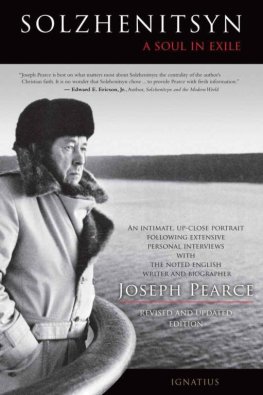

SOLZHENITSYN

JOSEPH PEARCE

SOLZHENITSYN

A SOUL IN EXILE

Revised and Updated Edition

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Original edition published in 1999 by HarperCollins Publishers, Ltd.

1999 by Joseph Pearce

Second edition published in 2001 by Baker Books, Grand Rapids, Michigan

Cover photograph:

Solzhenitsyn

February 26, 1974 Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Except as otherwise stated,

all interior photographs supplied to the author by

Natalya Dmitrievna Solzhenitsyn

Cover design: Roxanne Mei Lum

2011 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-496-5

Library of Congress Control Number 2010931420

Printed in the United States of America

FOR AIDAN AND DORENE MACKEY

IN GRATITUDE AND FRIENDSHIP

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, I must acknowledge a debt of gratitude to the subject of this book. Without the full and generous cooperation of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, my efforts would have floundered in an ocean of secondary sources. That is not to say that I have not made use of an extensive array of such sources. I have, of course, and the principal published sources have been acknowledged in the Notes, but without Solzhenitsyns personal involvement I would not have had the benefit of the insight into his life and work that, I hope and trust, is conveyed in this volume. I am acutely conscious of the privileged nature of my access, not least because of the Russian writers well-known distrust of Western biographers and journalists, and this only serves to accentuate my feelings of gratitude. I am mindful, for instance, that a previous biographer met with no success whatsoever in securing Solzhenitsyns aid, to the extent that even his letters were not answered. (It was a tribute to that particular biographers powers as a writer that the book he produced was still of exceptional quality.) I dont know why Solzhenitsyn broke his boycott of Western writers in my case, and this is not the place to conjecture, but I am nonetheless delighted to be the beneficiary of his assistance.

During my visit to Russia, I was the recipient of Alya Solzhenitsyns warm hospitality as well as being the eager and hungry recipient of her traditional Russian cuisine. Subsequently, she has helped me considerably with details of her own life and that of her husband. I am grateful also to Yermolai Solzhenitsyn, not only for his patient and grueling work as simultaneous translator during the interview with his father, but also for the impromptu guided tour of Moscow which followed. Yermolai continued to help me in the following months, replying to my questions at length and sharing his childhood memories of life in Vermont and in England, and his impressions of his fathers return to Russia and subsequent reception by the Russian people.

Ignat Solzhenitsyn, Yermolais brother, was tireless in his assistance throughout the months that the book was in preparation. In spite of his own busy schedule in the United States, where he is a highly accomplished and much sought-after concert pianist, he never failed to respond to my pleas for help, replying by phone, fax, e-mail, and even, on occasion, by the old-fashioned postal service. Without his help in arranging my visit to Moscow, in acting as go-between and translator for his father and mother, and in offering his own memories and opinions, this biography would scarcely have been possible. I am, indeed, deeply indebted.

This new, revised edition has been the beneficiary of Ignat Solzhenitsyns translations of several Russian sources into English, and is enriched by recent photographs supplied by Natalya Solzhenitsyn. Apart from my indebtedness to Mrs. Solzhenitsyn for her generosity in supplying these new photographs, I am also grateful to Ignat and Stephan Solzhenitsyn for their assistance in getting them to me expeditiously, via cyber-space, in time for their inclusion.

I am grateful to Michael Nicholson for the help he has given me during the writing and researching of the book, both at University College, Oxford, and during numerous telephone conversations. He was also kind enough to translate twenty-four lines of Solzhenitsyns verse from the Russian edition of The Gulag Archipelago , volume two.

I must express my thanks to Sarah Hollingsworth for her invaluable critical appraisal of the original manuscript; to the late Alfred Simmonds for his tireless encouragement; to Katrina White for help with translation; and to James Catford, Elspeth Taylor, and Kathy Dyke at HarperCollins UK, who labored to bring the original edition of this work to fruition. In similar vein, I owe a debt of gratitude to Father Joseph Fessio, Mark Brumley, Tony Ryan, Carolyn Lemon, Diane Eriksen, and the rest of the people at Ignatius Press for their work on this second and revised edition.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

My meeting with Alexander Solzhenitsyn at his home in Moscow in 1998 ranks as perhaps the greatest honor of my life. At the time, the great Russian writer and Nobel Prize winner was approaching his eightieth birthday. My biography, therefore, was a timely tribute to a life well-lived, a life of courage in the face of tyranny, a life of true heroism. It was, however, a life that was still being lived, a life that still had a good deal of life in it. Solzhenitsyn would live for a further ten years, a full decade, in which he resolutely refused to retire and in which he remained a controversial figure in Russia, and indeed throughout the world.

Since Solzhenitsyns life was far from finished when I wrote about it, my life of him was also, ipso facto, an unfinished work. This second edition is, therefore, the final version of a biography of which the first edition was only a precursor. Containing four additional chapters and some important revisions, the present volume offers a panoramic perspective of the whole of Solzhenitsyns life, all eighty-nine years of it, and a testimony and tribute to his achievement and his legacy.

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION

If any twentieth-century literary figure has been the victim of media typecasting, it is Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Whenever his name is mentioned, it is almost invariably accompanied by the same stereotypical characterization. He is, we are reliably informed, a prophet of doom, an arch-pessimist, a stern Jeremiah-like figure who is out of touch, out of date, and, worst of all in our novelty-crazed sub-culture, out of fashion. He is also, we are told, irrelevant to the modern world in general and modern Russia in particular.

Perhaps this attitude to the Russian Nobel Prize winner was epitomized by George Trefgarne in an article entitled Solzhenitsyn Loses the Russian Plot in the business section of the Daily Telegraph on June 6, 1998. Alexander Solzhenitsyn proved again that he is never happier than when he is thoroughly miserable, Trefgarne wrote. His impassioned critique of the new Russia displays the sense of doom, disaster and history you would expect from a survivor of the Soviet Union and a Nobel prizewinner. Solzhenitsyn believes Russia has overthrown the evils of communism only to replace them with the evils of capitalism.

Mr. Trefgarnes article ended with the statement: Alexander Solzhenitsyn is a better writer than he is an economist. Yet why, one is tempted to ask, should this disqualify the writer from commenting on his countrys problems? Did Dickens have nothing of importance to say about the squalor of Victorian England? Did George Orwell have nothing to say about the dangers of totalitarianism? Compared with the literary light which these writers were able to throw on controversial issues, the weakness of much of the analysis in the business sections of newspapers is only too apparent. Indeed, Mr. Trefgarnes own article was a case in point. He stated that Solzhenitsyn and the doom-mongers could have exaggerated their case because the new and dynamic Russian prime minister, Sergei Kiriyenko, was revitalizing the ailing Russian economy with a decisive package of measures. With an ingenious use of statistical data, Trefgarne xii painted a rose-tinted picture of Russias future, which reminded one of Solzhenitsyns complaints that his countrys troubles were forever being covered up... by mendacious statistics.

Next page