Campaign 164

Otterburn 1388

Bloody border conflict

Peter Armstrong Illustrated by Stephen Walsh

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

ANGLO-SCOTTISH RELATIONS 132988

R obert Bruces great victory over the English at Bannockburn in 1314 loosened the grasp of Scotlands rapacious southern neighbour on the Northern Kingdom. Despite the magnitude of their defeat, the English refused to acknowledge Bruce as King of Scots or to recognize Scottish independence. In the years that followed Bannockburn, Scotlands hard-won military ascendancy allowed King Robert to unleash the destructive power of the Scots on the north of England in an attempt to force Edward II of England to conclude a peace that would not only recognize Robert as King of Scots but also acknowledge Scottish independence. The depredations of the Scots caused widespread devastation and ruined the economy of large areas of the northern counties, which were reduced to a pitiful condition. Despite the repeated harrying and spoliation of the north, Edward II remained indifferent to its plight. By 1327, Robert Bruce was worn out and ill, and though he was only 52 he was approaching the end of his life. His only legitimate son, David, who was to be his successor to the throne of Scotland, was still a three-year-old child. King Roberts aggressive policy towards England had not brought results and his aims seemed as far from being achieved as ever. Then, unexpectedly, events in England took a turn favourable to the Scots. In January 1327 the hapless and increasingly unpopular Edward II was deposed and his 14-year-old son was crowned in his place as Edward III on 1 February. A council of regency was established, dominated by Isabella the Queen Mother and her lover Mortimer, whose all-pervading influence corrupted the unpopular regime. The ailing King Robert responded to the situation in the south with a renewed onslaught on the northern counties of England. A disastrous and costly campaign in Weardale in July failed to dislodge the Scots, who not only continued to hold much of Northumberland, but began to take possession of their conquests by parcelling out land there on a permanent basis. Isabella and Mortimer realized they had to act but, knowing that the backlash of defeat would bring about their downfall, chose not to risk renewing the war against the Scots but to make peace. By the Treaty of Edinburgh that followed in 1328, England renounced her claim to sovereignty over Scotland, which settled the question of Scottish independence. The treaty marked the conclusion of the long, damaging war that had first flared up in 1296. Robert Bruces aggressive policy towards England had succeeded and set a precedent for generations of succeeding Scottish policymakers. Yet it was all for nothing; the peace that followed did not long outlive King Robert himself who died, in June 1329 at the age of 54, worn out and racked by illness. His legacy of achievement would not be matched by his successors to the throne of Scotland. He was succeeded by his seven-year-old son David, who was crowned at Scone in November 1331 as King David II. The ensuing festivities proved to be the high water mark of Scottish fortunes in the Wars of Independence, for a new and disastrous phase was about to begin.

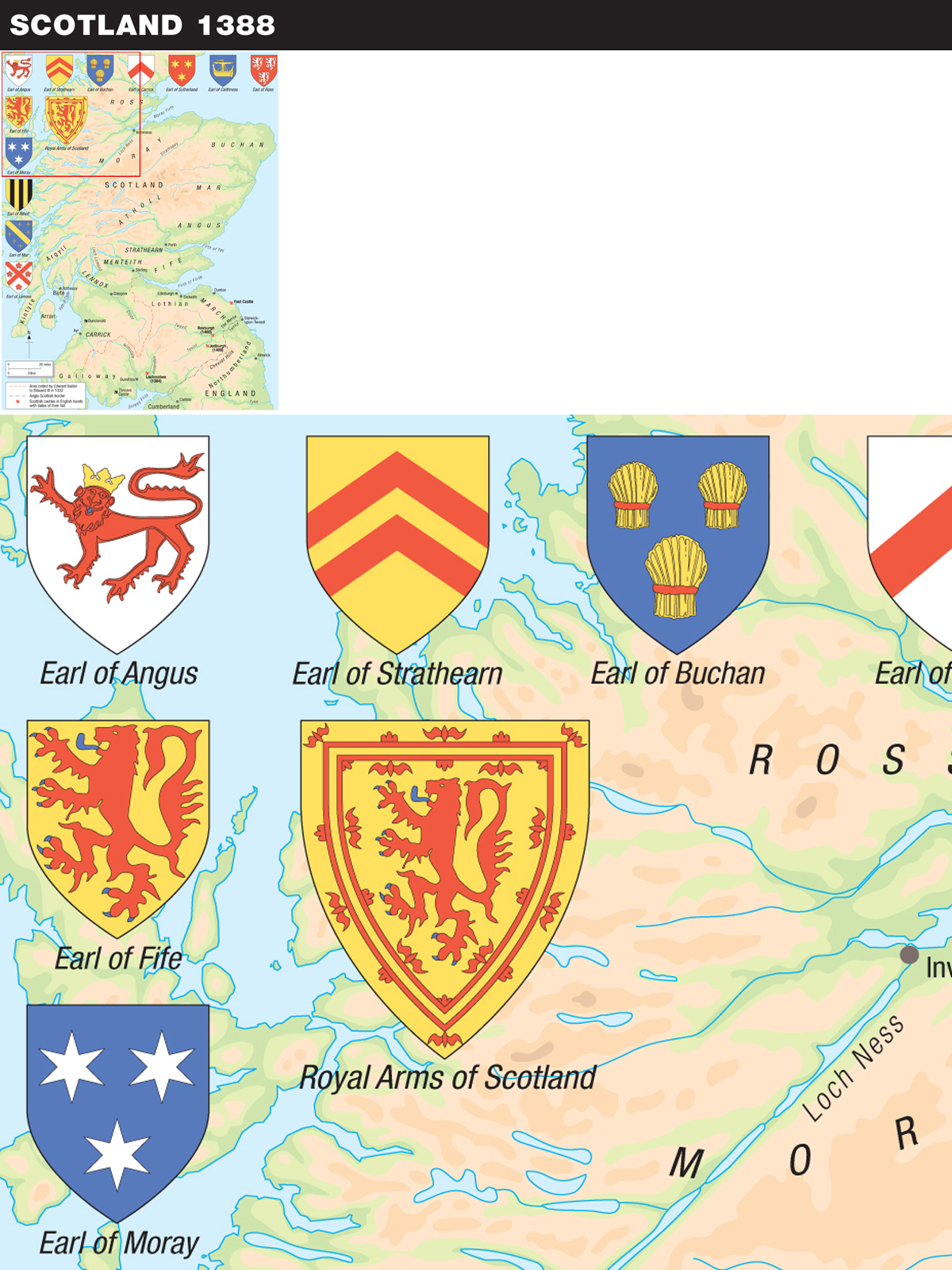

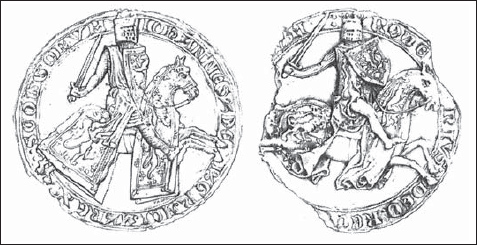

The early phase of the Scottish Wars of Independence took place during the reigns of John Balliol (129296) and Robert I (130629). Their equestrian seals display the Royal Arms of Scotland, which symbolize the nations strength and independence. The lion rampant of Scotland was first used by William the Lion (11431214). His son, Alexander II (121449), added a bordure of fleurs-de-lis. The double tressure flory-counter-flory was first used on the great seal of Alexander III in 1251. (Authors drawings)

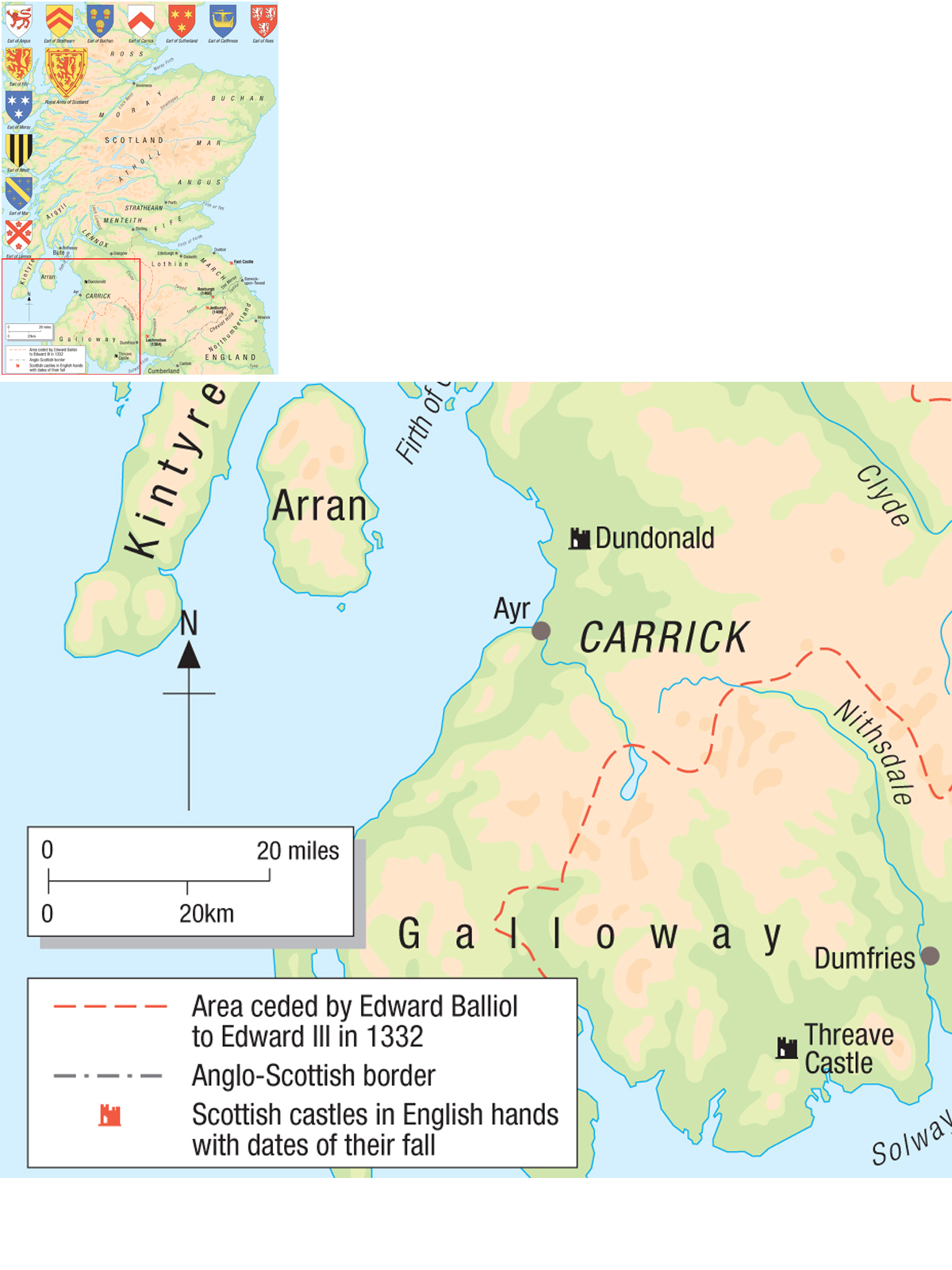

Edward Balliols return to power in 1333 was short lived, and his authority and the territory over which he held sway rapidly diminished. In 1356 he resigned his crown and retired to Yorkshire where he died in obscurity in 1364. For a time there were two kings of Scotland as Balliols reign overlapped that of David Bruce. (Authors illustration; McGarrigle Collection)

In 1330 Edward III overthrew Mortimer in a palace coup at Nottingham and took control of the government himself. Though he was not yet 18, he was cast in the mould of his grandfather Edward I, the hammer of the Scots. He was resentful of the Treaty of Edinburgh and burned for vengeance for the humiliation of his father at Bannockburn and for the recent fiasco in Weardale. In 1332 Edward covertly sponsored an audacious private invasion of Scotland by a group of self-seeking adventurers who had been disinherited by Robert Bruce and who sought to regain their inheritance by force of arms. They were led by Edward Balliol, son of John Balliol, King of Scots, whom Edward I had deposed in 1296. With scant regard for Scotlands independence he paid homage to Edward III for his kingdom before his expedition sailed. An extraordinary victory at Dupplin Muir, outside Perth, resulted in Balliol gaining the crown of Scotland, and, though he was ejected from the country by the end of the year, he was returned to power in 1333 after Edward IIIs victory over the Scots at Hallidon Hill beside Berwick. The tide had turned, the short-lived military supremacy of the Scots was gone; the day of the English long-bowman had dawned.

The price of Edwards support of Balliol was high; in addition to paying homage for his kingdom to Edward he was forced to cede permanently large areas of southern Scotland to England. David II took refuge in France where Philip VI, obliged by the auld alliance between France and Scotland, provided a safe haven for the young king. It was not until 1341 that the situation in Scotland allowed him to return home. The auld alliance with France, which was initiated in 1326 by the Treaty of Corbeil, was the cornerstone of Scottish foreign policy until the Reformation. It was a lopsided arrangement, which obliged the Scots to intervene in any Anglo-French conflict but was without a reciprocal agreement; French obligations were ambiguous, though they promised French support and an end to Scottish isolation in European affairs. It was an arrangement calculated to sour relations with England and left the two countries locked in a cycle of hostile truces and occasional outbreaks of open warfare.

Next page