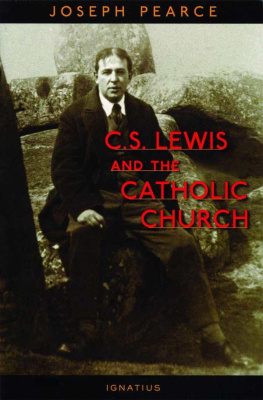

C. S. LEWIS AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

JOSEPH PEARCE

C. S. LEWIS

AND THE

CATHOLIC CHURCH

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover photograph:

C. S. Lewis at Stonehenge in 1925

Copyright Marion Wade Center

Wheaton College, Wheaton, Illinois

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

2003 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 0-89870-979-2

Library of Congress Control Number 2003105167

Printed in the United States of America

FOR

WALTER HOOPER

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

The question of C. S. Lewiss churchmanship is a question that wont go away. When he billed himself, in the 1940s, as a mere Christian, it seemed a stroke of genius. Yes. Why not have an apologia for the ancient Faith that avoids all partisan matters, and lays out for the unbeliever (and for the believer too, for that matter) the nature of Christian belief, and the reasoning underlying that corpus of belief? Certainly the success of Lewiss apologetic work would seem to testify to the wisdom of the approach that he chose. How many people (millions?) would give Lewis the credit for having assisted them along to true, regenerating Christian faith? Is it pettifogging, then, to raise, forty years after Lewiss death, the question of his particular churchmanship? Can we not simply leave it where he wished to leave it? He never tried to hide his Anglicanism; but he never wanted to give his description of the Faith any remotest Anglican tint. Surely this is praiseworthy?

Indeed But difficulties do arise. Lewis wished to leave on one side various peripheral topics. But what if those topics are not peripheral to the most immense, most ancient, body of Christians? The nature of the Eucharist (and of all of the Sacraments, actually); and the role of the Blessed Virgin in the drama of Redemption; and the sacerdotal, apostolic priesthood; and the office of Peter; and the Communion of the Saints; and the doctrine of Purgatorythese can be called peripheral only by an avowed partisan, namely, a Protestant. And Protestantism is a late-comer to the Christian scene So There is an anomaly here: Lewis wishes us to accept his identity as a mere Christian; but we find that the truth of the matter is that he was a mere Protestant. Quite ferociously so, as it happens. His Ulster background colored his attitudes more garishly than he, in his coldly rational moments, might have wished to admit. (He is furious, for example, when a Catholic publisher of one of his books seems to want to market it to Dublin riff-raff)

But there are more anomalies. Although he loathed the whole business of High, Broad, and Low churchmanship in the Church of England, he could not avoid it all. He had nothing but contempt for the Broad churchmen who diluted the Faith until it was a mere sickly gruel (see his Anglican bishop in The Great Divorce ). And he detested the smells and bells, lace-cotta, biretta sort of thing that one finds at Anglo-Catholic shrines, and which formed the metier of T. S. Eliot. He just wanted to be left alone, to go to church and be done with it.

But it was not so simple. In spite of himself, Lewis moved more and more toward what can only be called a catholic Anglicanism. Againhe hated the epicene punctilio of the Anglo-Catholic party : but his faith came to embrace all sorts of doctrines and practices that his evangelical readers (who are his most enthusiastic clientele) must sedulously ignore. He spoke of the Blessed Virgin, and made his confession to his priest regularly, and believed in purgatory, and even came to refer to the Eucharist asheaven help us all the Mass!

Lewiss anti-Romanism remained with him until his death, however. The point of a book like this is not to quibble. Joseph Pearce is one of Lewiss strong allies. But Lewiss public will find here, I think, an enormous amount of material that is both fascinating andit must be admittedgermane.

Thomas Howard

Manchester, Massachusetts

INTRODUCTION

If one desires a thumbnail sketch of C. S. Lewiss attitude toward the centuries-old conflict between Protestants and Catholics, one might reflect on the pair of epigraphs by which he chose to introduce The Screwtape Letters .

The best way to drive out the devil, if he will not yield to texts of Scripture, is to jeer and flout him, for he cannot bear scorn. Luther

The devil the prowde spirit... cannot endure to be mocked.

Thomas More

Both quotations say basically the same thing; to paraphrase Saint Paul, Laugh at the devil, and he will flee from you. Aside from this extraordinary advice, what is remarkable about Lewiss choice of epigraphs is the identity of the two authors. Not only is Luther a Protestant and More a Catholic, but these two men are also accounted champions of their respective parties, each having fought fearlessly for his own position. What is more, many of their fiercest confrontations were fought against one another, often in scathing letters and treatises. That Lewis, himself an Anglican, should choose these two voices for his epigraph creates an unmistakable impression. Here stand side by side two men, a Protestant and a Catholic, who opposed one another relentlessly during their earthly Eves, seeming now to speak with one reassuring voice, folded in a single party. The fact that both voices recommend laughter at the absurdity of evil is a testament to a conviction, seen elsewhere in Lewiss works, that the Christian perspective of comedy, in both the lighthearted and in the cosmic sense, will in the end win out over the tragic divisions that have historically beset the Body of Christ on earth.

This harmonious juxtaposition of Luther and More may say more about Lewiss approach to the Protestant / Catholic question than most of his explicit comments, which are indeed sparse. Not only does he seem here to desire reunion, but he also suggests that a kind of union already exists beneath the surface even of bitter disunion. Lewis was no stranger to such bitterness, having been raised in Protestant Belfast amid acrimonious conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. His reasons for avoiding open discussions of the question, as the present book makes clear, can be partly explained through an understanding of his formative years in Protestant Ulster.

Although Lewis did for the most part manage to avoid openly discussing the Protestant / Catholic question throughout most of his life, the question did not always avoid him. When his autobiographical allegory The Pilgrims Regress was published in 1933, its richly traditional imagery and sacramental plot line caused many people in Oxford to speculate that Lewis had in fact already become a Catholic. In a sense, the question of his relation to Catholicism would haunt him for the rest of his days. By 1952, when Mere Christianity was first published as a book, Lewis had grown so sensitive to questions about his denominational stance that he wrote a Preface in which he confesses up-front to being an Anglican, and then proceeds very carefully and at some length to defend his unbroken silence on these matters throughout the rest of the book.

His stated reasons for avoiding ecclesiastical controversies in Mere Christianity are simple. He says, first of all, that he is a mere layman, and that he is not qualified to navigate such deep waters. Second, he says that he has avoided discussing such disputes precisely because they have no tendency at all to bring an outsider into the Christian fold. So long as we write and talk about them we are much more likely to deter him from entering any Christian communion than to draw him into our own.

In some ways, Lewiss project has been doubly successful. Legions of nonbelievers have testified to being brought to faith in Christ by reading the works of C. S. Lewis. In addition, however, Lewiss works have also resonated profoundly within the global Christian fold as well. Father Joseph Fessio, S.J., has commented on the striking phenomenon of Lewiss universal appeal to Christians worldwide, which was considerable in Lewiss own day, and which has only grown since his death in 1963. Father Fessio made these remarks during a theological conference in the mid-1990s, which Peter Kreeft recalled in 1998 as the most memorable moment of the most memorable conference I ever attended. Attending the meeting, says Kreeft, were dozens of high-octane Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Eastern Orthodox and Protestant Evangelicals, who, despite their noted theological differences, converged near the end of the conference in a crescendo of agreement. Kreeft continues:

Next page