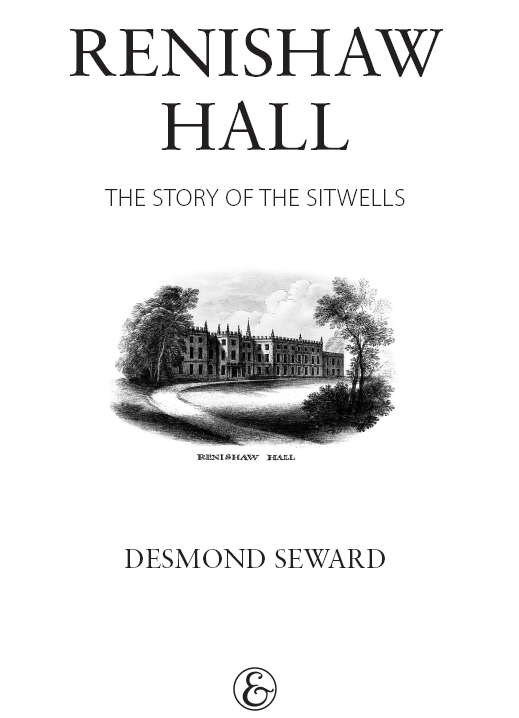

RENISHAW

HALL

In memory of Reresby Sitwell

CONTENTS

An ancient hall without its records is a body without a soul and can never be fully enjoyed until one has learnt something of the men and women whom it has sheltered in the past of their lives and manners, their love affairs, their wisdom and their follies; how the oak furniture gave way to walnut, and the walnut to mahogany; how they laid out the gardens, raised the terrace, clipped the hedges, and planted the avenue.

SIR GEORGE SITWELL, INTRODUCTION

TO LETTERS OF THE SITWELLS AND SACHEVERELLS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is a book about the Sitwell family and Renishaw Hall, where they have lived since 1625. I am most grateful to Alexandra Sitwell (Mrs Rick Hayward) for asking me to write it and to Penelope, Lady Sitwell for encouragement, as well as invaluable information.

I must also thank Christine Beevers, an archivist whose suggestions and encyclopedic knowledge of the source material at Renishaw have been of enormous help throughout as in finding unpublished letters from Evelyn Waugh and Dylan Thomas. Others who gave me information or advice were: Julian Allason; Gillian, Lady Howard de Walden; Stella Lesser (who read the proofs); Anna Somers-Cocks; and James Stourton.

I have been lucky to have such an unusually understanding and patient editor as Pippa Crane while, as so often before, I owe a special debt to my agent Andrew Lownie for his unfailing support.

Desmond Seward

Hungerford, 2015

FOREWORD

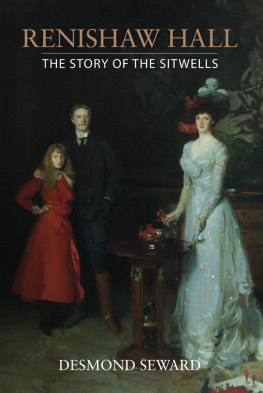

During the 1920s three writers, Osbert, Edith and Sacheverell Sitwell, became the generally acknowledged rivals of the Bloomsbury Group. According to their friend Evelyn Waugh, they radiated an aura of high spirits, elegance, impudence, unpredictability, above all of sheer enjoyment. They declared war on dullness.

Behind the Trio stood Renishaw Hall in Derbyshire, the familys home since 1625, which down the generations has affected everybody who lived there. In a beautiful setting, filled with treasures, it enchanted all three when they were young. The Sitwells might wander far from Renishaw, but they would always return in spirit, wrote Harold Acton. Rex Whistler, no stranger to great mansions, thought it the most exciting house in England, while it replaced Madresfield in Evelyn Waughs affections. Osberts lasting achievement was commissioning John Piper to paint it.

Unfairly, the Trio blamed their father Sir George for failing to save their beautiful, brainless mother from a prison sentence, while they resented being dependent on him for money. Osbert and Edith turned him into a figure of fun in their autobiographies, a caricature accepted unquestioningly by everyone who writes about the Sitwells. So far, nobody has acknowledged just how much he formed the minds of his children. For, while undeniably eccentric, he was also brilliantly gifted a pioneer in re-discovering Baroque art, and one of the finest landscape gardeners of his day. Above all, he was the creator of modern Renishaw.

His childrens impact on the arts and their role as arbiters of taste have been forgotten (even if Ediths verse still has admirers); so too has their feud with Bloomsbury, and all the malicious gossip that accompanied it. Yet their friends included Aldous Huxley, Siegfried Sassoon, Anthony Powell, L. P. Hartley, Dylan Thomas, Graham Greene and (up to a point) Virginia Woolf. Osberts closest literary friendship was with Evelyn Waugh.

However, the Trio are just a part of this modest chronicle of Renishaw Hall and its squires. Among the owners have been a Cavalier, a Jacobite, and a Regency Buck who added palatial new rooms. Not least was the maligned Sir George Sitwell, who, besides transforming the houses interior, created the gardens. The books climax is Renishaws triumphant restoration.

Chapter 1

THE CAVALIER

o portrait survives of the George Sitwell who built Renishaw Hall, but in 1900, after a close examination of the effigy on his monument in Eckington church and of his letter-book, another George Sitwell imagined how he must have looked towards the end of his life:

o portrait survives of the George Sitwell who built Renishaw Hall, but in 1900, after a close examination of the effigy on his monument in Eckington church and of his letter-book, another George Sitwell imagined how he must have looked towards the end of his life:

over the middle height, and, as became one obviously well advanced in middle age, rather neat and precise than fashionable in his dress. He wore a long periwig scented with orange water, a slight moustache and a tuft of hair upon his chin [...] His face, with its good forehead and eyes, strong and clear-cut nose and well developed chin, gave an impression of force of character, tenacity of purpose, and good reasoning powers, and this impression was strengthened by his conversation, for even the most casual acquaintance could not fail to observe that he was a manufacturer who had been accustomed to think and act for himself, a man who was not only well educated, but gifted with a sound judgement and a marked talent for business.

Born in 1601 at Eckington in Derbyshire, George was the son of a rich yeoman (also called George), who lived in a house on the village street and died six years later. In 1612, Mr Wigfall, who was then of smale estate, marryed my mother, by which meanes he raised his fortune and came to have the guidance of mine estate dureing mine minority (which was about ten yeares), wrote George in 1653. Despite promising to leave him his property as settlement of a debt for 1,400, Wigfall married again after the death of his wards mother and, dying intestate in 1641, ensured that it went to the children of his second marriage, much to Georges anger.

With funds provided by Mrs Sitwell, Mr Wigfall had built them a house on the summit of a long, rocky promontory above Renishaw, a small hamlet near Eckington in the area then known as Hallamshire on the northern border of Derbyshire and the southern of the West Riding of Yorkshire. Six miles from Chesterfield and six from Sheffield, Renishaw lies between the Peak District and what are now called the Dukeries. Wigfalls new home, where the Renishaw stables now stand, must have alerted his stepson to the beauty of the site.

In 16256 (the first year of King Charles Is reign), using money saved during his minority, George built Renishaw Hall within sight of Wigfalls dwelling. A Pennine Manor on an H plan, this would become the nucleus of todays Renishaw. In some ways George always remained a farmer here, eating with his servants in the hall. Even today, when you go through the north porch into the hall which is not much changed since his day the panelling, huge fireplace, stone floor and rough oak furniture have a distinctly rustic feel.

On three floors, the tall, gabled house nevertheless aspired to gentility. From the hall, a door at the right opened on to a Little Parlour, and another door at the right on to a buttery and kitchen. The Great Staircase and Great Parlour (now Library) were at the left. Thirty-four feet long, twenty wide, with a bay window on to the gardens, the Great Parlour was the best room. Panelled, this had a plasterwork ceiling and a frieze of mermaids and dolphins, squirrels, vine leaves and grapes, with a large oak carving over the fireplace of Abraham sacrificing Isaac. Above the hall was the principal bedroom, the Hall Chamber, with Mr Sitwells study next to it.

Around the house were gardens and orchards, some walled. A large south garden, wider than the house it surrounded on three sides, had green or gravel walks, box hedges, small knot gardens with aromatic herbs, yew pyramids and flowerbeds. On the left was a bowling green. The Great Orchard, south of the main garden, contained two archery butts and side alleys bordered by flowers. There was also a banqueting house of red brick that contained a tiny, oak-panelled room. A brew-house supplied the hall with beer until 1895.

Next page

o portrait survives of the George Sitwell who built Renishaw Hall, but in 1900, after a close examination of the effigy on his monument in Eckington church and of his letter-book, another George Sitwell imagined how he must have looked towards the end of his life:

o portrait survives of the George Sitwell who built Renishaw Hall, but in 1900, after a close examination of the effigy on his monument in Eckington church and of his letter-book, another George Sitwell imagined how he must have looked towards the end of his life: