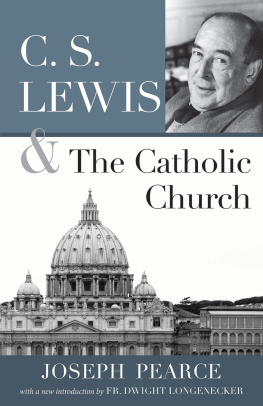

Copyright 2013 Joseph Pearce

All rights reserved. With the exception of short excerpts used in articles and critical review, no part of this work may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in any form whatsoever, printed or electronic, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book was first published in the United States by Ignatius Press in 2003. This Saint Benedict Press edition has been re-typeset and revised. Revisions include occasional spelling, punctuation, and typography corrections. This edition also includes a new introduction by Fr. Dwight D. Longenecker, and a new appendix by the author.

Typeset by Lapiz.

Cover design by Caroline Kiser.

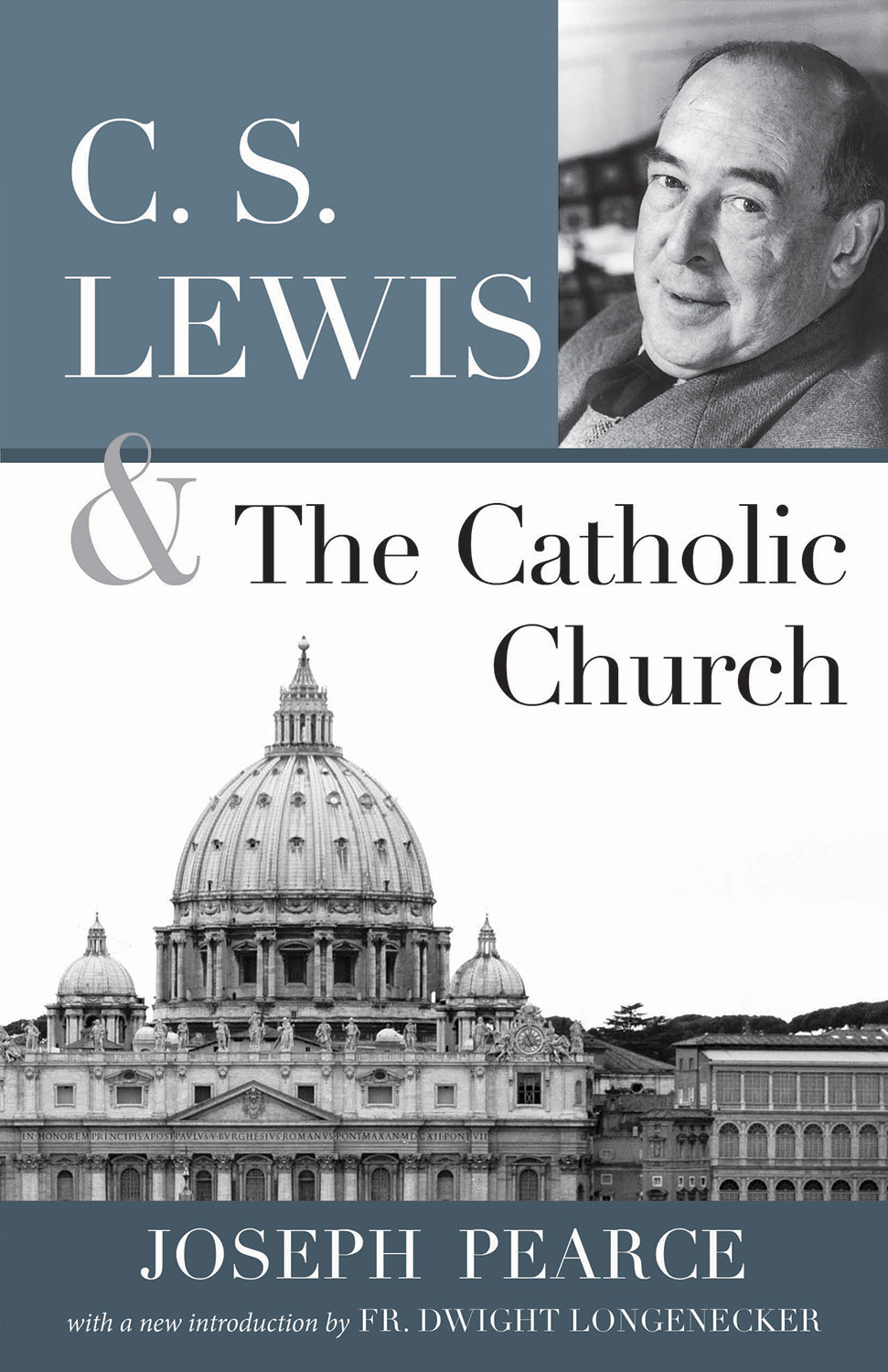

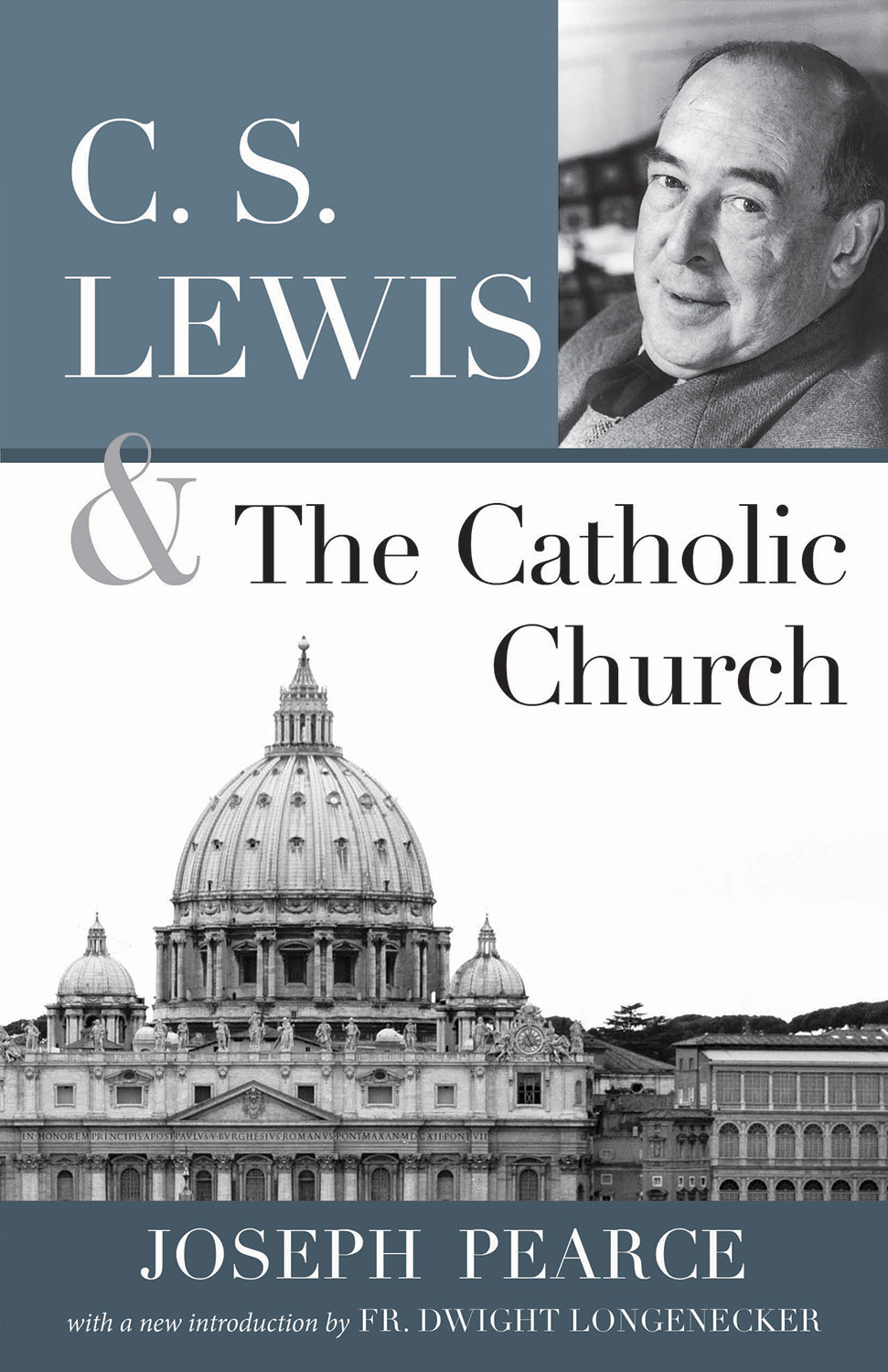

Cover images: St. Peters Basilica iStockphoto.com/ToniFlap . Portrait of C. S. Lewis (18981963), United Kingdom, 1958. (Photo by Wolf Suschitzky/Pix Inc./Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images).

ISBN: 978-1-61890-230-6

Published in the United States by Saint Benedict Press, LLC PO Box 410487 Charlotte, NC 28241 www.SaintBenedictPress.com

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

for

WALTER HOOPER

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

T HE QUESTION of C. S. Lewiss churchmanship is a question that wont go away. When he billed himself, in the 1940s, as a mere Christian, it seemed a stroke of genius. Yes. Why not have an apologia for the ancient Faith that avoids all partisan matters, and lays out for the unbeliever (and for the believer too, for that matter) the nature of Christian belief, and the reasoning underlying that corpus of belief? Certainly the success of Lewiss apologetic work would seem to testify to the wisdom of the approach that he chose. How many people (millions?) would give Lewis the credit for having assisted them along to true, regenerating Christian faith?

Is it pettifogging, then, to raise, forty years after Lewiss death, the question of his particular churchmanship? Can we not simply leave it where he wished to leave it? He never tried to hide his Anglicanism; but he never wanted to give his description of the Faith any remotest Anglican tint. Surely this is praiseworthy?

Indeed. But difficulties do arise. Lewis wished to leave on one side various peripheral topics. But what if those topics are not peripheral to the most immense, most ancient, body of Christians? The nature of the Eucharist (and of all of the Sacraments, actually); and the role of the Blessed Virgin in the drama of Redemption; and the sacerdotal, apostolic priesthood; and the office of Peter; and the Communion of the Saints; and the doctrine of Purgatorythese can be called peripheral only by an avowed partisan, namely, a Protestant. And Protestantism is a late-comer to the Christian scene. So. There is an anomaly here: Lewis wishes us to accept his identity as a mere Christian; but we find that the truth of the matter is that he was a mere Protestant. Quite ferociously so, as it happens. His Ulster background colored his attitudes more garishly than he, in his coldly rational moments, might have wished to admit. (He is furious, for example, when a Catholic publisher of one of his books seems to want to market it to Dublin riff-raff.)

But there are more anomalies. Although he loathed the whole business of High, Broad, and Low churchmanship in the Church of England, he could not avoid it all. He had nothing but contempt for the Broad churchmen who diluted the Faith until it was a mere sickly gruel (see his Anglican bishop in The Great Divorce). And he detested the smells and bells, lace-cotta, biretta sort of thing that one finds at Anglo-Catholic shrines, and which formed the mtier of T. S. Eliot. He just wanted to be left alone, to go to church and be done with it.

But it was not so simple. In spite of himself, Lewis moved more and more toward what can only be called a catholic Anglicanism. Againhe hated the epicene punctilio of the Anglo-Catholic party: but his faith came to embrace all sorts of doctrines and practices that his evangelical readers (who are his most enthusiastic clientele) must sedulously ignore. He spoke of the Blessed Virgin, and made his confession to his priest regularly, and believed in purgatory, and even came to refer to the Eucharist asheaven help us all the Mass!

Lewiss anti-Romanism remained with him until his death, however. The point of a book like this is not to quibble. Joseph Pearce is one of Lewiss strong allies. But Lewiss public will find here, I think, an enormous amount of material that is both fascinating andit must be admittedgermane.

Thomas Howard

Manchester, Massachusetts

INTRODUCTION

A SERIOUS CASE OF ANGLO-PHILIA

A S AN American college student in the late 1970s I was afflicted with a severe case of a dangerous disease called Anglo-philiathe love of all things Englishand C. S. Lewis was largely to blame. I had been brought up in an Evangelical Fundamentalist family, and after high school I visited England while on a mission trip to Europe.

I was captivated by the robust life of London, the wry humor of the people, the quaint antiquity of English villages, the living links to the literary history, and the mellow beauty of the countryside. I arrived home and said to my parents, Im going to live over there one day!

The Protestant religion in our home was a quiet, sincere, and deep faith. Our Christianity was the old, old story of a human race lost in sin and the saving love of God who sent his son for our redemption. We were fervent believers, but our faith was not fiery. After high school, however, I attended Bob Jones University (the fundamentalist college in South Carolina), and there the temperature of the religion was rather warmer.

Dr. Bob Jones preached against the Catholic Church which was the great whore of Babylon. Liberals were the enemy, the seminarian preacher boys were ready to roll, and hell was real. This rip snortin religion wasnt for me. I had already imbibed deeply of English culture and as a Speech and English major I went further up and further in. I was discovering a form of Christianity which was deeper, broader, and more ancient than anything I had met with before. The problem was that fundamentalists considered this other Christianity of the mainline Protestant denominations to be liberal and worldly. We were taught how modernism had infected the Protestant churches and that they were not to be trusted. In the midst of these intellectually stormy waters, C. S. Lewis threw me a lifeline.

Lewis provided a bridge between the historic, Biblical Christianity I had been taught as a boy and the real roots of that faith in the European tradition. Lewiss writings were orthodox and acceptable but they were also intelligent, witty, and fresh. He upheld something he called Mere Christianity which was the basic, Biblical historic Christian faith. That was what I believed, and yet Lewis was clearly not a fundamentalist, Southern Baptist. What religion was he? Like T. S. Eliot, George Herbert, John Donne, and others it turned out that Lewis was a member of the Church of England, and that he believed it was possible to be a mere Christian within the Anglican Church.

I was delighted to find that an Anglican church existed in Greenville, South Carolina, and that we were permitted to go there. So with some other students I started attending the little stone church in the bad part of town, and was immediately taken with the Book of Common Prayer, lighting candles, singing decent hymns, and kneeling to pray. This was C. S. Lewiss church! Someone gave me a picture book called C. S. Lewis : Images of His World. It was full of photographs of golden green Oxford quadrangles and people punting on the River Cam. There were pictures of Lewis and the Inklings smoking pipes and swilling beer in cosy English pubs. The book was all misty fields, quiet English rivers, the hobbiton-like hills of rural England, the heavenly glories of Cambridge chapels, and the homely glories of country churches.

Next page