I am afeard there are few die well that die in a

battle; for how can they charitably dispose of any

thing when blood is their argument:

William Shakespeare, Henry V, Act 4, Sc. 1

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright text David Baldwin 2006.

Unless otherwise stated, all photographs in the plate section are Geoffrey Wheeler. All text figures are Geoffrey Wheeler.

ISBN 1-84415-166-2

ISBN 978-1-84468-339-0(ebook)

The right of David Baldwin to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13 Ehrhardt by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire Printed and bound in England by CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

(between pages 78-9)

The battle of Stoke, the last and perhaps least known conflict of the Wars of the Roses, is undoubtedly one of historys might-have-beens. The engagement, fought on Saturday 16 June 1487 between the forces of King Henry VII and a rebel army commanded by John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, Richard Ills nephew, lasted for longer, and claimed many more victims, than the more famous battle of Bosworth two years earlier, but did not result in the death of a king or a change of dynasty. It has therefore been largely disregarded, although the situation in 1487 mirrored the unlikely circumstances in which Henry had destroyed Richard and the former might now have fallen victim to his own strategy. For the second time in under two years a rebel army, stiffened with a substantial number of foreign mercenaries, confronted a recently crowned king in the very heart of his kingdom, and the crisis of loyalty which paralysed the royal army at Bosworth was matched by an equally dangerous crisis of confidence among the Tudor forces before Stoke. There was one crucial difference: King Henry, rightly, gave priority to his own safety, while his rivals, more impetuous, lost both their lives and their cause. But it is likely that, had Lincoln won, Bosworth and the Tudor dynasty would have been relegated to a footnote of history, and the House of York would have governed for many more years.

Stoke Field has been considered by a number of battlefield historians, Richard Brooke and Colonel Alfred Burne and another is that the work of Peter Newman and others has created a new discipline for the investigation and reconstruction of ancient battles which has not previously been applied to Stoke. I also wanted to go beyond the previous studies and discover why men were prepared to risk everything to help an obvious impostor rather than accommodate themselves to the new government. The old arguments that they fought because they were partisans of York or Lancaster, or because of their traditional allegiance to the Neville family, seemed less than satisfactory; and it was evident that some who joined the rebels had local differences with Tudor supporters and they with them. Those who had finished on the losing side at Bosworth now faced a bleak future, and it seemed that only Henrys overthrow could produce a national government more to their liking and, more importantly, remove personal enemies who enjoyed his favour. Defeat meant disaster, but victory would restore them to positions of authority within their regions as the loyal and valued servants of a new Yorkist king.

This, then, will be a story of people as well as an account of a military conflict, and I looked for an individual whose life would act as a focus for the whole narrative. Like Barbara Tuchman, I wanted a male member of the second estate, i.e. a nobleman, and have chosen Francis, Baron, later Viscount, Lovel, who was probably Richard Ills closest friend and whose recorded career (1456-1487) spanned nearly the entire Wars of the Roses. No Lovel family archive has survived and a conventional biography is impossible. But there are documents which cast light on him in other collections, and many of these relate or can be related to the events of 1486-7. His devotion to the Yorkist kings and consistent opposition to Henry VII make him a better vehicle for our purposes than others who were prepared to temporise or whose support for the Simnel rebellion is at best conjectural, and it is likely that he was in no small measure responsible for what, for Henry, was an uncomfortably close call.

No account of a medieval battle can claim to be definitive or the last word on the subject, but I have tried to provide a better understanding of the events leading to the conflict (correcting some mistakes and misapprehensions in the process), and to offer what I hope will prove to be a more accurate assessment of what happened on Stoke Field. The gaps in our knowledge have often been filled by speculation leading to differing interpretations, and there are still occasions when a choice has to be made between alternatives for which we possess little or no firm evidence. There are several conflicting versions of the route to Stoke taken by the rebels and the positions which the rival armies subsequently adopted on the battlefield (to mention just two examples), and I judged that there was no merit in simply repeating them. What I have tried to do is to distil what, on the balance of probability, seems to me to be the most likely scenario, and to give my reasons for preferring it. Alternative versions are noticed principally in the Notes and References section, and readers can study these and compare them if they wish.

I would like to thank Rupert Harding for inviting me to undertake the book and for his continuing interest in it, Virginia Baddeley (Sites & Monuments Record Officer, Nottinghamshire County Council) and Mark Dorrington (Principal Archivist, Nottinghamshire Archives) for providing information and answering queries. I am particularly grateful to Glenn Foard (Project Officer of the Battlefields Trust) for allowing me to read and use the unpublished report of his preliminary survey of the battlefield of Bosworth, and to Geoffrey Wheeler for reading my manuscript, providing the maps and some of the illustrations and (with C.E.J. Smith) seeking out many obscure details. And lastly (as always) I would like to thank my wife, Joyce, for sharing her thoughts during several visits to the battlefield and for helping in many other ways.

David Baldwin

July 2005

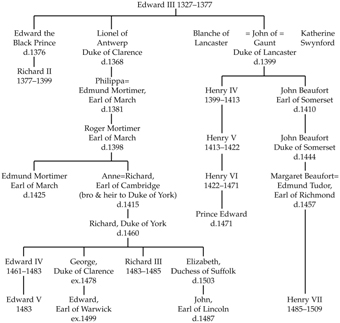

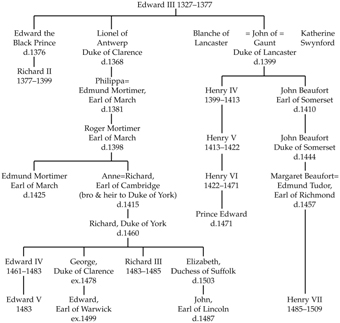

Prelude to Conflict:

The Wars of the Roses

The battle of Stoke was the culmination of a series of conflicts which convulsed England in the latter half of the fifteenth century and which Sir Walter Scott called the Wars of the Roses. and that most ordinary people were unaffected unless they happened to live near to a route taken by one of the armies. But four kings, Henry VI, Edward IV, Edward V and Richard III, were deposed (at least one, and possibly three, of them also died violently), and the leading noble families were decimated through two, or as many as three, generations. Overall, they claimed the lives of a larger proportion of the population of England than any conflict before the First World War.

Next page