The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde

JOSEPH PEARCE

The Unmasking of

Oscar Wilde

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Original edition published by

HarperCollins, London

2000 by Joseph Pearce

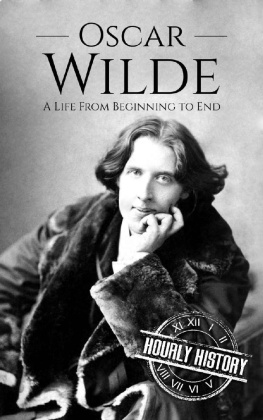

Front jacket photograph of Oscar Wilde

reproduced courtesy of the V&A Picture Library

2004 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 1-58617-026-0

Library of Congress control number 2003115828

Printed in the United States of America

For Derek and Jo Barrel

You knew what my Art was to me,

the great primal note by which I had revealed,

first myself to myself, and then myself to the world;

the real passion of my life;

the love to which all other loves

were as marsh-water to red wine.

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

My motives for writing this life of Wilde are enumerated in the Preface to the first edition, which was published in the UK in 2000 by HarperCollins on the centenary of Wildes death. This second edition, published on the 150th anniversary of Wildes birth, signals its first publication in the United States. I am grateful, therefore, to Ignatius Press for making The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde available to a much larger readership on this side of the Atlantic.

Although, as I say, I have given my reasons for writing the book in the original Preface, to which I now refer the readers attention, I would like to make a few additional comments on the occasion of the publication of the first American edition.

Principally I would like to reiterate the overriding fact that Wilde remains an enigma. The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde is an attempt to get to grips with that enigma; it is an endeavour to solve the mystery that Wilde projects. It is nothing less than a quest for the Real Oscar. Thus, as the title suggests, I have sought to strip away the masks that Wilde wore throughout his lifeand the masks that others have placed on him since his death.

Have I succeeded in this quest? Perhaps that is for the reader to decide. For my part, however, I am convinced that The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde penetrates to the very core of its subject. After peeling away layer after layer of artificial accretion we find the artful secretion of his deepest feelings, secreted away behind the masks of his public persona but revealed beguilingly in and through his art. As Wilde expressed it in The Ballad of Reading Gaol:

How else but through a broken heart

May Lord Christ enter in.

The following work is a journey to the centre of a broken heart.

PREFACE

Oscar Wilde died a pariah. He was scorned by the world and was ostracized by all except a loyal handful of friends. Today, a hundred years after his poverty-stricken death, he is the adored and idolized icon of a growing cult. In the past few years any item of memorabilia connected with him has been sold for large sums at auction. A questionnaire filled in by Wilde when he was at Oxford sold for 23,000;an inscribed cigarette case apparently given to Wilde by Lord Alfred Douglas sold for 14,000 despite its doubtful authenticity; and two letters from Wilde to Philip Griffiths, described as one of his lovers, reached 16,000 at Christies. The letters were themselves innocuous and there is no evidence that Wilde ever had a sexual relationship with Griffiths, but the letters sold nonetheless. Wildes grandson, Merlin Holland, expressed a sense of exasperation at the cult surrounding his grandfather but added philosophically that he could appreciate the humour of questionable pieces of memorabilia from Saint Oscar the Sinner being offered to a credulous public at absurd prices and be proud of my ancestors ability to take his revenge a century later.

The irony of the present situation is that Wilde is remembered far more for his private life than for his art. It is not a state of affairs that would have pleased him. In fact, it would have horrified him. He would have seen it as the last and worst insult to his battered reputation. For Wilde, art was always Art and it was by this alone that he desired to be judged, both by his peers and by posterity. Furthermore, he believed that life followed art and, consequently, that life was best understood through the prism of art. Whether this is a universal law, as Wilde claimed, it is certainly a law that applies to Wilde himself. There is no way of understanding the true Wilde without first understanding the truth of his art. This was Wildes view and this is also the view that underpins the approach of this study.

Every great man nowadays has his disciples, Wilde wrote, and it is always Judas who writes the biography. These should be cautionary words for any prospective biographer, yet, in Wildes case, they have been all too tragically ignored. Over the years he has been served by a string of biographers who have betrayed him with either a kiss or a curse. Robert Sherard and Frank Harris, both journalists by profession and inclination, wrote with vivid sensationalism but questionable accuracy about their friendship with Wilde. Alfred Douglas spent most of his life trying to explain, or explain away, his relationship with Wilde, so that his views on the subject must be regarded as exercises in self-justification with little effort at objectivity. Later biographies of Wilde have sought to sensationalize his life, sacrificing truth on the altar of scandal if necessary. Perhaps the most obvious example was the illustration in Richard Ellmanns biography, published in 1987, purporting to show Wilde in costume as Salom. This was duly reproduced in many reviews of Ellmanns book as a previously unpublished photograph of Wilde, depicting previously unsuspected transvestism. The exclusive was no doubt greatly beneficial to sales and the photograph was subsequently included in halfa dozen works wholly or partially concerned with Wilde. Such was Ellmanns reputation as a scholar that no one questioned the photographs authenticity. Then, in 1994, an article in the Times Literary Supplement proved beyond doubt that the Salom in the photograph was in fact a Hungarian opera singer, Alice Guszalewicz, photographed in Cologne in 1906.

The worst example of this sensationalist approach was the allegation that Wilde contracted syphilis as an undergraduate at Oxford and that, twenty-five years later, he died of the disease. According to Ellmann, and also to Melissa Knox in a more recent study, the fact that Wilde had syphilis is crucial to any understanding of his life or his work. Yet Wilde almost certainly never had the disease and certainly never died of it (see chapter 5). Thus Ellmanns and Knoxs crucial understanding becomes a crucial misunderstanding at the very heart of their respective studies.

It was a growing uneasiness at the misconceptions of these previous studies that was the principal motivation behind the writing of the present work. In particular, the enshrining of Ellmanns study as the definitive biography was in need of serious reappraisal. As a life of Wilde, it is fairly comprehensive in facts while it remains largely uncomprehending of truth. In this context it must be remembered that the distinction between fact and truth was one that Wilde reiterated often. A collage of facts, carefully constructed, can either present a kaleidoscopic truth or a colossal lie. Ellmanns study may not be a colossal lie, but what emerges from its pages is not a true picture of its subject. Certainly, it cannot be considered either final or definitive in its presentation of the man who was Oscar Wilde.

For a purely factual knowledge of Wilde there is no better source than his letters. These were edited with great objectivity and meticulousness by Rupert Hart-Davis whose footnotes are invaluable. Yet for an understanding of the enigmatically elusive truth it is necessary to read between the lines of his letters and beyond the facts of his everyday life. In this respect, no adequate study exists. The transcendent reality at the heart of the man remains an untold mystery.

Next page

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)