Oscar Wilde was born in Dublin in 1854 and is remembered for a diverse literary output encompassing his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, stories for children, poetry, plays including The Importance of Being Earnest, and a wide-ranging selection of essays and other prose works. Despite being highly celebrated in literary and social circles, he was tried for gross indecency following the loss of his libel case with the Marquis of Queensberry, and was sentenced to two years imprisonment. His health never recovered and he died in penury in Paris in 1900. He is buried there in Pre Lachaise cemetery.

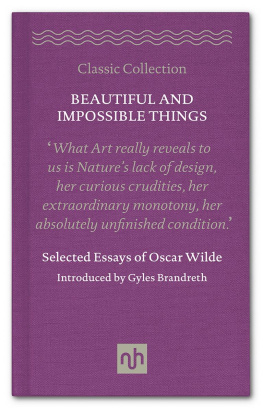

Gyles Brandreth is a writer, broadcaster, actor, former MP and Government Whip, best known as a reporter on The One Show on BBC 1 and a regular on Radio 4s Just a Minute. In the 1970s he produced The Trials of Oscar Wilde on stage and, more recently, played Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest. His many books include political diaries, theatrical biographies, an edition of Oscar Wildes Fairy Tales and a series of detective stories, The Oscar Wilde Mysteries, now published in 22 countries. He is a patron of The Oscar Wilde Society.

over our heads will float the Blue Bird singing of beautiful and impossible things, of things that are lovely and that never happen, of things that are not and that should be.

Oscar Wilde, The Decay of Lying, 1891

Contents

I have more than a hundred books about Oscar Wilde on my study shelves. I could have many more: there are thousands to choose from. Oscar Wilde Studies has become one of the academic industries of our time. But of all the biographies I know, there are two to which I return most often.

One is The Wilde Album, a small book, beautifully written by Merlin Holland, Wildes only grandchild, the son of his second son, Vyvyan Holland, and illustrated with fascinating material drawn from the family archive. Within the book are two pages from an American Confession Album, filled out by Wilde some time in 1877, the year in which he turned twenty-three. Some of the answers Wilde gives are the ones we would expect. Almond blossom is young Oscars favourite fragrance, the lily is his flower of choice. His preferred season is the beginning of autumn and for his Object in Nature he chooses The sea (when there are no bathing machines).

Some of the answers provoke a smile: What is your favourite occupation? Reading my own sonnets.

If not yourself, who would you rather be? A Cardinal of the Catholic Church.

And several make us ponder: What are the sweetest words in the world? Well done!

What are the saddest words? Failure!

What is your aim in life? Success: fame or even notoriety.

The other biography I consult on a regular basis is, predictably, Richard Ellmanns magisterial Oscar Wilde, first published in 1987. Ellmann concludes his book with an assessment of his heros place in the modern world. He quotes Wilde on a fellow Victorian of note and notoriety, the Irish nationalist leader, Charles Stewart Parnell: There is something vulgar in all success The greatest men fail, or seem to have failed. Ellmann goes on:

what was true of Parnell is in another way true of Wilde. His work survived as he had claimed it would. We inherit his struggle to achieve supreme fictions in art, to associate art with social change, to bring together individual and social impulse, to save what is eccentric and singular from being sanitised and standardised, to replace a morality of severity by one of sympathy. He belongs more to our world than to Victorias. Now beyond the reach of scandal, his best writings validated by time, he comes before us still, a towering figure, laughing and weeping, with parables and paradoxes, so generous, so amusing, so right.

That is wonderfully put, though I might quibble with that final so right. Wilde is occasionally so wrong. And he is sometimes quite absurd. As he admitted in a letter to Arthur Conan Doyle, Between me and life there is a mist of words always. I throw probability out of the window for the sake of a phrase, and the chance of an epigram makes me desert truth. Still I do aim at making a work of art And, right or wrong, rational or absurd, Oscar Wilde is always fascinating. He is the man you hope will walk into the room and come to sit at the spare place at your table.

The creator of Sherlock Holmes met Wilde first, over dinner, in 1889 and was immediately charmed: His conversation left an indelible impression on my mind. He towered above us all, and yet had the art of seeming interested in all that we could say. He had delicacy of feeling and tact He took as well as gave, but what he gave was unique.

George Bernard Shaw, Wildes near-contemporary and fellow Irish playwright, said of him: He was incomparably the greatest talker of his time perhaps of all time. Laurence Housman, English playwright and poet, brother of A.E., described Wildes unique speaking style: The smooth, flowing utterance, sedate and self-possessed, oracular in tone, whimsical in substance, carried on without halt, or hesitation, or change of word, with the queer zest of a man perfect at the game.

There are no known recordings of Oscar Wilde speaking, but you can hear his voice very clearly in the pages that follow. These essays illustrate his remarkable way with words and reveal both a range of his opinions on things that mattered to him and a flavour of his philosophy of art and life.

If you are looking for the company of Oscar Wilde on song you are in for a treat. If you are hoping to find a Wildean world-view that holds together at all times, you will be disappointed. As he says in Aristotle at Afternoon Tea (and elsewhere: if he borrowed liberally from other writers, he borrowed most liberally from himself): Consistency is the last refuge of the unimaginative.

Wilde is ashamed neither of intelligent plagiarism nor of self-contradiction. As he put it in one of the effusive letters he wrote to the twenty-year-old undergraduate, Harry Marillier, in 1885: I myself would sacrifice anything for a new experience, and I know there is no such thing as a new experience at all. I think I would more readily die for what I do not believe in than for what I hold to be true. I would go to the stake for a sensation and be a sceptic to the last! Only one thing remains infinitely fascinating to me, the mystery of moods.

What is truth? Wilde liked to ask. It is he would answer, smiling, ones last mood.

The material in this collection reflects his last mood at the time of writing. It also reflects the variety of his interests and enthusiasms, the breadth of his reading (Oscars Books: A Journey Around the Library of Oscar Wilde, Thomas Wright, 2009, is another of my favourites), the quality of his questing and quixotic mind, as well, of course, as his particular, not to say peculiar, upbringing.

Oscar Fingal OFlahertie Wills Wilde did not spring into the world fully formed. Born in Dublin on 16 October 1854, he was the remarkable son of remarkable parents. His mother, Jane Elgee (182196), was a formidable figure: six foot tall, Junoesque in build, assertive in temperament. She came from an achieving family: her cousin discovered the North-West Passage, her brother became one of Americas most noted jurists. A gifted linguist (she translated novels from French and German) and a prolific poet, under the pen-name of Speranza, she was celebrated for her nationalist writings and zeal.

Oscars father, William Wilde (181576), if some inches shorter than his wife, was no less remarkable and no less committed to Irelands heritage and integrity. He, too, was a prolific author (in 1851, the year of their marriage, he published

Next page

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)