Much is owed to many. Ill start with Tom Mayer, an editor of uncommon ability whose insightful comments and unwavering commitment to this project made our collaboration a pleasureand the book much better. Great thanks, also, to my agent David Black, who has always been a source of good advice and support.

Several friends read parts of the manuscript along the way. Ben Yagodathe smartest person I knowprovided invaluable help and was always available to give it. Every writer should have such a generous friend. Others who were equally lavish with their comments and/or encouragement were Erica Berger, John Capouya, Paul Gardner, Neal Hirschfeld, Simon Joseph, Stanley Mieses, Lawrie Mifflin, Joel Rose, Lee Schreiber, and Michael Sorkin. The scholar Joseph Bristow, a professor of English at UCLA, who has written widely and well on Wilde, was a great help to me, as was Donald Mead, editor of The Wildean, and John Cooper, the host/writer of the wonderful Oscar Wilde in America website, and the leader of an enchanting walking tour of Oscar Wildes New York. Two geologists, Vince Matthews of the National Mining Hall of Fame, in Leadville, Colorado, and Fred Mark (another Coloradan), taught me everything I know about nineteenth-century silver mining.

Librarians in several institutions were extraordinarily helpful to (and patient with) me. I owe special thanks to the staff at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, in Los Angeles, the home of an outstanding collection of Wildeana, and where every question I asked was answered with professionalism. Similar gratitude is owed to the staffs of the British Library in London, New York Universitys Bobst Library, and the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature at the New York Public Library, as well as the NYPLs Humanities and Social Science Library. This project also benefited from the excellent work of the photo researcher Donna Cohen, the copy editor Janet Biehl, and the production editor Ryan Harrington.

But, most of all, Im grateful to my wife Marion Ettlinger, without whom this book never would have happened.

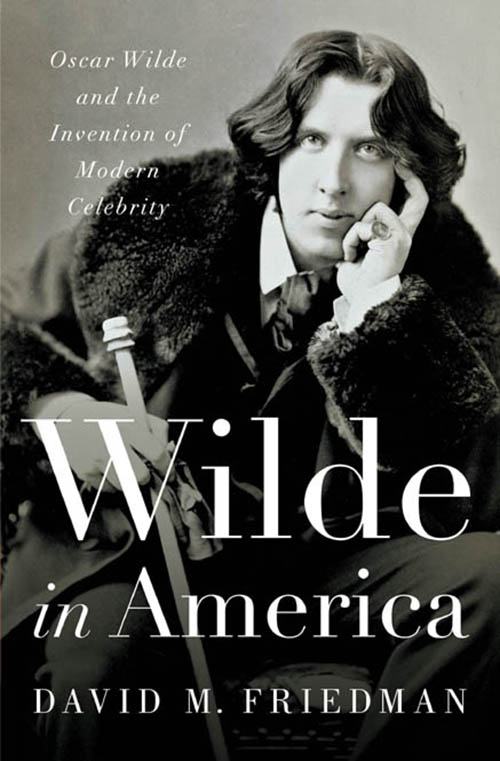

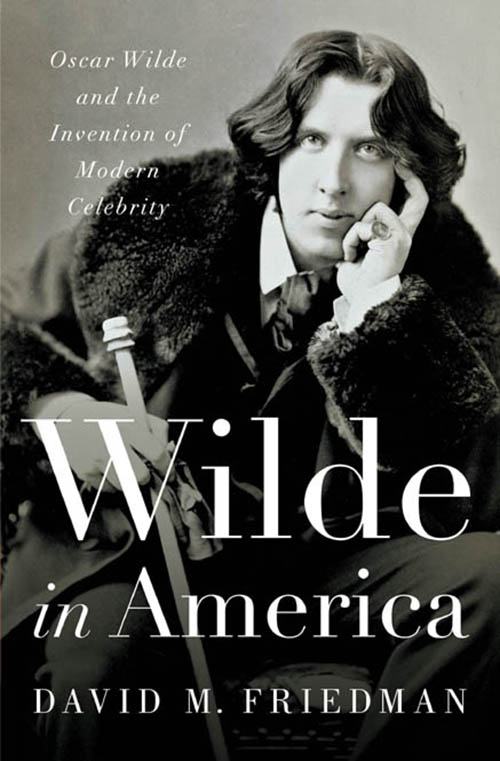

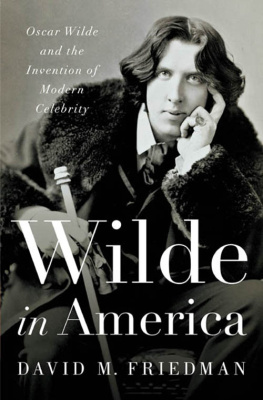

ALSO BY DAVID M. FRIEDMAN

A Mind of Its Own: A Cultural History of the Penis

The Immortalists: Charles Lindbergh, Dr. Alexis Carrel, and Their Daring Quest to Live Forever

S hortly after eleven p.m., on February 20, 1892, nine years after he returned to England, Oscar Wilde heard the words he had longedand plannedto hear all his life. AUTHOR! AUTHOR! chanted the audience at St. Jamess Theatre, where the curtain had just fallen on the first of his comedies to be staged in London: Lady Windermeres Fan, his effervescent satire of morality and marriage. He would not disappoint them. Wearing a gray wool jacket with a black velvet collar, beige trousers, a white waistcoat edged in moir ribbon, and a dyed green carnation in his buttonhole, Wilde emerged from the wings and bowed to his admirers. In his gloved left hand he held a gold-tipped cigarette, which he smoked with pleasure as the cheering continued, until he held up that hand and said: Ladies and Gentlemen, I have enjoyed this evening immensely. The actors have given a charming rendering of a delightful play, and your appreciation has been most intelligent. I congratulate you on the great success of your performance, which persuades me that you think almost as highly of the play as I do myself. In one glorious night Wilde had achieved both goals he had set for himself at Oxford: he was famous as the writer of an adored new play; and he was notorious as the man who had delivered that cheeky speech.

Both demanded celebration. So after sending his beaming wife Constance home to their exquisitely decorated house in ChelseaWilde had married in 1884 and was now the father of two sonshe went for a late supper at Williss, a spot favored by Londons theater crowd. His dining companions, all of them young males, included the aspiring art critic Robbie Ross (who had lived for a time at the Wildes home), Reggie Turner (a recent Oxford graduate who would become the gossip columnist for the Telegraph), Edward Shelley (a good-looking publishing clerk who, according to Neil McKenna, author of The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde, the playwright would take to bed that night at the Albemarle Hotel), and an even better-looking student from Magdalen College Wilde was just getting to know, the Marquess of Queensberrys third sonLord Alfred Douglas, known to his friends as Bosie.

Wilde would have even more reasons to celebrate in the near future. Fan appeared before packed houses for six months at St. Jamess, then toured the provinces with equal success, after which it returned to London for another profitable runespecially for Wilde. He had rejected the actor-producer George Alexanders offer of 1,000 for all rights to his play, instead taking a percentage of the box-office receipts. (Alexander played Lord Windermere in the original cast of Fan.) By years end Wilde had earned 7,000the equivalent of 700,000 todayspending a good chunk of it on lavish meals and vintage champagne at Londons best restaurants, almost always joined by a coterie of male acolytes, in lively soirees that often made the newspapers. Wilde wasnt just the conversational star of those dinners, he was the talk of all London and, even more delightful from his point of view, he was often asked to speak about his playwhich he took to mean himselfin public. When a left-leaning politician at one event praised him for calling a spade a spade in Fan, by lashing out against the hypocritical social mores of the ruling class, Wilde brought down the house by protesting that he had never called a spade a spade. The playwright who does so, he said, should be condemned to use one.

His second hit, A Woman of No Importance, a biting take on the different rules of behavior set by society for men and women, especially in the realm of sex, opened on April 19, 1893, at the Theatre Royal, where it ran for 118 nights. When the Prince of Wales told him of his admiration for the play, Wilde confessed he worried his final act was too long. Do not alter a single line, said the prince. Sir, your wish is my command, said Wilde. After spending the next year showing off at parties for which the hostesses invitations often included the message, To Meet Mr. Oscar Wilde, he opened his next play, An Ideal Husband, on January 3, at the Haymarket Theatre. A hilariously astute look at the connections (and disconnects) between public and private behavior, Husband would run for 124 nights, earning Wilde even more fame and money, and this praise from the often cranky George Bernard Shaw: Mr. Wilde is to me our only thorough playwright. He plays with everything: with wit, with philosophy, with drama, with actors and audiences, with the whole theatre. While Husband was still drawing crowds to the Haymarket, Wilde opened another play a few blocks away, his trivial comedy for serious people, The Importance of Being Earnest. Just before it premiered on February 14, 1895, at St. Jamess, he was asked if he thought his new playacclaimed today as his masterpiecewould be a success. The play is a success, he said. The only question is whether the first nights audience will be one. It was. Decades later Allan Aynsworth, who played Algernon Moncrief that night, said: In my fifty-three years of acting, I cannot remember a greater triumph than the first night of The Importance of Being Earnest

Next page

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)