Campaign 175

Remagen 1945

Endgame against the Third Reich

Steven J Zaloga Illustrated by Peter Dennis

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

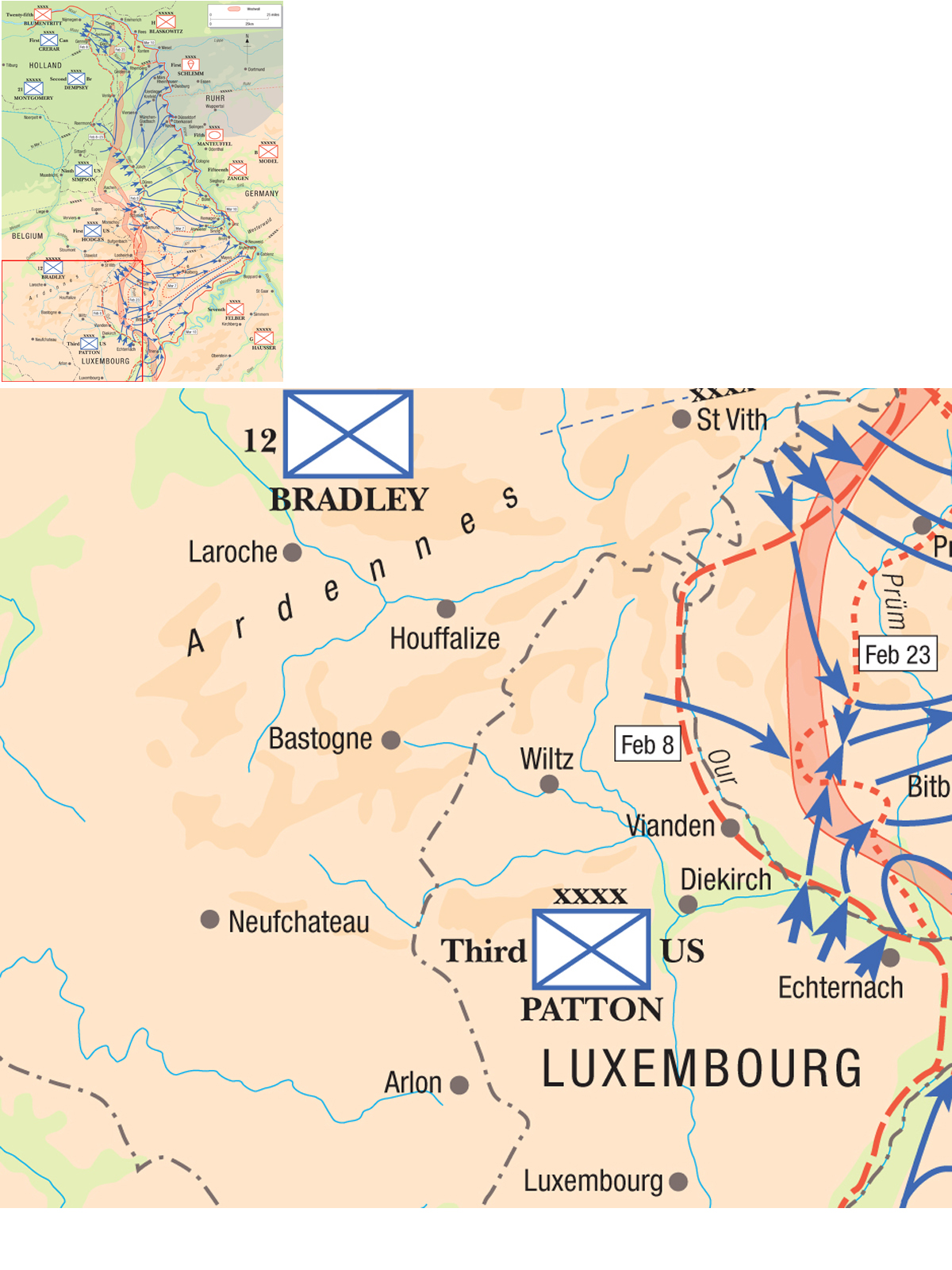

I n March 1945, the Rhine River was the last major geographic barrier to the Allied assault into western Germany. The Wehrmacht, bled white by horrific losses in personnel in the winter of 194445, pinned its hopes on the Rhine as the final defense line of the Third Reich. The capture of the Ludendorff railroad bridge at Remagen on March 7, 1945, provided the Allies with their first bridgehead over the Rhine. The capture was a surprise for both sides. The Wehrmacht had been demolishing all the Rhine bridges to prevent their capture and expected that the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen would be destroyed as had the others in the area. The Allies were already planning major operations to seize a Rhine bridgehead by amphibious assault, but in more favorable terrain north and south of Remagen. The unanticipated windfall at Remagen provided welcome opportunities for the US Army and significantly changed Allied planning for the endgame against the Third Reich. Instead of the deep envelopment of the vital Ruhr industrial region planned since the autumn of 1944, Bradleys 12th Army Group was able to conduct a much more rapid shallow envelopment, trapping Army Group B in the process. Hitler ordered Army Group B to defend the Ruhr instead of retreating to more defensible positions in central Germany, speeding their defeat. The destruction of Army Group B removed the most significant German formation in the west and hastened the end of the war. By early April, Eisenhower shifted the focus of the Allied offensive into Germany with Bradleys 12th Army Group as the vanguard into central Germany rather than Montgomerys 21st Army Group.

THE STRATEGIC SITUATION

The German counteroffensive in the Ardennes in December 1944 had delayed Allied plans to close on the Rhine, but at the same time the costly battles of attrition in January 1945 had decimated the Wehrmacht in the west. The German plight was further amplified by the Soviet winter offensive along the Oder River in January 1945, which forced the Wehrmacht to transfer some of its best forces, such as Sixth Panzer Army, to the east. The Soviet onslaught in Prussia and eastern Germany led Hitler to insist that the primary theater would be the east and that the Wehrmacht in the west would be limited to defensive operations. The defeat of both the Ardennes offensive and the subsequent and smaller Operation Nordwind in Alsace had made it clear, even to Hitler, that the Wehrmacht had few prospects for any military miracles in the west. As a result, in February 1945 Hitler committed his last reserves to a hopeless offensive in Hungary. The Hungarian operation was intended to relieve the besieged Budapest garrison and to serve as a springboard to strike north, trapping the Red Army with a simultaneous strike southward from East Prussia. The offensive was a costly failure and left the Wehrmacht in a perilous state with no substantial reserve of mobile forces to meet forthcoming Allied offensives, east or west.

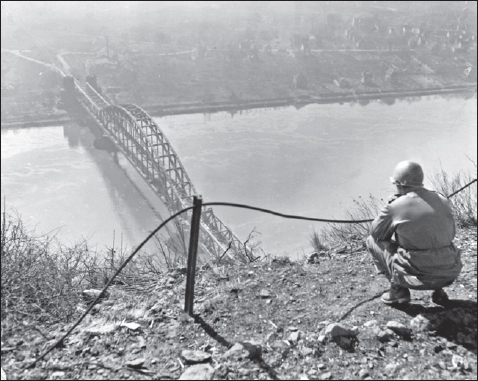

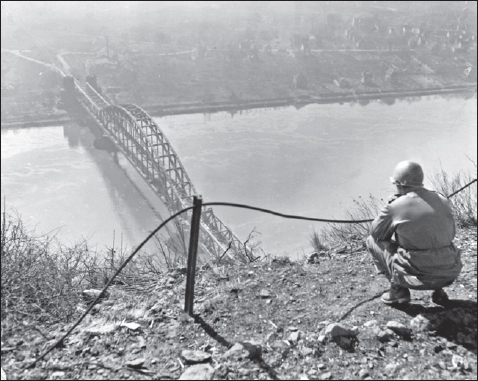

The capture of the Ludendorff railroad bridge over the Rhine at Remagen changed the dynamics of the final battles for western Germany in March and April 1945. This is a view of the bridge on March 15, 1945, from the Erpeler Ley looking westward towards the town of Remagen on the other side of the river. (NARA)

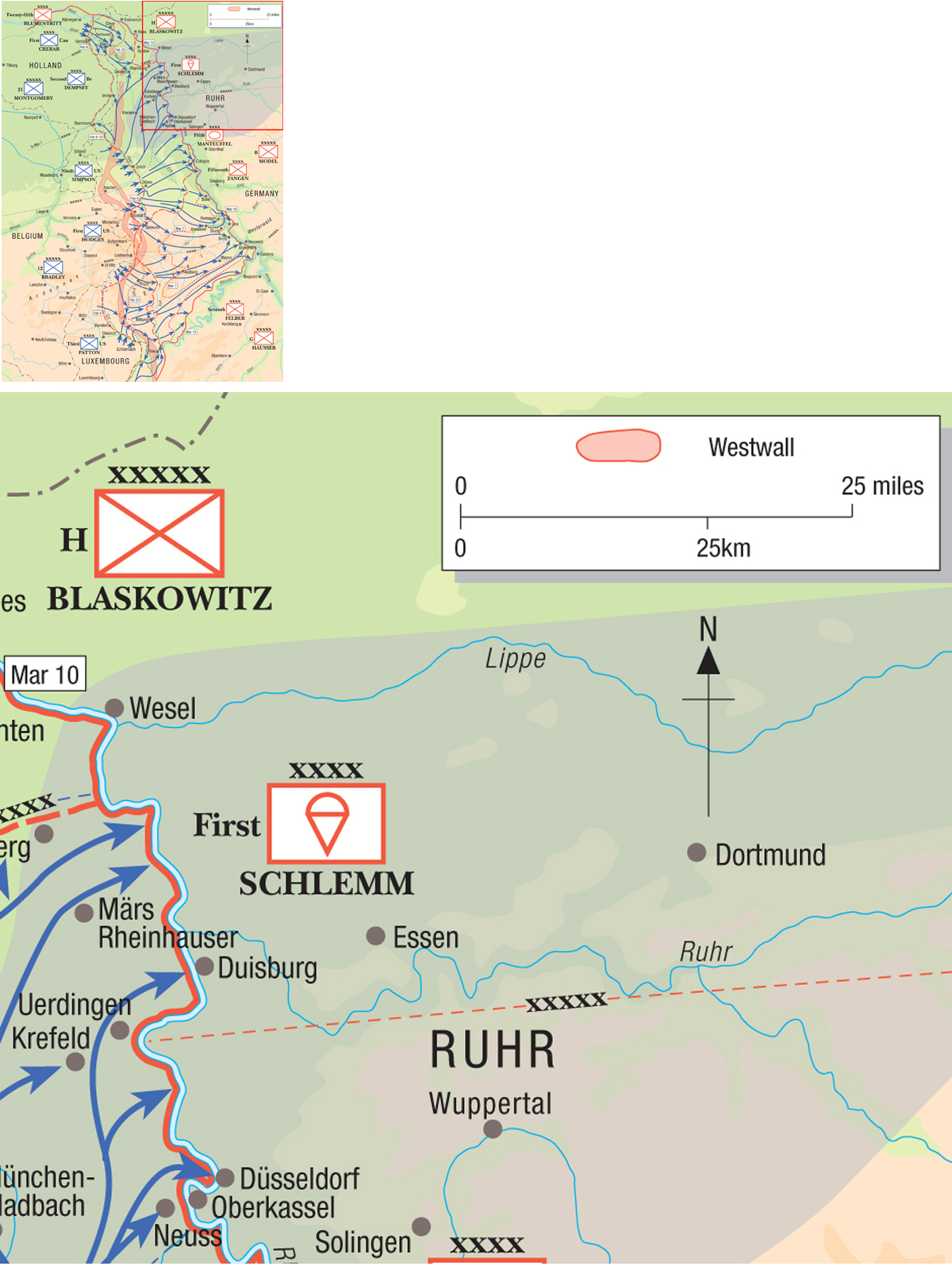

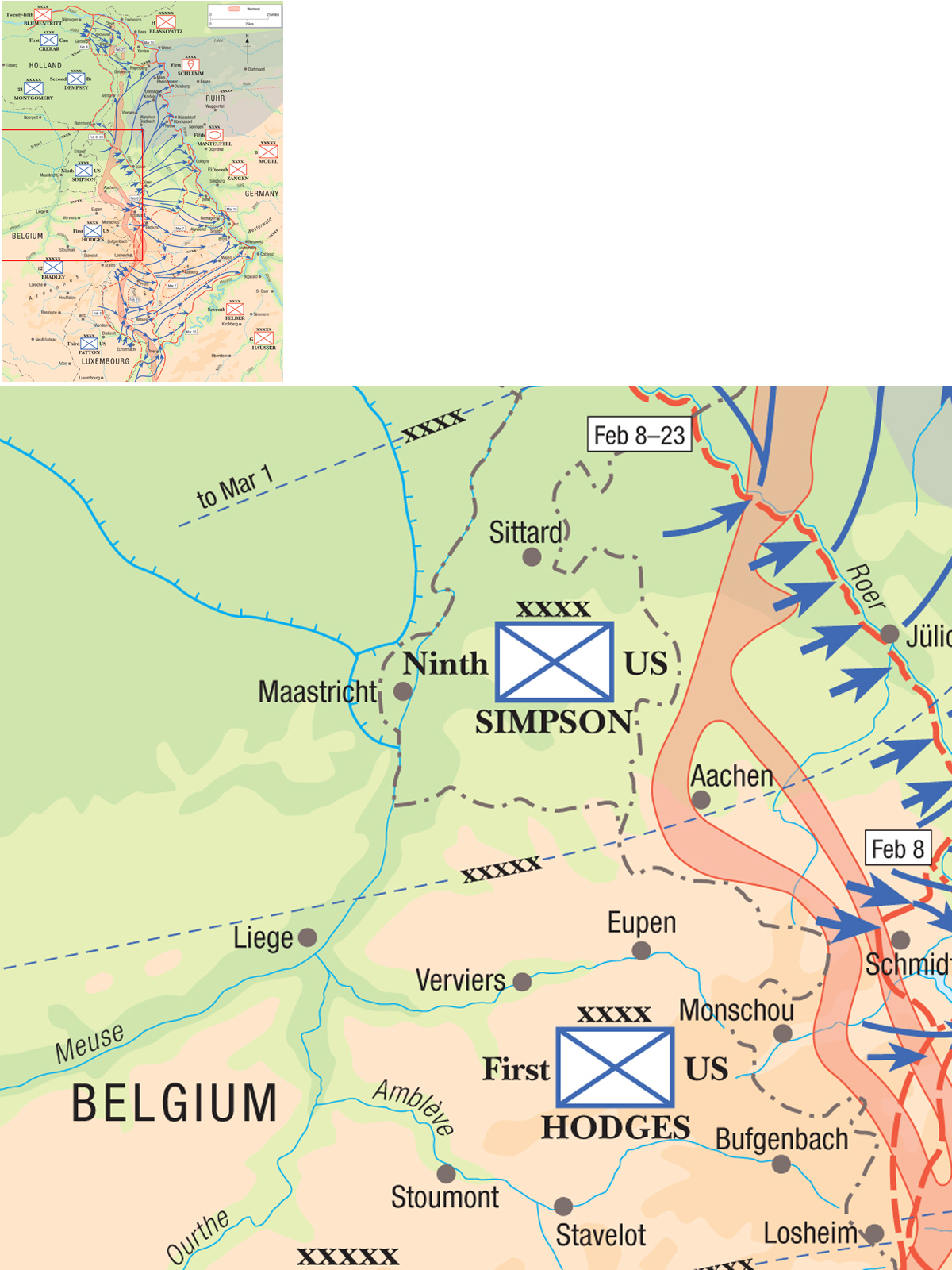

As Supreme Commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) in the west, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower had begun to clarify his plans for upcoming operations at the end of January 1945. The Rhine River was the last substantial geographic barrier to Allied entry into Germanys industrial heartland in the Ruhr and the Saar, so planning hinged around this goal. Ever since September 1944, it had been the cornerstone of Allied plans that Montgomerys 21st Army Group would be the vanguard of the Allied push into the Ruhr, first with Operation Market-Garden and, after its failure, with a Rhine-crossing operation on the northern side of the Ruhr. This strategic approach had become so widely accepted among Allied strategists that it had become known simply as The Plan. With the Rhine now within Allied grasp, Eisenhower began to fine-tune the details of how this campaign would be conducted. His intent was to conduct a three-phase operation to breach the German defenses along the Rhine. The first phase of the plan was to close on the Rhine north of Dsseldorf in anticipation of the main Rhine crossing in the sector of Montgomerys 21st Army Group. The second phase was to close on the Rhine from Dsseldorf south, in anticipation of a secondary operation by Devers 6th Army Group on the lower Rhine. The third phase would be the advance into the plains of northern Germany and into central-southern Germany once the Rhine was breached. Montgomery and the British Chiefs of Staff contested Eisenhowers plans as they favored a single thrust by Montgomerys 21st Army Group, reinforced with US corps. Eisenhower opposed this approach fearing that a single thrust offered the Germans an opportunity to concentrate their reduced resources. A secondary crossing on the lower Rhine forced the Germans to spread out their meager forces and made them more vulnerable to Allied operations. As a concession to British concerns, Eisenhowers formal proposal to the Combined Chiefs of Staff on February 2, 1945, revised the plan so that the main thrust in the north would not be held up by an effort to close on the Rhine in the other US Army sectors. In the event, the US Army was able to close on the Rhine prior to Montgomerys river-crossing operation.

The critical first step for the US First Army to reach the Rhine was to first cross the Roer River. Here, GIs of the 84th Division, part of XIII Corps, move up engineer assault boats to cross the Roer on February 23, 1945, during Operation Grenade. (NARA)

Underlying these arguments were issues of national prestige. By 1945, the British Army was a dwindling force because of manpower shortages, barely able to maintain its current order of battle in Northwest Europe. In contrast, fresh US divisions were arriving every month and by early 1945, the US Army fielded the majority of Allied divisions. Montgomery controlled the equivalent of about 21 divisions including several Canadian and one Polish division. Of the other 94 Allied divisions under Eisenhowers command, 11 were French and 62 were American. On the one hand, Montgomery attempted to guard British interests and prevent the British Army from being pushed off into a secondary mission in the final stage of the war against Germany. On the other hand, Montgomerys lack of fresh British infantry divisions forced him to ask Eisenhower to detach corps and divisions from Bradleys 12th Army Group to make up for shortages to conduct his ambitious operations. In February 1945, Montgomery was still clinging to Simpsons US Ninth Army, which had been detached to his command during the Battle of the Bulge. This transfer of troops from US to British command caused growing resentment in Bradley and other senior US commanders. But at the same time, it reduced Montgomerys bargaining power in dealing with Eisenhower who was growing increasingly weary of Montgomerys insistence on employing the 21st Army Group as the centerpiece of all major Allied offensives. During the debate over the Rhine plans, Eisenhower was taken aside by the US Army Chief of Staff, George C Marshall, and assured that the Combined Chiefs of Staff would accept his plans regardless of the complaints by the British Chief of Staff.

Next page