Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

THE CRITICAL WRITINGS of OSCAR WILDE

AN ANNOTATED SELECTION

EDITEDNICHOLAS FRANKEL

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

2022

Copyright 2022 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Jacket design: Gabriele Wilson

Jacket illustration: Yuko Shimizo

978-0-674-27182-1 (cloth)

978-0-674-28742-6 (EPUB)

978-0-674-28741-9 (PDF)

Publication of this book has been supported through the generous provisions of the Maurice and Lula Bradley Smith Memorial Fund.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Wilde, Oscar, 18541900, author. | Frankel, Nicholas, 1962 editor.

Title: The critical writings of Oscar Wilde : an annotated selection / Oscar Wilde ; edited by Nicholas Frankel.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022010857

Subjects: LCSH: Criticism. | LiteratureHistory and criticism. | EnglandSocial life and customs19th century.

Classification: LCC PR5811 .C75 2022 | DDC 824/.8dc23/eng/20220425

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022010857

CONTENTS

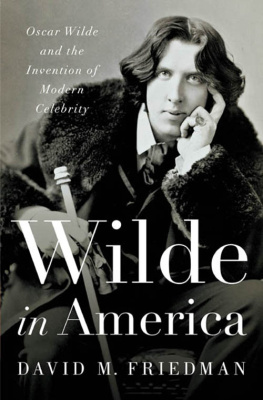

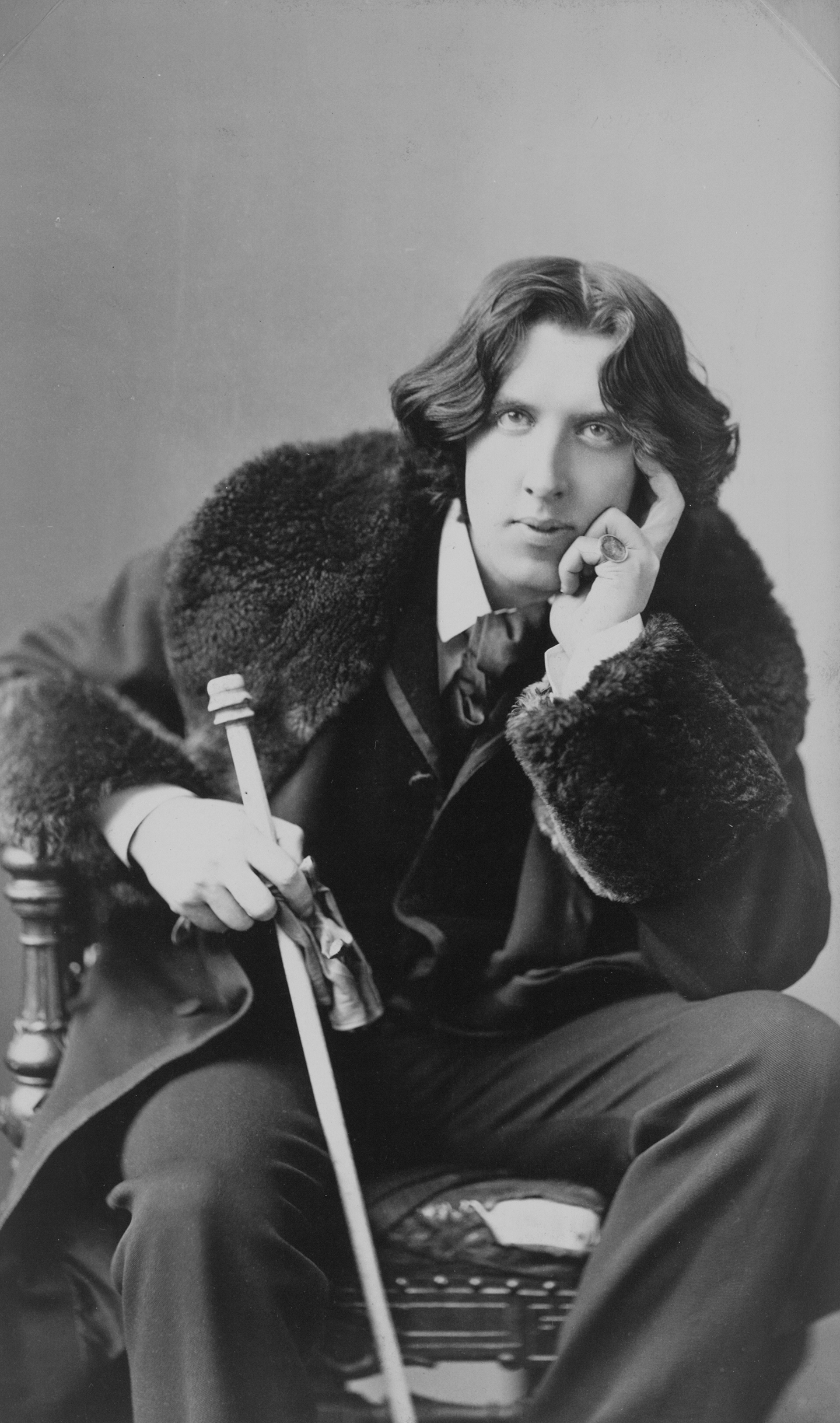

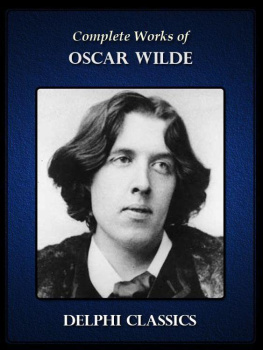

Photoportrait of Wilde, by Napoleon Sarony, 1882.

Not by wrath does one kill but by laughterNietzsche

Although chiefly known today as the paragon of wit and style, a pathbreaking sexual dissident, and the Victorian eras greatest playwright, Oscar Wilde was also Victorian Britains most provocative, entertaining, and forward-thinking critic. For a period of roughly seven years leading up to his career as a successful playwright in the early 1890s, he published literary and cultural criticism in an array of periodicals, including articles in the leading monthlies The Nineteenth Century and The Fortnightly Review and over eighty book reviews in Londons Pall Mall Gazette alone. His only published book of criticism, the aptly named Intentions, is regarded by many as among the finest of his writingsthe poet W. B. Yeats called it a wonderful book and the American essayist Agnes Repplier judged it the best book published in 1891, while the New York Times described it as Wildes finest prose workand three years after its publication Wilde himself remarked, I simply love that book!

As with everything he did, Wilde approached the writing of criticism with wit, irony, and a consummate sense of style, so much so that his critical writing is often hardly recognizable as criticism. Like Platos Symposiumcalled by Wilde of all the Platonic dialogues perhaps the most perfectWildes major critical expositions, The Decay of Lying and The Critic as Artist, are written in the form of conversations or dialogues, the first of them between characters who are named for Wildes children, Vivian and Cyril, who were two and three years old, respectively, at the time of publication; and they eloquently demonstrate Wildes notions that recreation, not instruction, is the aim of conversation and that conversation is seriously undermined by a permanent gravity of demeanour and a general dulness of mind. Even Wildes most sophisticated and trenchant criticism is inflected by the rhythms and intonations of his speaking voicethe only essential for a good conversationalist, Wilde once remarked, is the possession of a musical voiceand, as Wilde observed of another erudite and witty talker, reading his critical writings is like entertaining Aristotle at afternoon tea.

Together with its conversational character, perhaps the most striking and surprising feature of Wildes criticism is its wit. The epigrams with which some of his earliest published pieces beginMr. Whistler made his first public appearance as a lecturer on art, and spoke with really marvellous eloquence on the absolute uselessness of all lectures of the kind; A man can live for three days without bread, but no man can live for one day without poetry; Who, in these degenerate days, would hesitate between an ode and an omelette, a sonnet and a salmis?set the tone in this regard. Reviewing Intentions in The Academy, Richard Le Gallienne observed that there will be many who take him seriously; but let me assure them that Mr. Wilde is not of the number, and Wilde himself remarked that, while art is the only serious thing in the world, the artist is never serious. Wilde would certainly have wanted his criticism to be understood with a smile and as an extension or expression of his artCriticism is itself an art, he declares in The Critic as Artist, for like the artist, the critic works with materials, and puts them into a form that is at once new and delightfuland it is much to the point that many of the epigrams sprinkled throughout Wildes criticism anticipate those to be found in his fiction and his plays. Given this epigrammaticism, it is not surprising that Wildes career as a critic culminated in Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young and A Few Maxims for the Instruction of the Over-Educated, just months before his criminal conviction. In these astonishing displays of epigrammatic wit and wisdom, Wilde elevated the epigram into a distinctive literary form in its own right.

If he was right to highlight Wildes absence of seriousness, however, Le Gallienne was surely wrong to write that Mr. Wilde [is] essentially a humorist who has taken art-criticism for his medium and his intricate tracery of thought and elaborate jewel-work of expression is simply built-up to make a casket for one or two clever homeless paradoxes. The verbal cut-and-thrust of Wildes social comediesin which the young waste no time in contradicting their eldersis the keynote of Wildes critical writings, too, even those among them not explicitly written in the form of the dialogue. Perhaps the most straightforward and seemingly earnest of his essays, The Truth of Masks, for instance, ends tongue-in-cheek with the essayist declaring, not that I agree with everything I have said in this essay. There is much with which I entirely disagree. The essay simply represents an artistic standpoint, and in aesthetic criticism attitude is everything. Conversation implies differences in opinion, Wilde insists elsewhere, and while the well-bred contradict other people, only the wise contradict themselves. Diversity of opinion, Wilde insists in the Preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, shows that the work is new, complex, and vital.

If Wildes criticism begs to be contradicted, it is also willfully ironic, subordinating what is said to what remains unsaid or merely implied. (Only the great masters of style ever succeed in being obscure, Wilde declares in Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young.) Wildes backhanded compliment about Whistlers really marvellous eloquence on the absolute uselessness of all lectures is typical in this regard, not merely because it subtly sets the stage for the serious intellectual disagreements that Wilde goes on to express in the course of his review of Whistlers important Ten OClock lecture, but also because it punctures Whistlers vaingloriousness and hubris in venturing into a field, the public lecture on art, that Wilde had in recent years made more or less his own. (In this regard, Wildes review of Whistlers lecture anticipates his short story The Remarkable Rocket, published three years later, in which Wilde parodies Whistler allegorically as a remarkable firework that, after failing to go off properly, gets thrown into a ditch, where it eventually explodes unseen.) Similarly, the joy with which Wilde delights in classifying the various kinds of artists models, in London Models, gives a clue that the essay, like Wildes Philosophy of Dress, extends far beyond its ostensible subject to embrace the liberation of the body and of gender from the rigid constraints imposed upon them by Wildes fellow Victorians. The essays wit is decidedly risqu. When Wilde remarks that artists models usually marry well, and sometimes they marry the artist, that while such models are philistines intellectually, physically they are perfectat least some are, and that though they cannot appreciate the artist as artist, they are quite ready to appreciate the artist as a man, the unspoken eroticism and sly sexual provocativeness of the essay rise briefly to the surface, underscoring Wildes aphorism in the Preface to

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)