Also by Michael Jones

The Kings Mother

Agincourt 1415: A Battlefield Guide

Stalingrad: How the Red Army Triumphed

Leningrad: State of Siege

The Retreat: Hitlers First Defeat

Total War: From Stalingrad to Berlin

The Kings Grave: The Search for Richard III

BOSWORTH

Pegasus Books LLC

80 Broad Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10004

Copyright 2015 by Michael Jones

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition September 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part

without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may

quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or

electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written

permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-60598-859-7

ISBN 978-1-605-98860-3 (e-book)

Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

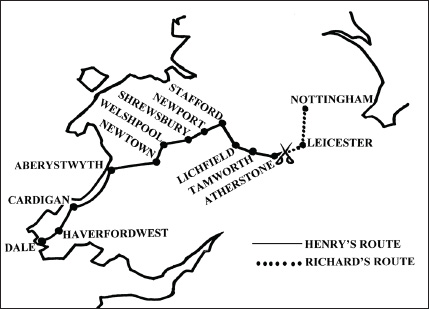

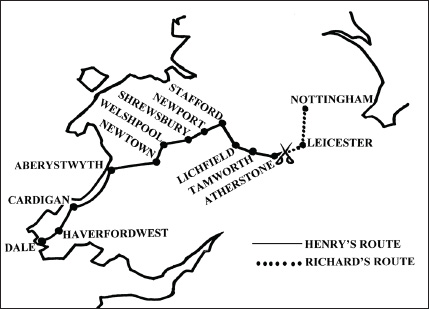

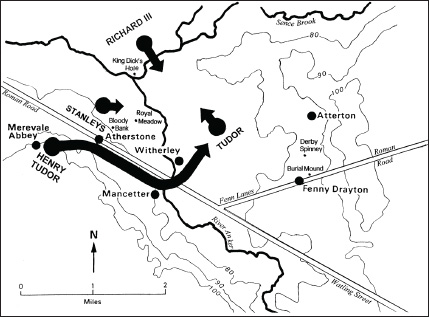

The approach routes of the two armies. The redating of Tudors advance by Griffiths and Thomas, in 1985, showed he progressed more slowly than had been thought. In this revised chronology, Henry only enters England at Shrewsbury on 17 August, two days later than commonly accepted. Tudor was pressed for time in the last phase of his march. This factor becomes significant when we consider the alternative battle site, eight miles further west. In this scenario, Henry would have less distance to cover.

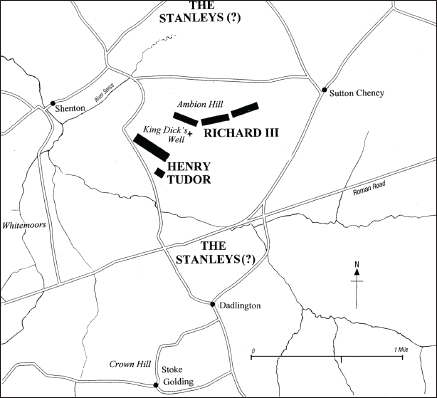

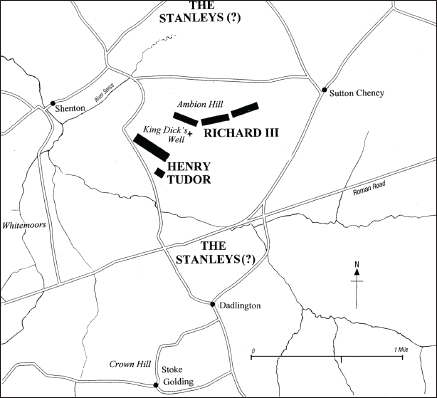

The traditional battle site, with Richard III on Ambion Hill and Henry Tudor approaching from the west. The flanking manoeuvre described by Polydore Vergil is almost impossible to achieve and the position of the Stanleys unknowable. The name King Dicks Well dates from the late eighteenth century.

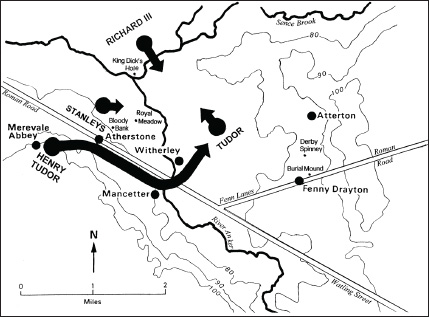

The proposed alternative battle site. The map shows (i) the possible start positions of the rival armies on the morning of 22 August 1485; (ii) Henry Tudors flanking manoeuvre and final deployment; (iii) the position of the Stanley forces in Atherstone, mid-way between the two armies; (iv) the parishes named in Henry VIIs compensation grant (Mancetter, Witherley, Atterton and Fenny Drayton). The clusters of place-name evidence might suggest the clash of the vanguards took place north of Atherstone, in the vicinity of Royal Meadow and Bloody Bank, and that Richards engagement with Tudor occurred further east, with the fighting spilling into the parishes of Fenny Drayton and Atterton, and culminating close to Derby Spinney and the burial mound. (Modern roads have been omitted).

O n my twelfth birthday, I saw Sir Laurence Oliviers film version of Richard III. I was fascinated by the eerie horror of its culmination: the battle scenes at Bosworth. As an undergraduate at Bristol University the whole period was brought alive for me by my tutor. Professor Charles Ross encouraged my enthusiasm for the late Middle Ages and I wrote one of my first essays for him on that battle. Now, some twenty-five years later, I can make a response of my own to his inspiration. This book is a product of much adult research. But it has been germinated by something simpler: the love of history I had as a child and the compelling power of its stories. So it is a story I offer here, and a quite sensational one. Whether in an academic sense it is true or not is not ultimately important. This tale needs to be told.

The book is based on considerable scholarship but is quite deliberately intended for the general reader. Names, dates and factual detail are kept to a minimum, particularly in the early chapters of the book, to allow the story to gather momentum. The sources on which this story is based are introduced gradually. It is footnoted, but relatively lightly, and contains maps, a timeline and a family tree for easy reference.

I acknowledge many debts in writing this book. Most are mentioned in the footnotes. Here I would like to thank the British Academy, which provided funds for the research undertaken in France, and Carolyn Hammond, the librarian of the Richard III Society for her kindness and help when I carried out my work. Professors Tony Pollard and John Gillingham have read through the text and Tony has kindly contributed the foreword. Drs Jonathan Hughes and Carole Rawcliffe have also commented on an earlier draft. To all I am grateful for their suggestions. As we say in the trade, the responsibility for what remains lies solely with me. Geoffrey Wheeler has undertaken the picture research in a way which I believe really enhances the text. And my wife Liz has not only lived with the book, but her feedback has made it a better one. It was written whilst our son Edmund was in his first year and it is dedicated to both of them.

M ore than ten years have passed since the first edition of this book, and in the interval our understanding of Bosworth and the king who fought and died there has moved forward substantially. In the last few years significant archaeological discoveries have taken place. Major finds of artillery shot and other remains including a boar badge, the personal emblem of Richard III, probably worn by one of his supporters in the last fateful cavalry charge against his opponent give us a clearer idea of the battles location and, movingly, where the king may have met his end. And the remarkable discovery of Richards remains under a car park in Leicester show the terrible injuries he sustained in that clashs bloody denouement.

History is about tangibility and we now have a far greater connection to Richard III and Bosworth. When I wrote the book, in 2002, Richards battle position was still a matter of debate. Now battlefield archaeology has placed the king further east than I originally suggested, blocking the Roman road to Leicester a mile and a half to the west of Dadlington, although Henry Tudor and his army almost certainly marched to meet him from the abbey of Merevale, as I proposed. Our grasp of this fateful clash has progressed, and when Richards remains were dramatically unearthed in the summer of 2012 we saw the wounds that ended his life: the kings head was shaved by a glancing blow from a sword and the back of his skull cleaved off by a halberd a two-handed pole weapon, consisting of an axe blade tipped in a spike.

However, other aspects of the battle remain more elusive. While the crucial importance of the French mercenaries in Henry Tudors army is clear, the tactical arrangement that made them so effective is less so. In 2002 I suggested that some of these troops were deployed in a pike formation to protect Tudor from Richards cavalry charge. The evidence here is indirect but nevertheless compelling. Tudors French soldiers had been largely recruited from a disbanded war camp at Pont-de-lArche in eastern Normandy. These troops had been drilled and trained in pike weaponry, and by 1484 their elite group, the francs-archers, had been converted to this form of deployment. I still think it likely that this formation was used against Richard at Bosworth, in the clash of vanguards, and also to protect Tudor when the kings cavalry charge came so close to killing his opponent and winning the battle.

Next page