Campaign 121

Quebec 1759

The battle that won Canada

Stuart Reid Illustrated by Gerry Embleton

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

James Wolfe; this portrait by Joseph Highmore, which was probably painted to celebrate either his appointment as major in the 20th Foot or his promotion to lieutenant-colonel a year later, brilliantly captures his youthful self-confidence and also a certain dry humour. (National Archives of Canada C-003916)

U ntil the middle of the 18th century, the increasingly prosperous British colonies in North America were effectively confined to the eastern seaboard of the continent by the long Appalachian mountain chain. However, in the early 1750s an attempt by land speculators to move across the mountains and into the Ohio Valley brought the Virginian colonists into direct and disastrous conflict with their French neighbours. The twin French colonies of Canada and Louisiana were connected by a tenuous overland route down the Ohio and Mississippi valleys and the prospect of American settlers establishing themselves across it provoked an immediate response. When the American provincial troops, ineptly led by a young Virginian militia officer named George Washington, proved themselves quite incapable of fighting the French on anything approaching equal terms, British regulars were sent out for the first time under the unfortunate Major-General Edward Braddock. The French promptly responded by doing the same and what had begun as a boundary dispute initiated by land speculators rapidly escalated into a war to the death, in which British strategy aimed to seize the whole of French Canada.

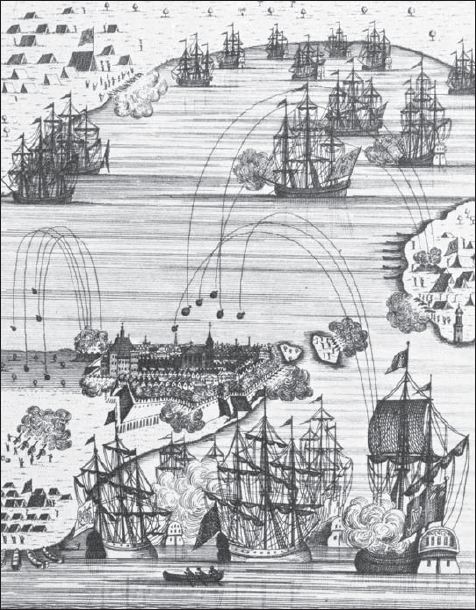

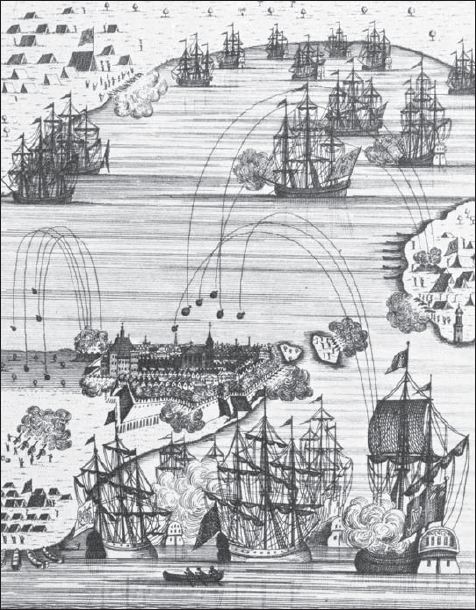

At first sight rather fanciful, this is in fact a fairly accurate depiction of the siege of Louisburg. It was Wolfe who seized Lighthouse Point on the right of the picture and established batteries that fired directly into the town a tactic he was to repeat at Quebec.

Edward Braddock, the ill-fated commander of the first British regulars to confront the French, is commonly dismissed as an ignorant martinet. In fact he took very considerable pains to prepare his army for service in the woods and, with a little more luck, might well have won the battle on the Monongahela, with incalculable consequences for the future course of the war.

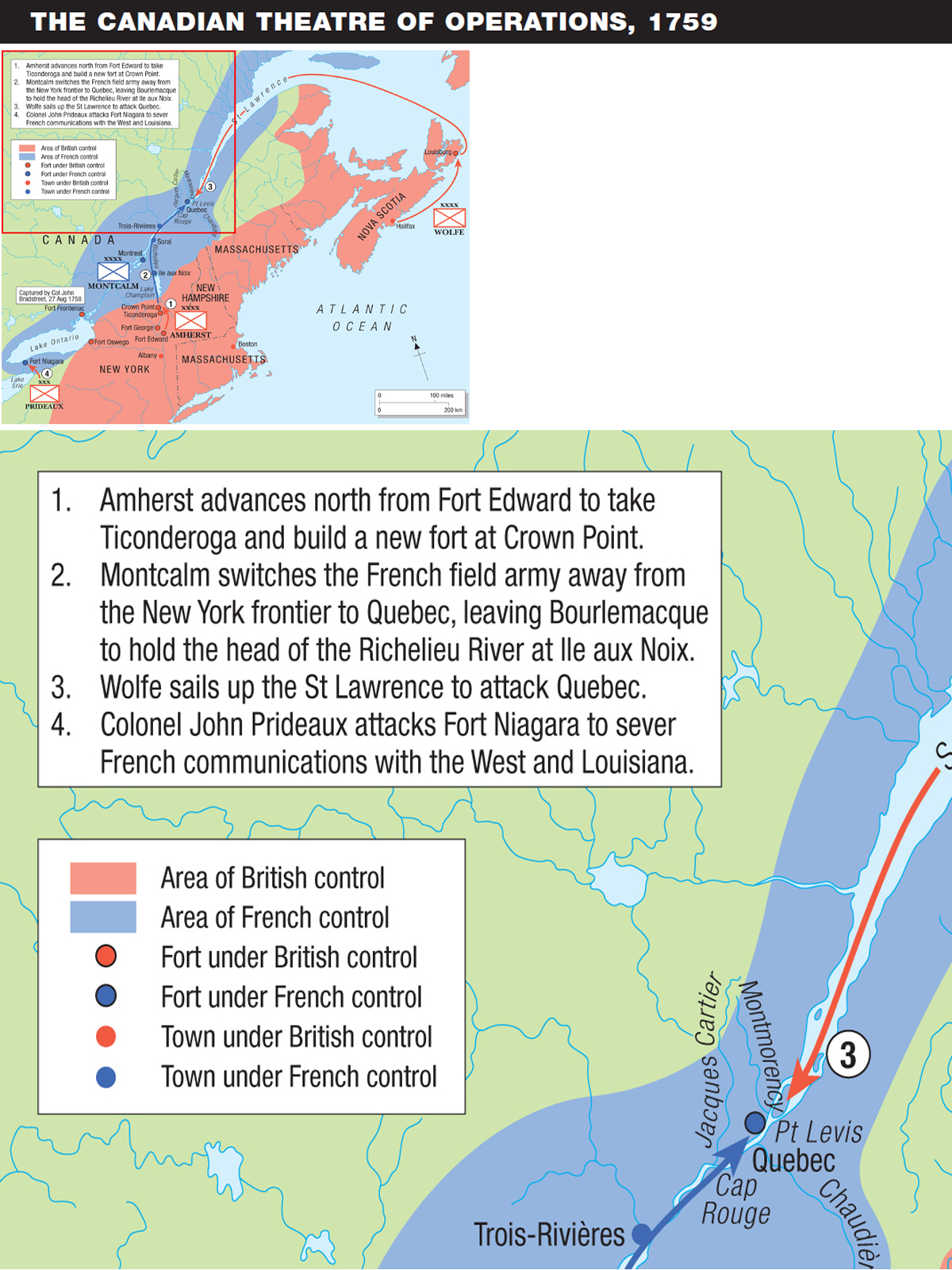

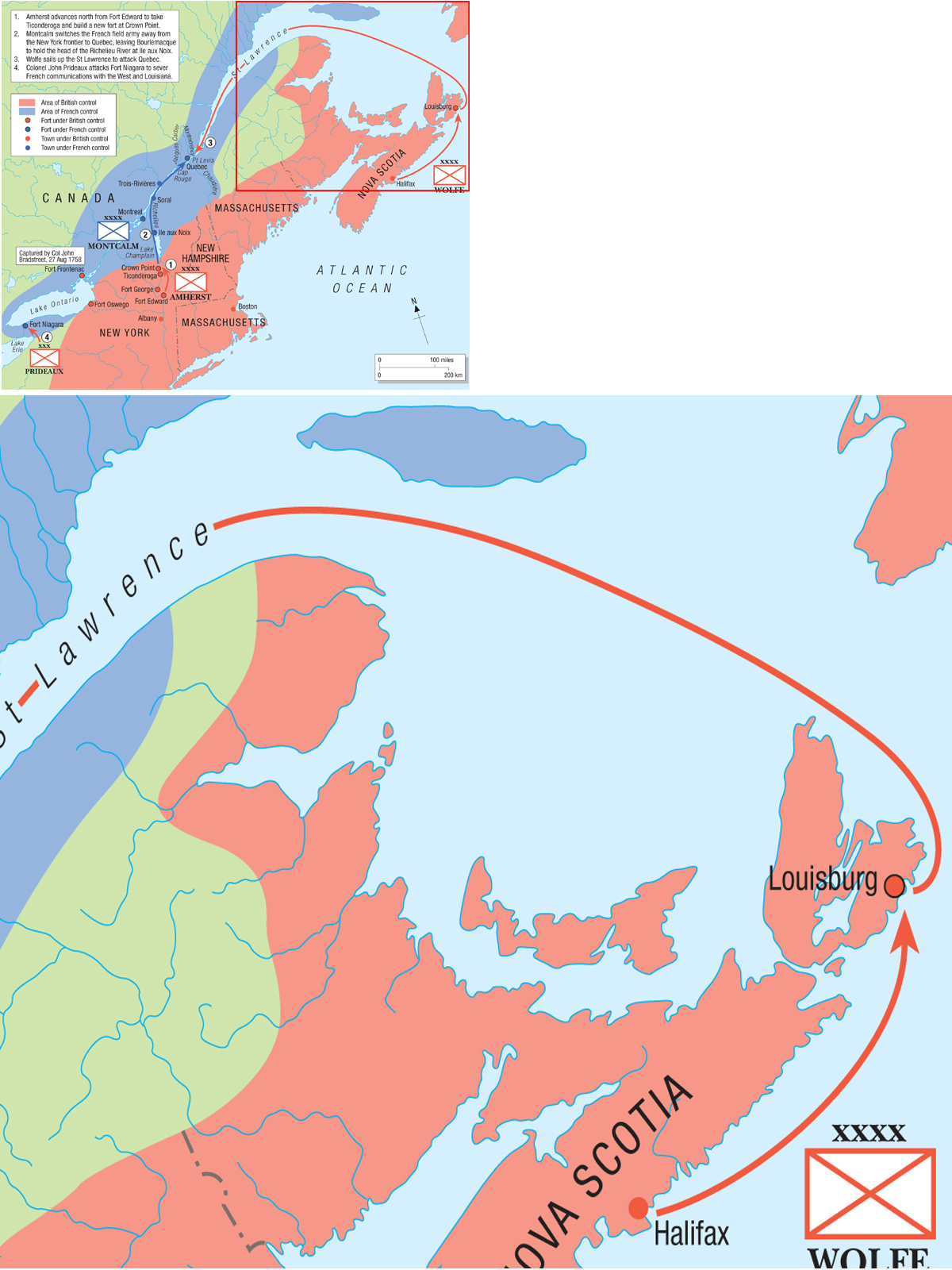

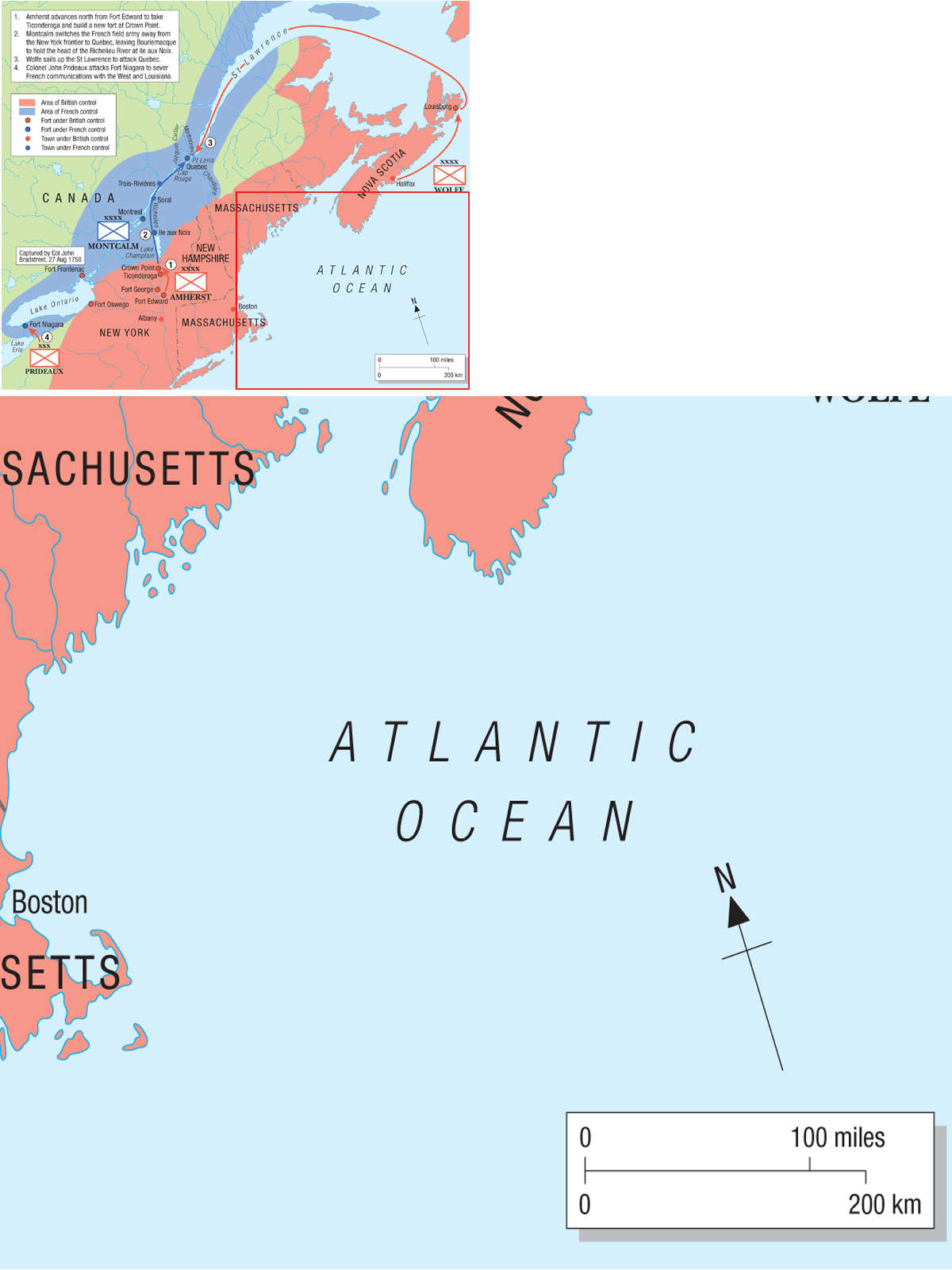

Notwithstanding some serious setbacks, by the end of 1758 the British Army was some considerable way to achieving this aim. Badly outnumbered, the French were forced to abandon the strategically important Forks of the Ohio virtually without a fight. Although the main British offensive up the Hudson Valley under Major-General Abercromby had been stopped in its tracks at Ticonderoga at the foot of Lake George, the massive fortress of Louisburg at the mouth of the St Lawrence River was captured by Sir Jeffrey Amherst after a conventional European-style siege.

That winter Amherst went to New York to assume command of Abercrombys defeated army and with it the post of Commander in Chief North America. His rather difficult subordinate James Wolfe sneaked off home with a view to obtaining a command in Europe. Instead, however, Wolfe found that plans were being laid in London for the final destruction of French Canada, and promptly put himself forward for the command of what promised to be the most important of three quite separate operations.

Back in the Americas, the bloodless capture of Fort Duquesne at the Forks of the Ohio and Colonel Bradstreets surprise seizure of Fort Frontenac during the previous summer was now to be followed up by an expedition against Fort Niagara under Colonel John Prideaux. Although the smallest of the three operations, it remained very important. Capture of the fort, lying at the mouth of the Niagara River, would not only completely seal off the overland route between Canada and Louisiana, preventing any retreat by the French Army in that direction, but it would also turn the flank of the defensive positions along the Upper New York frontier. It was here that Amherst, with a very substantial force of both regulars and provincials, aimed to succeed where Abercromby had failed, taking first Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga) and Fort St Frederic (Crown Point) and then pushing northwards to Montreal.

With the French Army occupied in dealing with these twin offensives, James Wolfe was to sail up the St Lawrence River and launch a direct assault on the capital of French Canada itself, the mighty fortress city of Quebec.

CHRONOLOGY

1748

Ohio Land Company formed to exploit trans-Allegheny country.

1754

July American expedition to Forks of the Ohio defeated by French at Great Meadows.

1755

April British regulars sent to North America.

June Unsuccessful attempt to intercept corresponding French reinforcements at sea off Grand Banks results in war.

9 July Major-General Braddock defeated and killed at Monongahela.

1756

11 May Marquis de Montcalm arrives in Canada with reinforcements.

1757

9 August Lieutenant-Colonel Monro surrenders Fort William Henry to Montcalm. As the garrison marches out, Indian allies of the French massacre between 80 and 200 before Montcalm restores order.

1758

27 July The British capture Louisburg.

8 July Abercrombies attempts to capture Fort Ticonderoga are repulsed.

27 August Colonel John Bradstreet captures Fort Frontenac at the entrance to the St Lawrence on Lake Ontario.

24 November Faced with the advance of Brigadier-General John Forbes expedition, the French blow up and abandon Fort Duquesne (present day Pittsburg).

1759

27 June Expedition arrives at Ile dOrlans, close to Quebec.

29 June Moncktons brigade landed at Beaumont.

9 July Grenadier companies and Townshends brigade landed at Montmorency.

18 July Royal Navy penetrates the upper river.

25 July Having reoccupied Fort Oswego, Brigadier-General John Prideauxs expedition captures Fort Niagara. Prideaux is killed during the siege.

26 July Amhersts expedition captures Fort Ticonderoga.

31 July