Ralegh

Majesty

The Kingdom

Princess

Aristocrats

Ford

God Bless Her!

Little Man

Grace

Sothebys

The Year 1000

The Queen Mothers Century

Monarch: The Life and Reign of Queen Elizabeth II

Great Tales from English History: Cheddar Man to the Peasants Revolt

Great Tales from English History: Chaucer to the Glorious Revolution

Great Tales from English History: The Battle of the Boyne to DNA

To Faiza, Fawzia, Ghada, Hala, Hatoon, Maha, Najat,

and all the mothers of Saudi Arabia

And to the memory of my own mother,

Vida Lacey (1913 -2008)

PREFACE

Welcome to the Kingdom

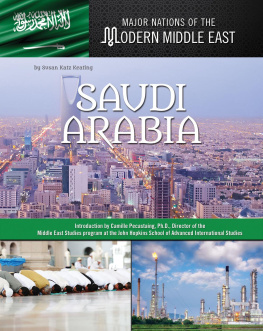

In theory Saudi Arabia should not existits survival defies the laws of logic and history. Look at its princely rulers, dressed in funny clothes, trusting in God rather than man, and running their oil-rich country on principles that most of the world has abandoned with relief. Shops are closed for prayer five times a day, executions take place in the streetand let us not even get started on the status of women. Saudi Arabia is one of the planets enduringand, for some, quite offensiveenigmas: which is why, three decades ago, I went to live there for a bit.

It was 1979. I had just published Majesty, my biography of Elizabeth II, which recounted the paradoxical flourishing of an ancient monarchy in an increasingly populist world. Now I was in search of more paradox, and it was not hard to find in Riyadh. After many a morning sipping glasses of sweet tea in the office of the chief of protocol, I finally secured an audience with King Khaled, the shy and fragile old monarch who had become the Kingdoms stopgap ruler following the assassination of his half brother Faisal in 1975. (The five Saudi monarchs who have ruled the Kingdom since 1953 have all been half brothers, with more than a dozen brothers and half brothers, not to mention their sons, still waiting in the wingssee the family tree on page xxiv.)

In the weeks of tea sipping I had given much thought to the important question of what I might give the king. What could I offer to the man who hador could havejust about anything? I had decided on photographs. Before coming to the Kingdom, I had read the papers of the earliest British travelers to Arabia, intrepid servants of His Majestys imperial government who had trekked across the desert sands in the early decades of the twentieth century in their solar helmets and khaki puttees. A surprising number had loaded their camels with the heavy wood-and-brass cameras of the time, complete with fragile glass plates and portable darkrooms so they could develop and print their negatives in their tents.

I made up an album of these images, which were then comparatively unknown, wrote out long captions and had them translated into classical Arabic, and bore my gift into the royal presence. It was majlis daymajlis meaning the place of sittingand the bedouin had come out of the desert to sit with their king. Inside the manicured palace grounds were dusty Toyota pickup trucks parked higgledy-piggledy on the marble among the burnished Rolls-Royces and BMWs of princes and ministers. The trucks did not have sheep or goats in the back at that moment, but from their smell it was clear they had recently contained some woolly passengers.

I was already prepared for the theater that followed. The nose rubbing and hand kissing as the king met his people was a tableau unrolled for every visiting film crew and journalistour desert democracy, the minders from the Ministry of Information would proudly explain. Till that date I had managed to avoid a ministry minder (thirty years later I still proudly roam free), and I was developing my own rather cynical view of desert democracy. It seemed to me to involve little more than the passing thrill of royal contact, the handing out of money, and the dispensing of favors that bypassed and undermined the fragile processes of proper government. So I was 50 percent skeptical as I entered the majlisthen 100 percent bowled over as I found myself treated to some direct royal contact of my own.

In front of the king was standing an old bedu, his bare toes scratching nervously at the rich silken carpet as he declaimed singsong lines of poetry, which he seemed to be making up as he went along:

Oh love of the people,

Oh Khaled, our king,

Oh lion of the desert,

Your promises we sing...

Listening to poetry is one of the occupational hazards of being king of Saudi Arabia. Elizabeth II shakes hands with a lot of district nurses. Saudi kings must nod appreciatively through the repetitive and often lengthy odes composed in their honor. In the meantime, there was a flurry of robed and shuffling hospitality, as thimblefuls of thin coffee got poured and trays of clear, sweet tea were circulated. The Riyadh equivalent of Buckingham Palace flunkeys were stern-looking, cross-belted retainers, wearing revolver holsters and swords.

Suddenly it was my turn to entertain the king, and I found myself ushered with my gift to the green brocade overstuffed sofa beside himLouis Farouk is the decorative style favored in most Saudi palaces, a mixed allusion to the excesses of Versailles and the last, gaudy king of Egypt.

It was sticky to start with. How many times had this shy, long-suffering man had to accept the homage of stumbling foreigners? But as he turned the pages of the album, King Khaled started to get it. He recognized uncles and cousins and places from long ago, and, above all, the pictures of his extraordinary, charismatic father, Abdul Aziz, Slave of the Mightythe mighty one being God, whom Abdul Aziz served devotedly through the creed that outsiders call Wahhabism, central Arabias harsh and fiercely puritannical interpretation of the Islamic faith. Usually known in the west as Ibn Saud, or Son of Saud, this warrior king had subdued and pulled together the tribes of Arabia between 1901 and 1925, then proudly (some said arrogantly) slapped his family name on the whole bundled-up conglomerate: Al-Mamlaka Al-Arabiyya Al-Saudiyya, the Saudi Arab KingdomArabia as belonging to the House of Saud.

The great mans son Khaled was now turning the pages of my album with real interest, calling over cronies to look at such and such a face or to question whether such and such a caption was correct about the date or placeuntil he came to a photo dated 1918. It showed Abdul Aziz standing smiling and self-assured in a headdress and winter cloak, almost a head taller than a line of rather less confident relatives and companions, while a group of ragged little children in the front row squinted quizzically at the first European that most of them had ever seen. (See photo insert facing page .)