Campaign 123

Auldearn 1645

The Marquis of Montroses Scottish campaign

Stuart Reid Illustrated by Gerry Embleton

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

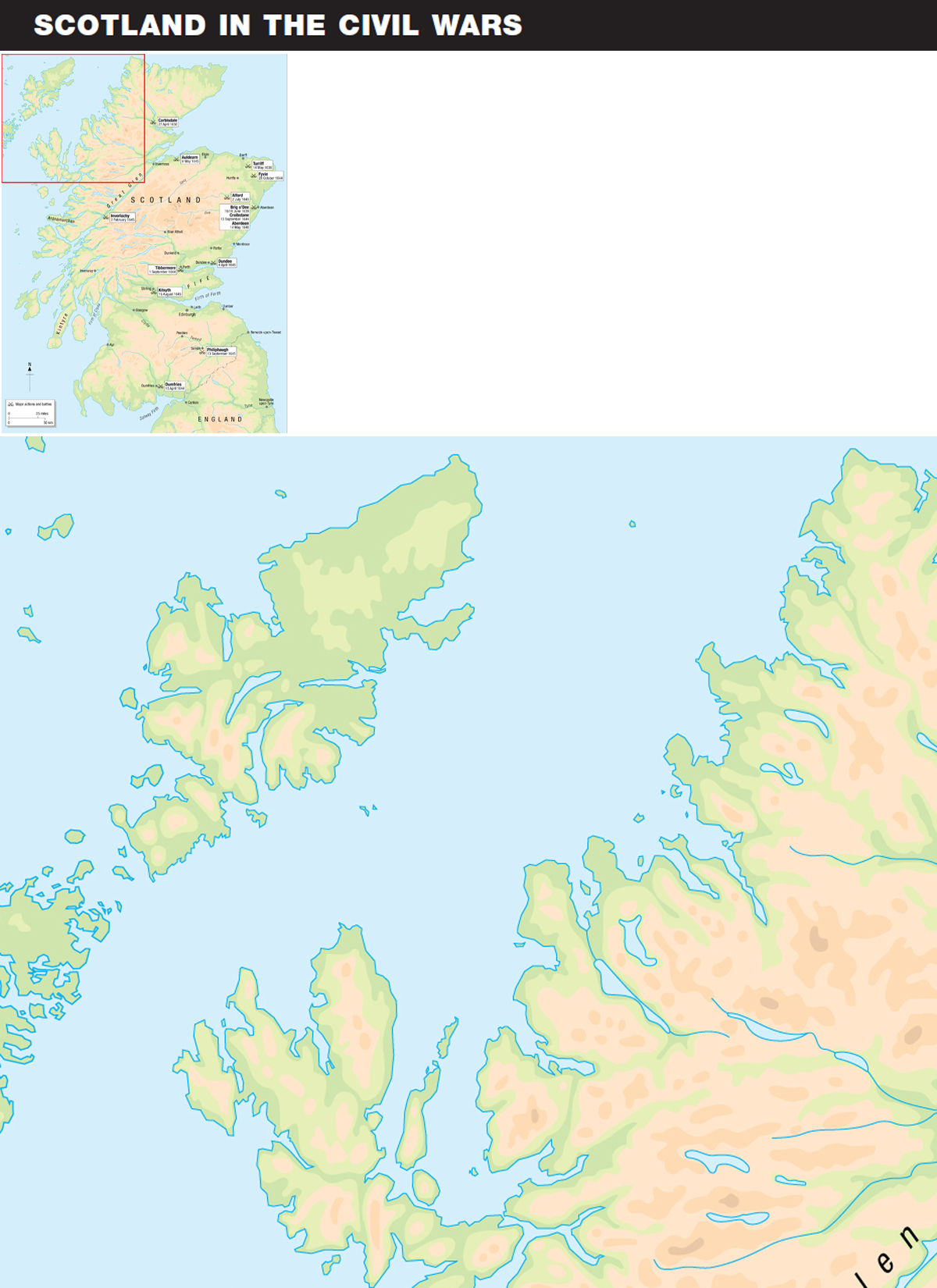

S cotland in the 17th century was an independent country whose king quite fortuitously happened to be King of England as well. From choice Charles I based himself in his richer southern kingdom and took little interest in Scots affairs until his belated coronation in 1633. A slow but steady slide into disaster followed. Two generations before, Scotland had firmly embraced the Protestant Reformation and in particular the teachings of John Calvin, but now the King, having remembered the existence of his northern kingdom, decided to remodel the Scots Kirk on Episcopalian or High Anglican lines. Quite literally smelling as it did of Popish incense this proposal was unpopular enough in itself, but worse was to come. In order to finance both the ecclesiastical reforms, and in particular the hierarchy of bishops that was to replace the democratic Presbyterian system, Charles also proposed to re-possess the former landholdings of the Catholic church. As in England, at the Reformation these vast lands had originally fallen to the Crown and then been sold on to the great benefit of the Exchequer. Now they were to revert to the Crown and although compensation was promised, the state was all but bankrupt and this was widely regarded as unlikely to materialise. Moreover in a culture where the number of a mans tenants was accounted of more worth than more material indicators of wealth, the potential loss of those tenants was a serious matter indeed. The result was that the proposed reforms not only alienated the Protestant population at large, but by directly threatening the wealth and above all the power of the nobility, they also provided the discontented with leaders.

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose. Initially an adherent of the Covenant he afterwards changed sides and, making common cause with the Catholic Earl of Antrim, he led a pro-Royalist uprising in a remarkable year-long campaign.

In 1638 a National Covenant was widely signed throughout the country, pledging a substantial part of the population, great and small, to oppose the Kings reforms. In 1639 and 1640 two brief and inglorious wars saw King Charles defeated and Scotlands independence very firmly re-asserted. From then onwards although lip-service was still paid to the King as the titular head of state, Scotland was a republic in all but name, and it was as a sovereign power that her government agreed to support the Westminster Parliament in the English Civil War that followed soon afterwards. Under the terms of the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643 Scotland was committed to enter that war with an army of over 20,000 men. Intervention on such a scale would be fatal to the English Royalist cause and so at Oxford an ambitious plan was set in train to knock Scotland back out of the war before it was too late.

There were three main elements to this plan. James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, himself a former Covenanter, was to lead a motley collection of Scots mercenaries and English levies northwards across the border from Carlisle to raise a rebellion in the old Catholic south-west. In the north-east of Scotland the long time Royalist George Gordon, Marquis of Huntly, was to lead a similar rebellion, while in the west Randal McDonnell, Earl of Antrim, was pledged to bring an army across from Ireland. What was more, and quite unbeknown to most of those involved, the garrison of Stirling Castle, traditionally the key to Scotland, was also disaffected and ready to go over to the rebels as soon as they appeared.

None of the rebels did appear, however. Huntly duly raised his followers as promised and took over Aberdeen, but the Irish never came and Montrose, having arrived rather too late on the scene, briefly occupied Dumfries before being ignominiously chased back across the border considerably quicker than he had come. The garrison of Stirling prudently sat tight, their putative treachery undiscovered, but Huntly, left isolated and alone, was forced to flee for his life and ever afterwards considered himself betrayed by Montrose. In any event it was all in vain. Montrose rode south to beg more men from the Kings nephew, Prince Rupert, but on 2 July 1644 the English Royalists northern army was smashed by an Anglo-Scots army on Marston Moor outside York and Montrose slipped home to Scotland without a single man at his back.

CHRONOLOGY

1644

19 January Scots Army led by Earl of Leven invades England

19 March Royalist uprising in Scotland begins, led by Marquis of Huntly

13 April Marquis of Montrose leads English Royalist army north to Dumfries

20 April Montrose flees back to England pursued by Earl of Callendar

29 April Huntlys Royalists evacuate Aberdeen and disperse

27 June Alasdair MacCollas Irish mercenaries sail from Passage near Waterford

8 July Irish land at Ardnamurchan

29 August Montrose is joined by MacColla and again raises the Royal Standard, this time at Blair Castle

1 September Montrose defeats Lord Elcho at Tibbermore, outside Perth

13 September Montrose defeats Lord Balfour of Burleigh at Aberdeen

28 October Indecisive engagement between Montrose and Marquis of Argyle at Fyvie Castle

13 December Royalists seize Inverary

1645

2 February Montrose defeats Argyle at Inverlochy

9 February Lord Gordon defects to the Royalists with a regular cavalry regiment

15 March Sir John Hurry successfully raids Royalist-held Aberdeen

4 April Montrose successfully storms Dundee but is summarily chased out again by Baillie and Hurry

9 May Battle of Auldearn. Montrose defeats Hurry

2 July Montrose defeats Lieutenant-General William Baillie at Alford

15 August Montrose again defeats Baillie at Kilsyth

13 September Major-General David Leslie defeats Montrose at Philiphaugh, near Selkirk.

1646

5 May King Charles I surrenders to the Scots army outside Newark, England