CAMPAIGN 192

NEW YORK 1776

The Continentals first battle

| DAVID SMITH | ILLUSTRATED BY GRAHAM TURNER |

| Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic |

CONTENTS

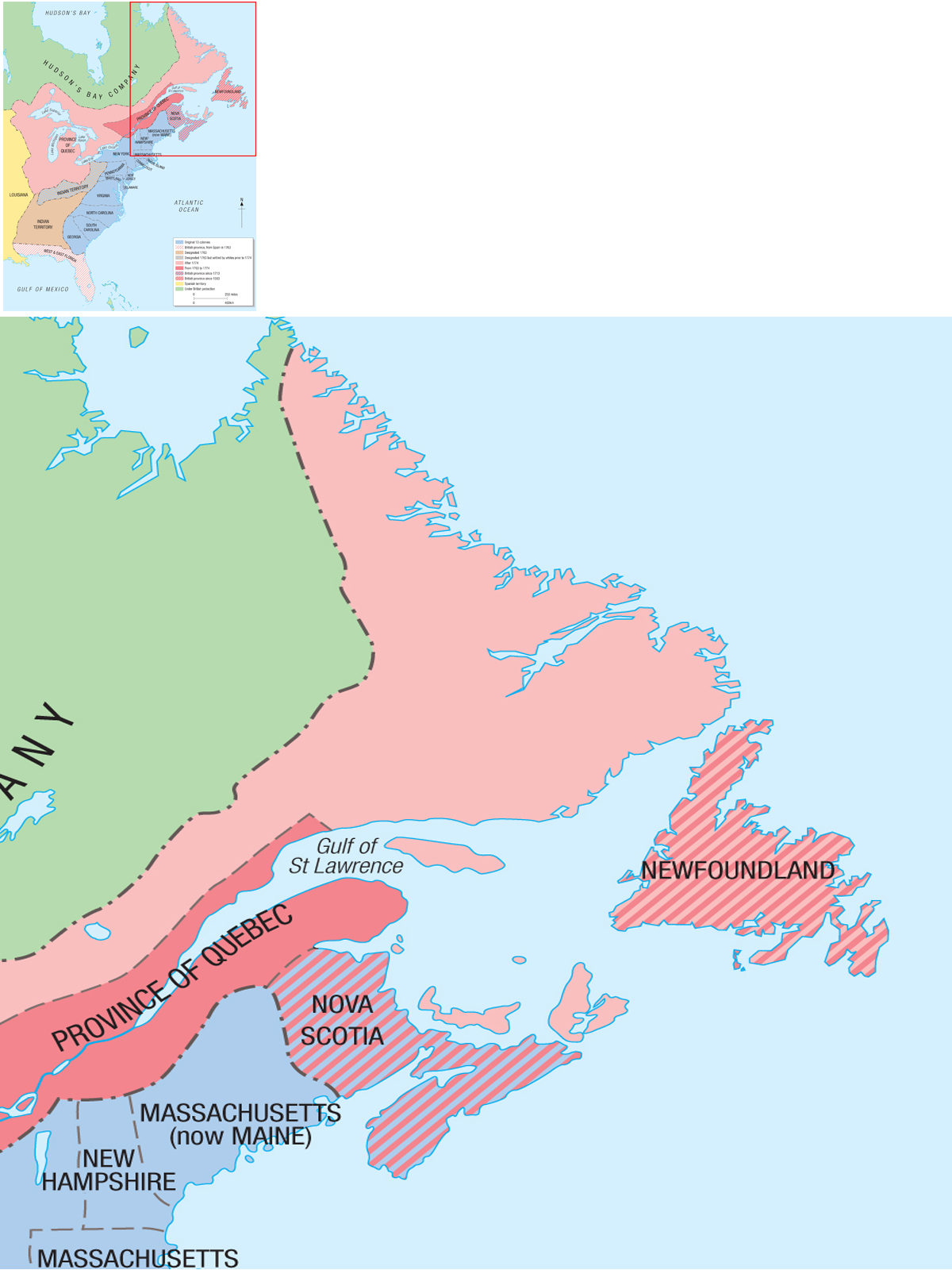

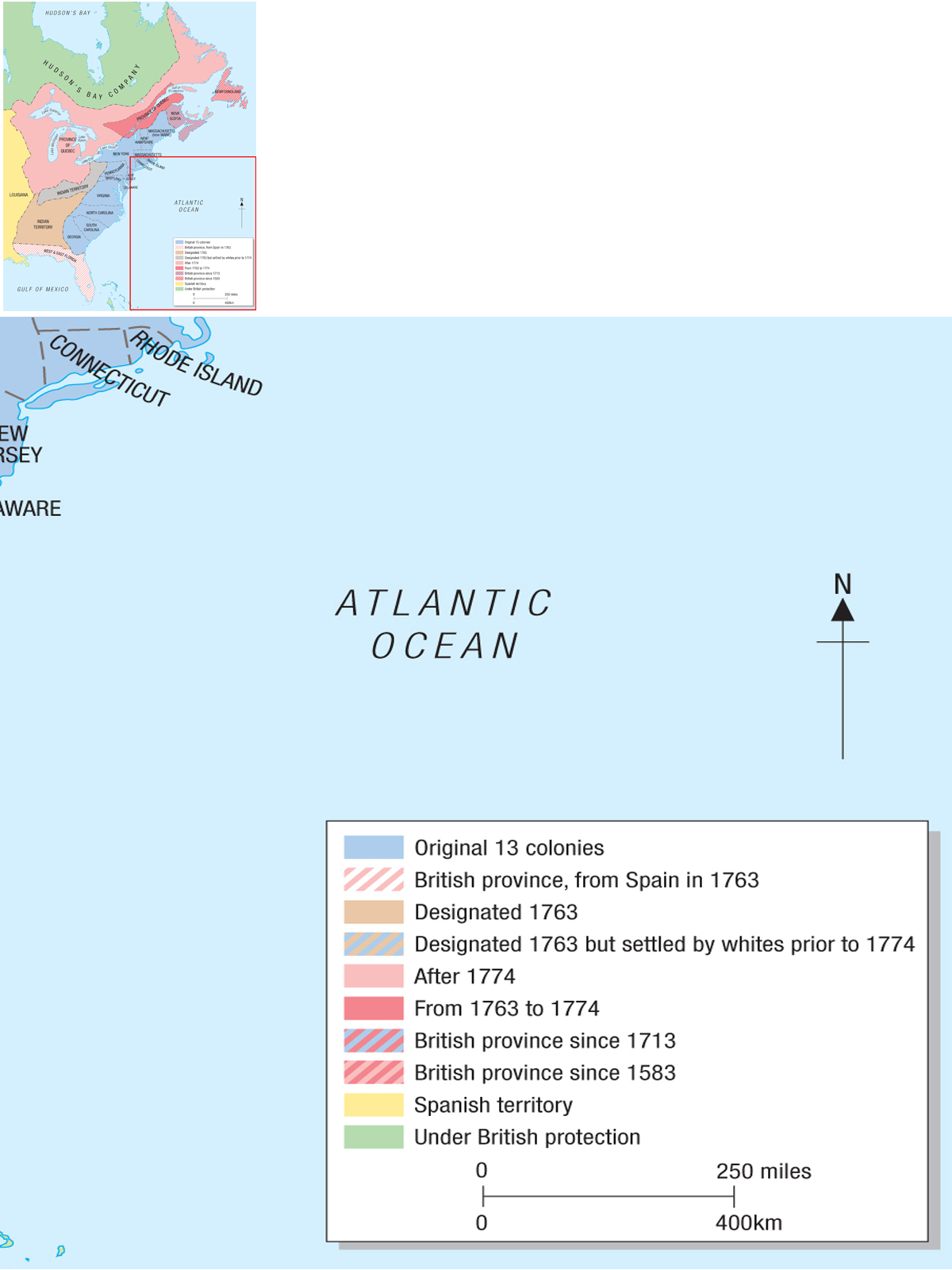

North America, 1776

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

As British regulars were sent reeling down Breeds Hill for the second time on June 17, 1775, it was no longer possible to pretend that a state of war did not exist between the mother country and her colonies. A scraped-together rebel army, ensconced behind strong fortifications, was inflicting over 1,000 casualties on the redcoats under Major-General William Howe, an appalling casualty rate. Ominously for the British, the Americans were standing firm in the face of massed ranks of professional troops, troops that may have expected to overawe their amateur opponents easily. Ominous for the Americans, of course, was the fact that the British returned for a third advance up the sides of Breeds Hill and, with the Americans running out of ammunition, finally broke through to take the position.

As Howe reflected on his victory (his report showed clearly what he thought: when I look to the consequences of it, in the loss of so many brave officers, I do it with horrorthe success is too dearly bought), the Americans must also have had mixed emotions. They had performed admirably in their first major engagement with regulars, but the determination of the British was frighteningly clear.

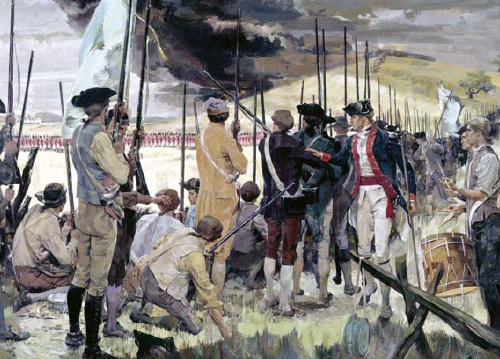

Bunker Hill had shown what the Americans could do if given the benefit of a strong defensive position, but early in the war Washington had no confidence in their abilities in the open field. (Domenick DAndrea)

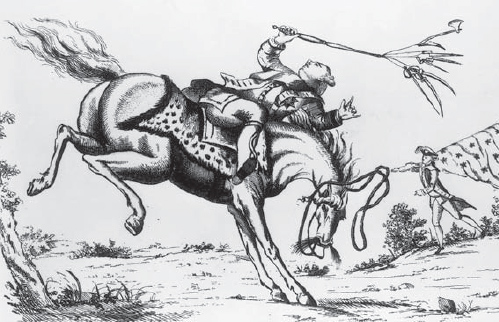

The Horse America throwing his Master. King George III is depicted as a hapless rider losing control of his mount. The Horse America looks full of fight and is not taking kindly to the bayonets, swords and hatchets with which the king is trying to subdue it. (LOC, LC-USZ62-1521)

It had been a bad year for the kings troops in the 13 colonies. The shot heard round the world had been fired just two months previously. A minor skirmish and harassed withdrawal at Lexington and Concord had now evolved into a siege at Boston, with the impertinent rebels closing in and British commanders and politicians finally realizing that this was no brief uprising to be quelled at the first appearance of substantial numbers of soldiers. In July Lord North wrote to the King, admitting that: the war is now grown to such a height, that it must be treated as a foreign war.

This raised the question of how the colonists could be brought back into the fold. This was not yet a war for independence. Rebel leaders merely wanted their rights as British subjects, as they saw themselves, to be respected. Whether a reconciliation could have been effected by a few simple concessions is an interesting point to debate, but the fact is that Britain chose to exert military force to bring the colonists back to their senses. Contrary to popular myth, the British did not believe they would simply roll over any resistance the colonists could offer. Experienced commanders knew that the vastness of the continent would work against them, as would the huge distances involved in providing and supplying a sizable armed force to operate in North America. Many officers and men had experience of fighting in the French and Indian War and were aware that warfare here was often very different from the large-scale affairs of European conflicts. Adjutant General Harvey commented that Taking America as it at present stands, it is impossible to conquer it with our British Army. To attempt to conquer it internally by our land force is as wild an idea as ever controverted common sense.

Howe himself saw Bunker Hill (as the engagement at Breeds Hill was to be remembered) as a blueprint for the failure of the British. From fortified positions the Americans could fight a defensive war to sap the strength of their opponents gradually. Refusing to be drawn into open engagements, they could force the British to attack prepared works and in this defensive mode, (the whole country coming into them upon every action) they must in the end get the better of our small numbers.

The latter part of Howes assessment may surprise some, but it demonstrates his awareness not only of the size of the British Army at the time (small by the standards of the day) but also of the difficulty involved in getting men to the colonies. In the war that was about to be waged, the burden of attaining victory was to lie squarely on Britain. The colonies merely had to avoid defeat.

The battle of Lexington. As George F. Scheer and Hugh F. Rankin state, The day of Lexington and Concord marked the transition from intellectual to armed rebellion. (LOC, LC-DIG-ppmsca-05478)

This political cartoon from 1775 shows the twin horses of Pride and Obstinacy carrying George III over a precipice, trampling the Constitution and Magna Carta at the same time. (LOC, LC-USZ62-12302)

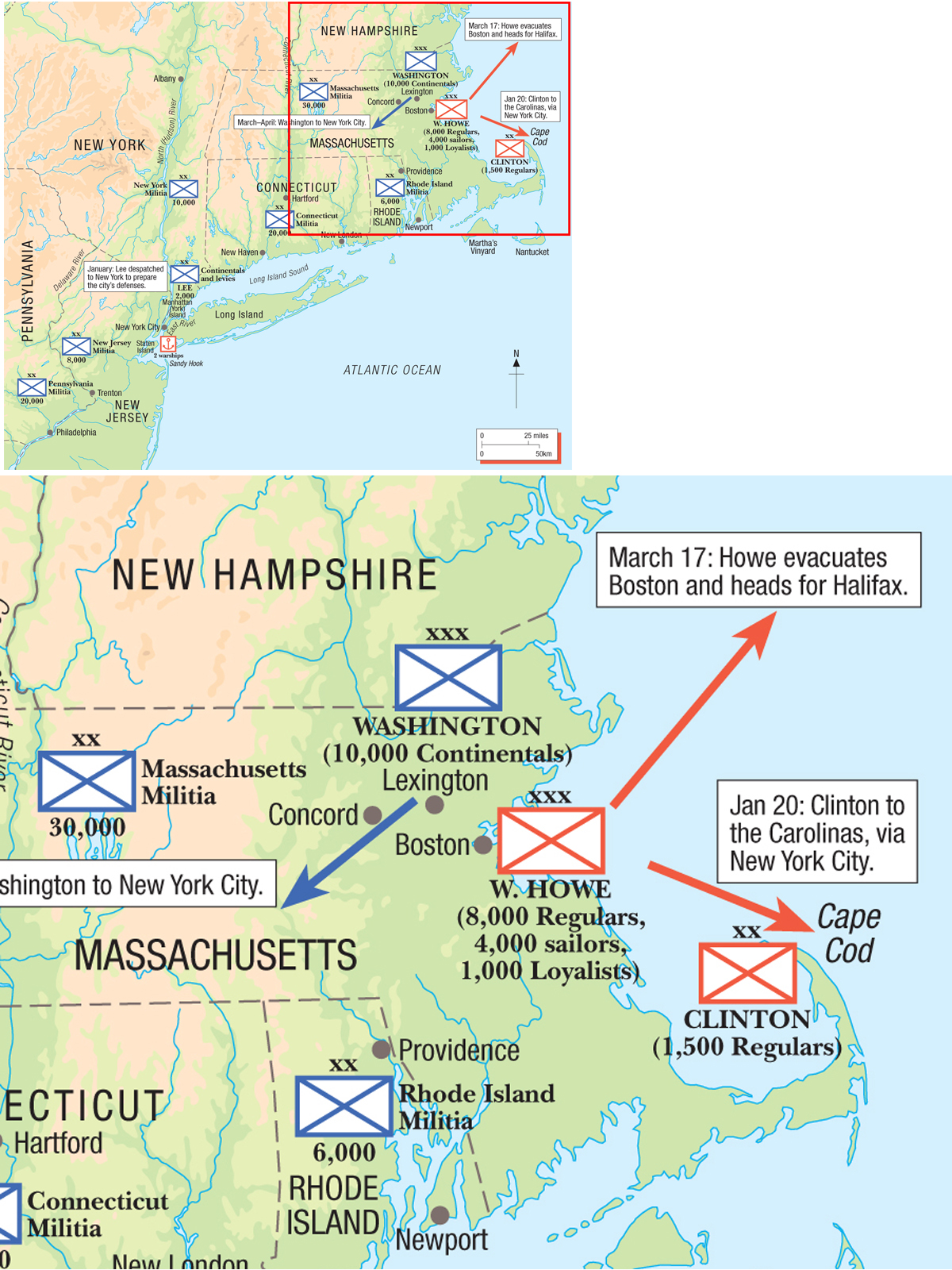

The first step in defeating the rebels would involve a shift of base. Besieged in Boston, Howe (who was appointed commander-in-chief of British forces in October 1775) could do nothing and was simply awaiting enough transports to move his army to the starting point for the 1776 campaign: New York. The move south would bring the British into an area of strong Loyalist support and enable the initiation of a new strategy, which involved the deceptively simple process of cutting the colonies in two along the Hudson River, thus dividing militant New England from the source of its supplies, the middle and southern colonies. Two British armies would undertake the workone, led by Howe, pushing up the Hudson from New York, the second, under Major-General Sir Guy Carleton, moving down the Hudson from Canada.

Howes retreat, spring 1776