CAMPAIGN 231

NEZ PERCE 1877

The last fight

| ROBERT FORCZYK | ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS |

Series editor Marcus Cowper

CONTENTS

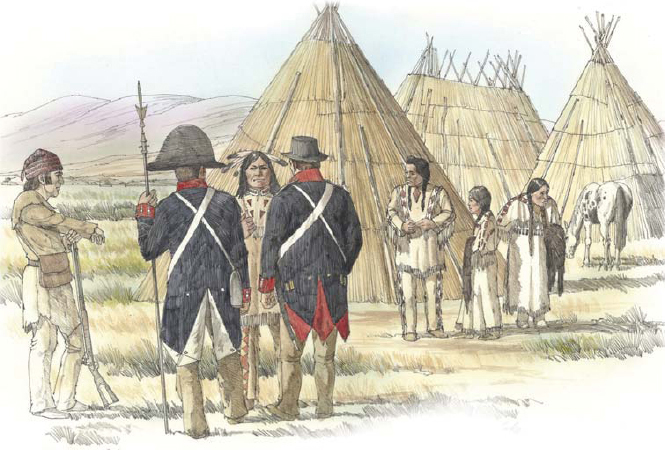

Two members of Lewis and Clarks Corps of Discovery talk with members of the Nez Perce tribe in October 1805. This first meeting between the Nez Perce and Americans went well and established a friendly relationship for the next 50 years. (Washington State Historical Society)

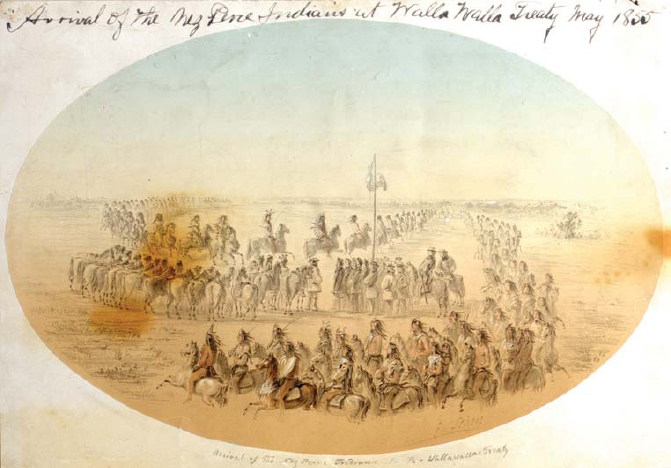

The arrival of 1,000 mounted Nez Perce warriors at the Mill Creek Council in May 1855, which resulted in the first land treaty with the US Government. When the treaty was signed, the Nez Perce were still a power to be reckoned with and were treated with a certain level of respect and probity by American representatives. However, as Nez Perce power dwindled over the next two decades, the respect evaporated. (Washington State Historical Society)

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

Nature abhors a vacuum Franois Rabelais, 1532

Hundreds of years ago, the Nimiipuu tribe settled along the Clearwater River in central Idaho, centered upon a large volcanic mound of rock known as the Heart of the Monster. Tribal traditions extend back only about three to four centuries, so it is likely that the Nimiipuu had antecedents among other tribes in the Pacific Northwest. Although the core territory held by the Nimiipuu was focused along the Clearwater River, the subsistence economy of the tribe based on salmon fishing and gathering camas roots on the Weippe Prairie forced its members to spread out to seek new food resources. Eventually, the Nimiipuu divided into sub-clans that lived in dispersed villages. These sub-clans, numbering at most a few hundred persons each, were semi-nomadic, occupying the lowland prairies in summer and then moving to the high canyons in the fall to avoid the worst of the winter snow. The Nimiipuu were also ethnically related to several nearby tribes, including the Palouse, Cayuse and the Umatilla. By the early 18th century, the Nimiipuu acquired horses from southern tribes, allowing them to send summer expeditions to the Great Plains to hunt buffalo. However, as the tribe grew in size and power, it clashed with the Shoshone tribe to the southeast and the Blackfeet to the north. The Nimiipuu, which means the real people, could be very arrogant in dealing with outsiders, which won them few allies.

In September 1805, the starving Lewis and Clark Expedition came down the Lolo Trail and encountered the Nimiipuu on the Weippe Prairie near the Clearwater River, which was the first occasion that the tribe met with Americans. Initially the Nez Perce considered killing the members of the expedition but they were dissuaded by a Nez Perce woman named Wat-Ku-ese, who claimed that other Americans had helped her escape from the Blackfeet. The Nimiipuu offered food and hospitality to the strangers because they wanted to acquire rifles, which the Shoshone and Blackfeet already possessed. Both of these enemies had inflicted losses on the Nimiipuu in recent warfare and the tribe viewed trade with the Americans as a necessity. For their part, Lewis and Clark erroneously labeled the tribe as the Nez Perce and proceeded upon their way. Within a few years, Canadian, English and American fur traders began following in the wake of Lewis and Clark, and the Nimiipuu were able to acquire flintlocks, which enabled them to fight on equal terms with the Shoshone and the Blackfeet. Soon, the Nimiipuu began a regular trade with the trappers, swapping horses for weapons and gunpowder. With their newfound firepower and mounted on fine horses, the Nimiipuu war chief Broken Arm took 45 scalps from the Shoshone and Chief Red Wolf inflicted heavy losses on the Blackfeet.

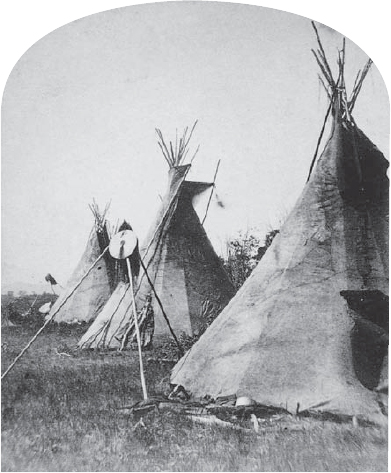

A row of Nez Perce tepees photographed near the Yellowstone River in 1871. Like most Indian tribes, the Nez Perce preferred a semi-nomadic way of life. However in failing to develop agriculture or construct fixed settlements, the Nez Perce actually made it easier to be dispossessed of their land by others, since they had no tangible signs of ownership. (Library of Congress)

For the first several decades of the 19th century, the Nimiipuu had only limited contact with Americans and it was generally friendly because it suited the tribes interests. In 1836, a group of American missionaries arrived with a fur caravan and established a school and church on the Clearwater. A number of Nimiipuu converted to Christianity, which began to alter the internal dynamics of the tribe. For decades after Lewis and Clark passed through, the Nimiipuu felt immune in their mountain strongholds to the tide of westward-moving American settlers and even the advent of the Oregon Trail in the 1840s had little immediate influence, since it passed well south of Nimiipuu lands. As long as settlers passed through and did some trading along the way, the Nimiipuu were friendly in contact with Americans. For their part, most Americans regarded the Nez Perce as one of the few friendly tribes in the Pacific Northwest. In November 1847, members of the neighboring Cayuse tribe murdered 14 American missionaries in the Whitman Massacre, which precipitated eight years of sporadic conflict known as the Cayuse War. Rather than supporting their kinsmen, the Nimiipuu remained loyal to the Americans and did not lift a finger to help the Cayuse.

As a result of the lawlessness evidenced by the Whitman Massacre, the Oregon Territory was created and at least part of the Nimiipuu lands fell under the nominal jurisdiction of the US Government. After the Cayuse were finally defeated in 1855, the governor of the Oregon Territory sought to delineate tribal lands from lands open to settlement in order to reduce the risk of further conflict. A great council was called at Mill Creek near Walla Walla in May 1855 to hammer out a series of treaties between Oregon acting as a proxy for the US Government and the local tribes. The defeated Cayuse and the restive Umatillas were treated harshly, losing much of their lands and being forced onto small reservations. Although the Nez Perce were enjoined to sign a treaty as well, because of their help in the Cayuse War they were not required to involuntarily relinquish any land, although settlers could purchase land with their consent. The conversion of large numbers of Nez Perce to Christianity also predisposed the governor of Oregon to use the carrot rather than the stick with them, promising cash and trade gifts. Despite the fact that the governor lacked the military power to force Old Joseph, Looking Glass and other Nimiipuu leaders to sign the treaty, they did so anyway. When the dispossessed Cayuse, Yakima and other tribes resisted resettlement and murdered American miners shortly after the treaty was signed, beginning the Yakima War, the Nez Perce again sided with the Americans and provided 30 scouts to the US Army.

The Treaty of 1855 seemed to safeguard Nimiipuu interests but it caused a rift with neighboring tribes who lost land as a result. The Nimiipuu were living well on their own lands, enjoying a profitable trade with American merchants, but their potential allies were defeated piecemeal by American military forces or marginalized on reservations. Gradually, Nez Perce lands were becoming surrounded by American settlements. The Oregon Territory was reorganized with the creation of the Washington Territory in 1853 and then Oregon became a state in 1859. By 1860, there were over 60,000 American settlers bordering the 12,000 square miles (31,000 square kilometers) of territory held by only 3,000 Nez Perce, which created pressure for expansion onto the lands reserved by the Treaty of 1855. Complacent with their gifts and pledges of protection, the Nimiipuu leadership was only vaguely aware that the correlation of forces was shifting against them.