History is but a tapestry of stories, imperfectly woven.

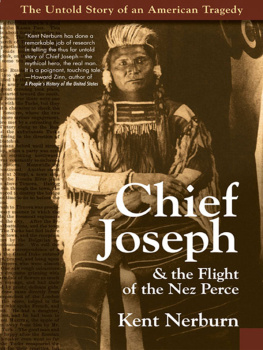

O N NOVEMBER 20, 1903, a tired, stoop-shouldered man with chestnut brown skin stood on the sidelines of a football game at the University of Washington in Seattle. He understood little of what was going on, but he followed the action with keen interest, enjoying the efforts of the young men and nodding approvingly whenever the ball carrier emerged unscathed from the pile of bodies after a tackle. His presence at the game so fascinated the other spectators that they seemed almost as interested in him as they did in the game itself.

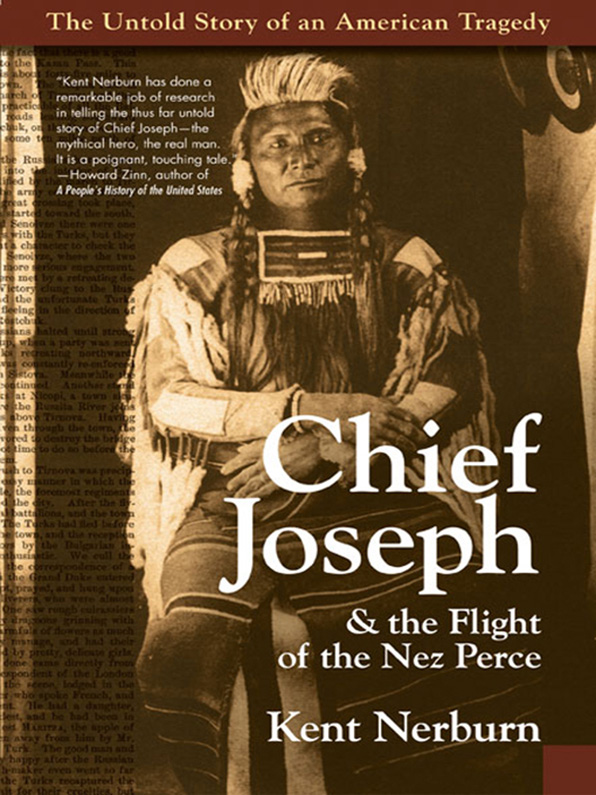

This man, so seemingly engrossed in a game about which he understood little, was a sixty-three-year-old Nez Perce Indian named Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekht, or Thunder Rising in the Mountains. But to the American public he was known as Chief Joseph, the Red Napoleon, the man who was reputed to have masterminded one of the most cunning military retreats in American history and to have outfoxed and outmaneuvered the best that the American army had to offer. He was Americas greatest living Indian celebrity.

Joseph had come to Seattle at the request of Sam Hill, son-in-law of the railroad magnate James J. Hill, to give a speech in the Seattle Theater. It was but one speech of many he had given around the country over the previous decade in an effort to gain the return of his small band of Nez Perce to their homeland in the high Wallowa Valley in the mountains of eastern Oregon.

As at all his speeches, Josephs Seattle appearance was a great civic eventa chance to see the man Buffalo Bill Cody called the greatest Indian America ever produced and whom photographer Edward Curtis praised as one of the greatest men who ever lived. The auditorium was packed and the press and local dignitaries were in full attendance.

Most had heard of his previous speeches, in which he had recounted how his people had been forced to leave their land as part of a treaty his band had never signed; of the great exodus they had undertaken across the mountains of Idaho and Montana in search of freedom; of the sad exile they had endured in Kansas and Oklahoma; and of their continued exile on land not their own in the northeastern part of Washington on the Canadian border.

They had heard of his eloquent pleas for just treatment by the government, asking only that his people be treated as free men and womenfree to travel, free to trade, free to talk and act and worship in accordance with their own conscience; his almost prayerful petition that the spirit of brotherhood might wash away the bloodstains that soaked the earth, that all people might live as one, smiled upon by the Creator, common children of a common land, living together beneath a common sky.

They sat in rapt anticipation, waiting for the legendary Indian leader to emerge and galvanize them with his rhetoric.

But the person who took the stage seemed anything but a noble orator. He was a worn and weary man, bent and bowlegged, dressed in full headdress and traditional chieftain regalia. He seemed more tragic than noble, more anachronistic than imposing.

Taking a drink from a glass of water and leaning heavily against a table, he began to speak, his words translated instantly by the interpreter who accompanied him. I have a kind feeling in my heart for all of you, he said. I am getting old and for some years past have made several efforts to be returned to my old home in Wallowa Valley, but without success.

The government at Washington has always given me many flattering promises, he continued, but up to the present time has utterly failed to fulfill any of its promises. He told of how he was not surprised because his life had been filled with broken promises, and of his dream to be buried by the side of his father and children.

I hope you will all help me to return to the home of my childhood where my relatives and family are resting, he concluded. Please assist me. I am thankful for your kind attention. That is all. Then he sat down.

The audience was respectful, even touched. But they were also stunned. This was not the speaker they had been led to expect, the man who had been favorably compared to the great orators of the Roman senate. The local paper even mocked his presentation, recreating his Indian language as Um-mum-mum-halo-tum-tum-um-mum and describing his appearance as looking like a turkey cock on dress parade. They characterized his speech as grunts and implied that any meaning in the words had likely been invented by the translator.

The chief accepted all this with equanimity. He was used to both the adulation and vilification of the white public and government. But none of that was important to him. All he cared about was the fragile hope that he and his people someday would be allowed to return to their beloved Wallowa, the land that the Creator had given them and the earth that held their ancestors bones.

He remained several more days in Seattle, signing autographs, posing for photographs, and visiting the University of Washington. Then he quietly returned to his home on the Colville Reservation, 350 miles from the city where he had just spoken and 200 miles from the Wallowa, where he hoped to spend his final days.

He lived on for less than a year, passing away quietly on September 21, 1904.

The agency doctor, who attended him in his illness, declared simply that the chief had succumbed to a grief which ended in death.

He was never allowed to return to his homeland.

Josephs story, and the story of the Nez Perce, has become part of the standard lore of the American Indian. Its outline has been presented to students by caring teachers and professors for years: Joseph, the Nez Perce chief, led 800 men, women, and children on a 1500-mile retreat after having been illegally forced from their homeland in Oregon by a U.S. government that was hungry for land and unwilling to meet its treaty obligations.

In the course of this journey they outmaneuvered five U.S. armies, assisted white travelers they met along the way, and managed to elude the best and brightest that the U.S. military had to offer. Finally, only forty miles from the Canadian border and freedom, the tired Nez Perce, slowed by their wounded and weary, were surrounded by the U.S. forces. They could have escaped by leaving the women and children and injured and elderly behind, but this Joseph was unwilling to do. Wrapping his blanket around his shoulders against the frigid winds of an approaching high plains Montana winter, he walked across the snow-swept battlefield and handed his rifle to the commanding officers of the U.S. military, speaking that now-famous sentence: From where the sun now stands, I shall fight no more forever.

A fine story, full of pathos and nobility and all the poignancy of the American Indian struggle. A fine story, but false. Or, to be more accurate, only half true.

The real story, the true story, is every bit as poignant and every bit as dramatic. But it is obscured by the myth because the myth is so powerful and so perfectly suited to our American need to find nobility rather than tragedy in our past. It is also a myth of our own devise, and therein lies a story.

I first encountered the story of Chief Joseph fifteen years ago when I was working on the Red Lake Indian Reservation in the woods of northern Minnesota. I had been hired to lead a group of students in collecting the memories of the tribal elders.