Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR

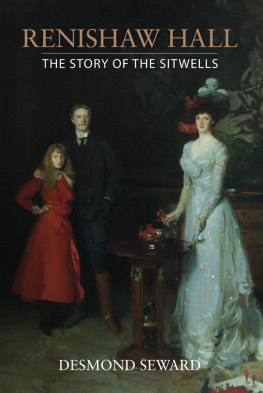

Desmond Seward was born in Paris and educated at Cambridge University. He is the author of Richard III: Englands Black Legend, The Monks of War, and The Wars of the Roses.

For my godsons

Mark Kendall

Tobias Riley-Smith

Paul Seward

Acknowledgements

My first debt is to two Benedictine monks, Dom Marcel Pierrot and Dom Jean Bequet of Ligug, who took me over the battlefield of Poitiers sixteen years ago. I am sincerely grateful to them for starting my interest in the Hundred Years War, and to their monastery for its memorable hospitality.

I am especially indebted to Mr Reresby Sitwell for much encouragement, for many useful ideas, and for reading the typescript and the proofs; to Mrs Prudence Fay for her invaluable editorial criticisms; to Sir Iain Moncreiffe of that Ilk for the suggestion that Charles VIs madness may have been caused by porphyria; and to Commander W. F. Patterson, RN(Retd), Chairman of the Society of Archer-Antiquaries, for the diagrams of the long-bow and crossbow and for advice on the technical points of medieval bowmanship.

Among those who gave me information about the part played by their families in the Hundred Years War were Lord Mowbray, Segrave and Stourton, Lord Dunboyne and the Hon Nicholas Assheton. Lord Mowbray supplied me with material about the life of his ancestor the first Lord Stourton, who had an unusually profitable career during the later stages of the War, Lord Dunboyne provided me with details about the Butlers and other Irishmen in France, while Mr Assheton drew my attention to Sir John Assheton who served with Henry V in Normandy.

I must also thank Mr Michael Thomas, Mr Christopher Manning, Mr Hubert Witheford and Mr David Beynon, and Miss Mollie Luther who helped find the illustrations.

Finally I would like to express my gratitude to Mr Richard Bancroft of the British Library, to Mr Esmond Warner, the Honorary Librarian of Brookss, and to Miss E. V. Baird and Miss E. A. Hollingdale of Brighton Library.

Foreword

Do you not know that I live by war and that peace would be my undoing?

Sir John Hawkwood

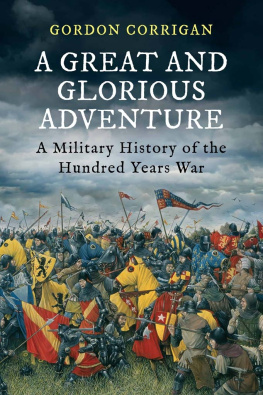

This is a short, narrative account of the Hundred Years War for the general reader. Other studies have either been translated from the French, and dismiss Agincourt in a few lines, or are too scholarly. However, while this book is not for the specialist, it nevertheless makes full use of the recent research which has radically altered the traditional picture of the War.

The phrase The Hundred Years War only gained currency during the late nineteenth century. In fact it gathers together a series of wars which lasted longer than a hundred years. They are generally assumed to have begun in 1337 when Philip VI of France confiscated the English-held Duchy of Guyenne from Edward III, who then claimed the French throne, and to have ended in 1453 when the English finally lost Bordeaux. For most of the period England enjoyed a remarkable military superiority thanks to the fire-power of the long-bow.

Some of the battles are part of the English legend, like the glorious victories of Crcy, Poitiers and Agincourt, but there are also the little known (to Englishmen) defeats at the end when French cannon routed their once invincible archers. The protagonists are among the most colourful in English and French history: Edward III, the Black Prince, and the even more formidable Henry V; the splendid but inept John II who died a prisoner in London, the sickly, limping intellectual Charles V, who very nearly overcame the English, and the enigmatic Charles VII (Joan of Arcs Dauphin) who at last drove them out. The supporting English cast included such men as Sir John Chandos, John of Gaunt, the Duke of Bedford and Old Talbot, as well as Sir John Fastolfthe original of Shakespeares Falstaff. On the French side were figures like the Constable du Guesclin, the Bastard of Orleans and the witch-saint from Domrmy.

While the chronicler Froissart paints a pageant of glittering court life, a Bourgeois of Paris tells of times when wolves entered Paris to eat the corpses. The world of the Trs Riches Heures du Duc de Berry was as bloody as it was beautiful. For the French, unlike the English, the War was more than a mere saga of battles; it was a dreadful experience, which like modern warfare, involved the entire community.

For over a century one Western country systematically plundered another. A distinguished modern historian has written that the contemporary English attitude to the War was as a speculative, but at best hugely profitable, trade that was shared by all who joined the mercenary armies of Edward III and Henry V ... He adds that by 1450 among those who had done best out of the war were the great landed families, while as for needy adventurers of obscure birth and no inherited property; scores of them made notable fortunes. Indeed generations of Englishmen of every class went to France to seek their fortunes, in rather the same way that their descendants would one day go to India or Africa. Of course there were other incentives besides greed, as anyone who has read Froissart or King Henry V will realizeknight-errantry, feudal loyalty or a primitive patriotism. If the emphasis on material motives in this book may sometimes seem excessive, it is partly because their role has been underestimated in popular accounts of the Hundred Years War; and partly because recent research has given us much more information about the extent and nature of spoils won in France and how they were spent in England.

Whatever the motives, a sustainedand, on the whole, extraordinarily successfuloffensive was waged for over a century by a poor and scantily populated little country against a richer, more populous and ostensibly far more powerful enemy. It is arguable that the Hundred Years War was medieval Englands greatest achievement.

Valois or Plantagenet? 13281340

Dare he command a fealty in me?

Tell him the Crown that he usurps is mine,

And where he sets his foot he ought to kneel.

Tis not a petty Dukedom that I claim,

But all the whole dominions of the realm;

Which if with grudging he refuse to yield

Ill take away those borrowed plumes of his

And send him naked to the wilderness.

The Raigne of King Edward III

Sir, does it not seem to you that the silken thread encompassing France is broken?

Sir Geoffrey Scrope

On the first day of February 1328 King Charles IV of France, third son of King Philip the Handsome and last of the Capetian dynasty, lay dying. He had no children but his wife was pregnant. On his deathbed Charles said, If the Queen bears a son he will be King, but if she bears a daughter then the crown belongs to Philip of Valois.

Philip, Count of Valois, Anjou and Maine, was thirty-five, a tall, handsome nobleman who was famous for magnificence and for prowess in the tournament and on the battlefield. He was a great-grandson of St Louis and King Charless first cousin ; his father, Charles of Valois, had not only been a Prince of the Blood Royal but also, because of his second wife, titular Emperor of Constantinople; while Philips mother had been a daughter of the Capetian house which ruled Naples. He had inherited vast wealth and estates. Cold and calculating, he was very different from the flashy and incapable knight-errant of popular tradition.