T HE L AST W HITE R OSE

DESMOND SEWARD

Constable London

For Tim and Marisa Orchard

Table of Contents

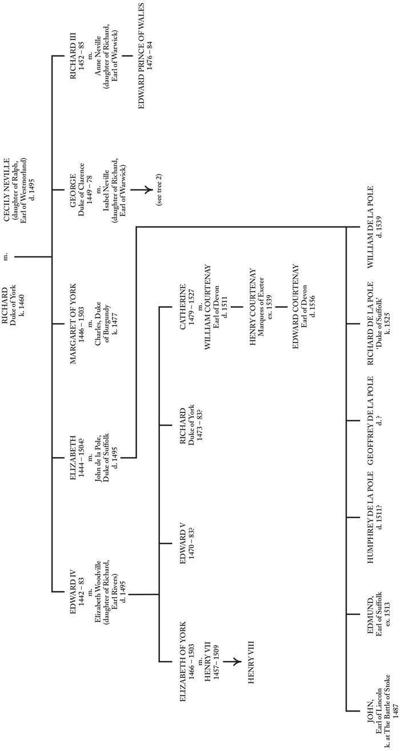

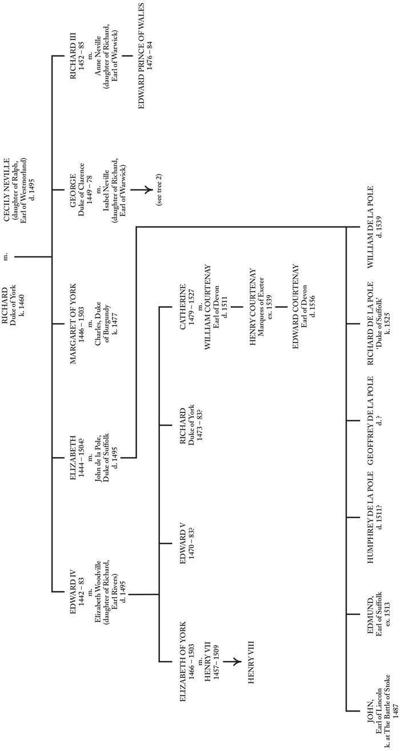

1. The Royal Descent of the de la Poles and the Courtenays

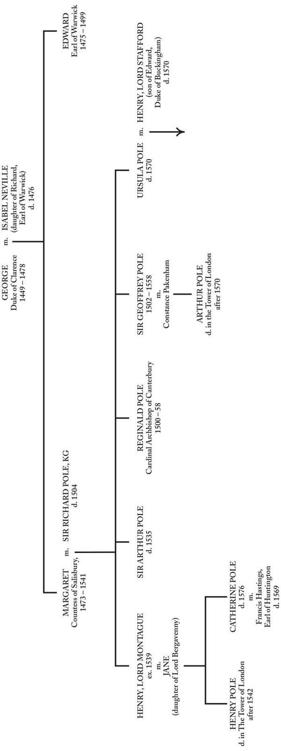

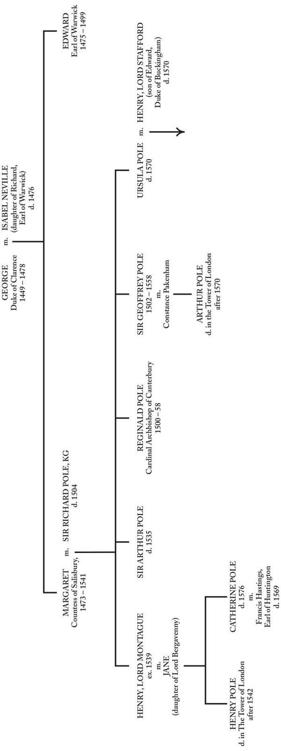

2. The Royal Descent of the Poles

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Fifteen years ago I published a book called The Wars of the Roses and the Lives of Five Men and Women in the Fifteenth Century (Constable, 1995). This is the sequel, telling the story of what happened to the Yorkists in the decades after the battle of Bosworth and the death of Richard III and why they so alarmed Henry VII and Henry VIII.

Once again, I owe much to the patient staffs of the British Library and the London Library. I am most grateful to my agent Andrew Lownie, to my editor Leo Hollis and copy-editor Elizabeth Stone, and to Sara Ayad for reading the proofs. I have to acknowledge two special debts one to Sir John Hervey-Bathurst for reading my typescript and for helpful comments at every stage, the other to Richard Despard, who let me have access to his unpublished researches on the families of Foix-Candale and de la Pole. I must also thank Lucia Simpson for her sterling encouragement.

Overview: The White Rose, 14851547

The White Rose is most trueThis garden to rule by rightwise law.The Lily White Rose methought I saw. The Lily White Rose, c.1500

At Bosworth on 22 August 1485, at the head of his Knights and Squires of the Body, Richard III charged down on Henry Tudors puny army in the field below. Killing Henrys standard-bearer, Richard hacked his way towards him the two may even have exchanged blows. At the very last moment one of the kings followers, Sir William Stanley, changed sides in the battle. Galloping across the field with 3,000 troops, he annihilated Richard and the royal household. Henry owed his life and his throne to treachery.

As Shakespeare imagines the scene, after the battle Sir Williams brother Lord Stanley offers the dead kings crown to Henry with the words, Wear it, enjoy it and make much

Henrys campaign had been a desperate gamble. Most of his followers were ex-Yorkists, outraged by Richards seizure of the throne, who supported him only because no other pretender was available. His claim to be king (through his mother, last member of a bastard branch of Lancaster) was far from convincing, even if he was crowned at Westminster Abbey by the same Archbishop of Canterbury who had crowned Richard III only two years earlier and even if Parliament had passed an Act recognizing him as king. For all his high words about his just title, it was in fact as shaky as could be without being non-existent. This is a good description of Henrys position in 1485. Thereafter, most revolts which he faced were similar pieces of high politicking about which family to put on the throne. His policy was to murder or neutralise as many likely rivals as possible, a policy which his son took up in mid life.

There was still a Plantagenet heir after Bosworth and many Englishmen were uneasy about replacing a dynasty that had ruled for over 300 years. 1486 saw a rising in support of Richard IIIs young nephew Edward, Earl of Warwick, while the following year Lord Lincoln led a revolt in the earls name, using a boy called Lambert Simnel to impersonate him. During the 1490s the Tudors were threatened by Perkin Warbeck, who, encouraged by the Yorkist underground, posed as one of the Princes in the Tower and called himself the White Rose. Indeed, there were so many plots against the Tudor king that a court poet compared the first twelve years of his reign to the Labours of Hercules.

Early in 1499 an astrologers warning of yet more danger from the Yorkists caused Henry VII to suffer a complete nervous collapse, and a Spanish envoy reported that he had aged twenty years in a fortnight. Shortly afterwards, he decided to kill Warwick, the last male Plantagenet. Unluckily for the king, the earls legal murder gave rise to the widespread rumour that his execution had brought a curse on the Tudors, dooming their male children to an early death. In any case Yorkism persisted as a belief that there were men with a much better right to represent the Plantagenets than this new, self-invented royal family and another White Rose soon emerged to claim the throne.

Another title for this book could have been The Shadow of Richard III. As a boy Henry VIII must have known that if his father died, his line would probably disappear: as a king without a male heir, he became convinced that his own death would mean the end of the Tudors. When eventually he did father a son, he feared that if he died too soon the child might go the same way as Edward V. That is why anyone with Plantagenet blood lived under a death sentence, no English king having sent so many men or women to the scaffold. These, and many other such deaths, were a testimony to the profound disquiet that haunted Henry throughout his life, comments Lucy Wooding. It was a direct inheritance from his father.

Henry VIIIs disquiet first showed itself in 1513. When about to invade France he had Edmund de la Pole executed, to prevent him from being proclaimed king in his absence, while for the next decade Tudor agents tried to murder Richard de la Pole, Edmunds successor as the White Rose. Although Richard, the last man to challenge Henry VIII openly for the throne, was killed at Pavia in 1525 when fighting for the French, the king grew increasingly suspicious of any nobleman with Yorkist blood. Revealingly, the Treason Act of 1534 denounced as traitors those who wrote or said he was a usurper of the crown.

During the early1530s England was rocked by Henry VIIIs divorce from Katherine of Aragon and the Churchs break from Rome, and by new laws that increased the powers of the crown. No one disliked the changes more than Katherines supporters, who included the White Rose party, by now centred around two families, the Courtenays and the Poles. The head of the Courtenays, the Marquess of Exeter, was a grandson of King Edward IV. The Poles, headed by Lord Montague, consisted of the four sons of Margaret Plantagenet, Countess of Salisbury (sister of the Earl of Warwick who had been Richard IIIs heir). They hoped to replace Henry with his daughter Mary, with Reginald Pole as a Yorkist king consort, and their ally Bishop Fisher implored the imperial ambassador to ask Charles V to come and overthrow Henry VIII, whom he claimed was even more unpopular than Richard. But the revolt never took place as the plotters lacked a leader.

In 1536 a rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace broke out in Lincolnshire, and then in Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumberland, with 30,000 men demanding an end to religious innovations and the dismissal of Cromwell and Archbishop Cranmer. The king tricked them into dispersing, before taking a savage revenge. This was the most dangerous moment of Henry VIIIs reign and had it come to a fight he might easily have been toppled. But the White Rose families made the fatal mistake of sitting on the fence.

Next year Pope Paul IV appointed Reginald Pole to lead a mission to force Henry VIII to bring England back to Rome or depose him. Pole hoped to revive the Pilgrimage of Grace, but was too late. In 1539 he led another unsuccessful mission, to persuade Charles V to invade England. Henrys reaction was to exterminate the White Rose families and their supporters, send assassins to kill Pole and execute his mother, the Countess of Salisbury the last living Plantagenet. Even then, the king did not feel secure, destroying the Howards because he feared they would try and take the throne from his young son.

Next page