Campaign 117

Stirling Bridge & Falkirk 129798

William Wallaces rebellion

Pete Armstrong Illustrated by Angus McBride

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGNS

SCOTLAND WITHOUT A KING

T he night of 18 March 1286 was to prove a fateful one for Scotland. In Edinburgh, after a day spent attending to affairs of state, King Alexander III of Scotland dined and drank with his counsellors. At length his thoughts turned to the attractions of his French wife the beautiful Yolande de Dreux whom he had married the previous October. She was at Kinghorn in Fife and Alexander resolved that he would ride the 22 miles to be with her despite the blackness of the night and the atrocious weather. As he and his companions made their way along a winding cliff-top path above the Firth of Forth the king became separated from his attendants. His horse stumbled and threw him and in the morning he was found on the shore, below the cliffs, with a broken neck Scotland was without a king.

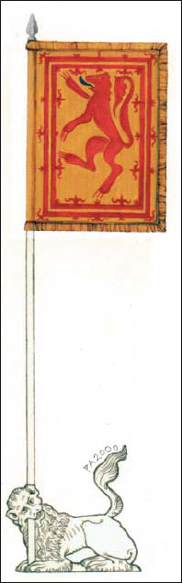

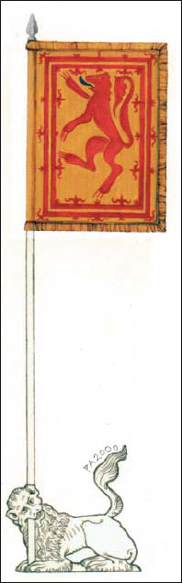

The lion rampant of Scotland was first used in the time of William the Lion (11431214), the bordure of fleurs de lys appeared during the reign of his son, Alexander II (12141249). The double tressure flory-counter-flory was first used on the great seal of Alexander III in 1251. (drawing by Pete Armstrong)

In retrospect Alexanders long reign was seen as a golden age of peace and prosperity but his achievements were undermined by his failure to provide Scotland with a legitimate male heir. His first wife Margaret, daughter of Henry III of England, died in 1275 and their children, two sons and a daughter, did not long outlive her. It had been hoped that Alexanders marriage to the young Frenchwoman might produce a male heir to rectify the situation but his untimely death left instead a sickly three-year-old as heir to his throne. She was Alexanders granddaughter whose mother, the queen of Eric II of Norway, died in 1283 giving birth to Margaret, the Maid of Norway, last of the royal house of Canmore. A council of regency was appointed to administer the kingdom in the name of Queen Margaret in distant Norway and a deputation was sent to Edward I, who at this time was embroiled in affairs in Gascony, to inform him of the situation in Scotland. No doubt the king considered the implications of events but at the time he took no action. When he returned to England, in the late summer of 1289, Edward proposed a marriage between his infant son, Edward of Caernarvon and the Maid of Norway. The Scots assented to this in the Treaty of Birgham in 1290 though the terms of the agreement warily insisted that the realm of Scotland was to continue as an entirely separate and independent kingdom.

But it was all for nothing as Margaret died shortly after landing in Orkney leaving the succession open again and bringing forth a rash of Competitors eager to stake their claim to the vacant throne. Realising the danger of this situation and the possibility of civil war, the Scots nobles invited the intervention of Edward I. In May 1291 Edward met the Scots on the Border at Norham on Tweed and informed them that he would judge the various claims to the throne though they must acknowledge him as overlord of Scotland and, to ensure peace, surrender the Royal Castles of the kingdom into his keeping. In the face of Edwards army gathering ominously nearby the Scots caved in and effectively put the country under his control. It is not clear at what stage in these events he decided on the subjugation of Scotland though it is possible that unfolding circumstances simply played into his hands. Edwards beloved wife Eleanor died in 1290 and the cast of the ageing kings mind darkened. The fall of Acre in 1291 ended Edwards dream of a new crusade in the Holy Land and without this distraction his thoughts returned increasingly to Scottish affairs.

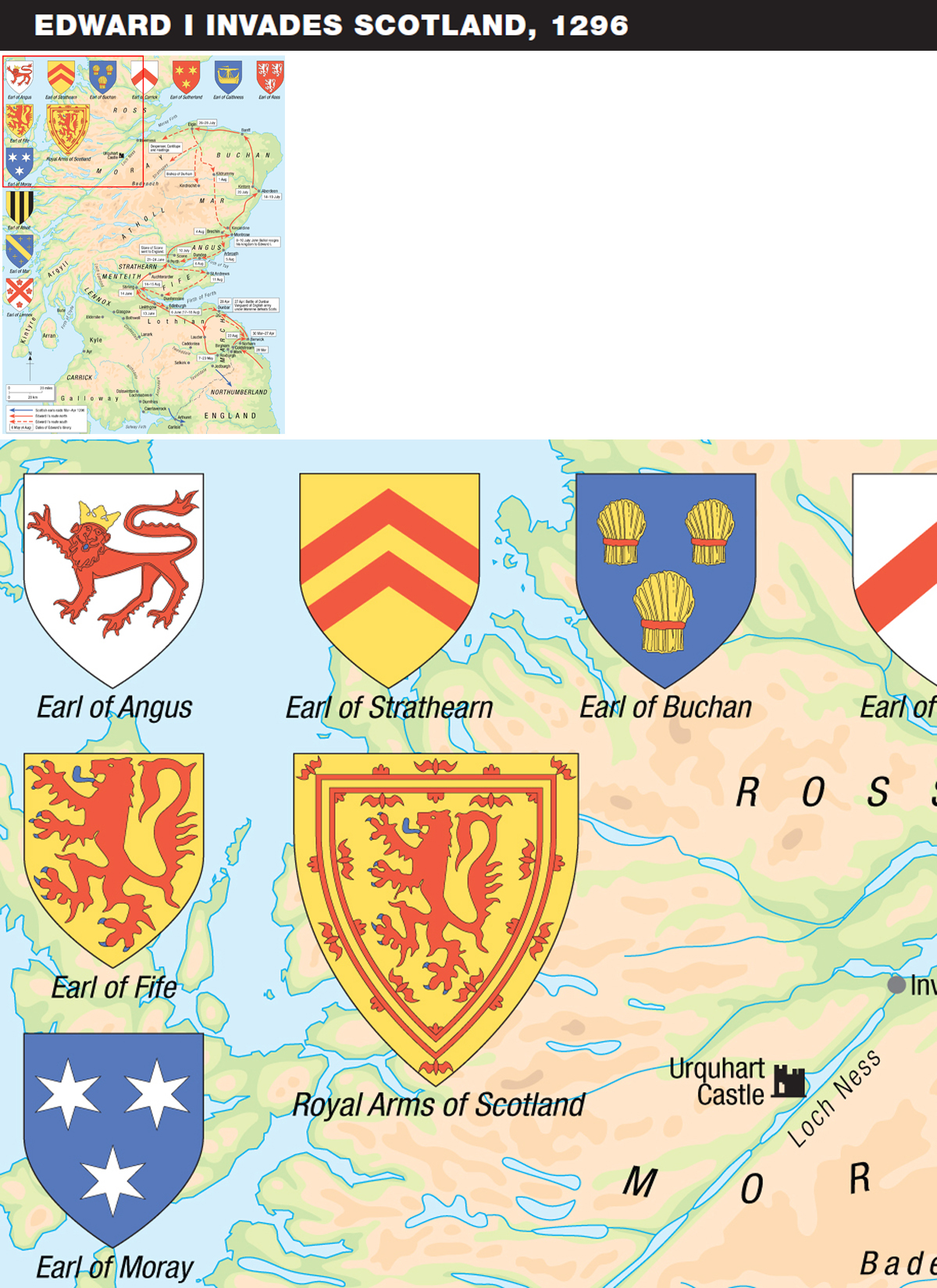

The Great Seal of John, King of Scots (12921306) bearing the inscription IOHANNES DEI GRACI REX SCOTTORUM John, by the grace of God, King of Scots. The Royal arms of Scotland are displayed on the shield and horse trapper, details are conventional other than the noteworthy Scottish form of the sword. (drawn by Pete Armstrong)

Norhamshire formed part of the County Palatine of Durham in the middle ages. The imposing ruins of Norham Castle, the 12th century stronghold of the bishops of Durham stand guard above a crossing of the River Tweed on the Anglo-Scottish border. (Keith Durham)

King John Balliol

The foremost of the 14 claimants to the throne were both descendants of the daughters of William the Lions brother, David, Earl of Huntingdon. They were the octogenarian Robert Bruce known as the Competitor (grandfather of King Robert I) and John Balliol. Balliol was a cultured, middle-aged Anglo-Norman nobleman with extensive estates in England, northern France and Galloway and though he had some support among the nobility of Scotland he was not generally well-known there. On 17 November 1292, at Berwick, Edward decided in favour of the claims of Balliol who rendered homage to him for his kingdom and was crowned at Scone later that month. Though Scotlands castles were nominally returned to King John the country still remained effectively under English occupation. Edward was determined to further demonstrate his dominance of Scotland by undermining the judicial independence of the kingdom. He demanded that Balliol appear in person in England to answer appeals against the judgements of the Scottish courts. In medieval law this prerogative of the overlord was held to be the very test of sovereignty. In this manner he sought to emphasise that Balliol, as his feudal vassal held his kingdom from the King of England, his overlord. Balliol was summoned to Westminster to answer an appeal by Macduff of Fife against a judgement imposed on him by the Scottish Parliament and though he refused to answer MacDuffs appeal, without consulting the people of his realm, the affair was a humiliation and diminished his authority with the Scottish magnates. In 1293 war flared up between Edward I and Philip IV of France over the sovereignty of Gascony. Edward sent a high-handed summons to his Scottish vassals, including King John and 18 Scottish lords, demanding feudal service abroad for their Scottish lands. With a newly constituted council of magnates at his back to stiffen his resolve, Balliol refused to comply. Instead he sent a deputation to Philip of France to seek his assistance. This resulted in the treaty that became known as The Auld Alliance and provided for a Scottish invasion of England if the English invaded France. Early in 1296 Balliol formally renounced his allegiance to the English king and war between England and Scotland became inevitable. John Balliol, who a contemporary chronicler described as a lamb amongst wolves, who dared not open his mouth, found himself at the head of a Scotland for once united in its determination to oppose the will of Edward Plantagenet.

Next page