Nihil Obstat. Rev. Lawrence Landin, O.F.M

Rev. Edward Gratsch

Imprimi Potest: Rev. Jeremy Harrington, O F.M.

Provincial

Imprimatur: +James H. Garland, V.G.

Archdiocese of Cincinnati

June 15, 1989

The nihil obstat and imprimatur are a declaration that a book is considered to be free from doctrinal or moral error. It is not implied that those who have granted the nihil obstat and imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed.

The excerpt from Children of Sanchez Autobiography of A Mexican Family , 1961 by Oscar Lewis, is reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc.

The excerpt from Catholicism , by Richard P McBrien, 1981 by Richard McBrien, is reprinted by permission of Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.

Scripture citations are the authors paraphrase.

Cover and book design by Julie Lonneman

ISBN 0-86716-101-9

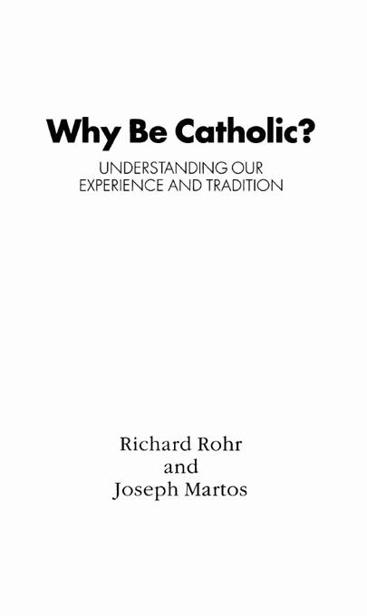

1989, Richard Rohr and Joseph Martos

All rights reserved.

Published by St Anthony Messenger Press

Printed in the U.S.A.

Preface

In 1985 Franciscan Father Richard Rohr presented four talks at St. Francis Renewal Center in Cincinnati, Ohio. He spoke on a topic of increasing concern to many people during the closing decades of the 20th century: the meaning of their identification with the Christian tradition and the purpose of their membership in the Roman Catholic Church.

Following the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, Catholics began to wonder about their uniqueness within the broader Christian tradition and to question the value of working within the institutional structures of Catholicism. Conservative Catholics asked whether the Church was giving up too much too fast, and liberal Catholics asked why the Church was not changing faster.

In the 1970s the spirit of ecumenism softened the sharp divisions between Protestantism and Catholicism. Ecumenical dialogue with the separated brethren reduced the tension that had existed between the churches since the Protestant Reformation, and it overcame the bitterness of four centuries of religious rivalry. But ecumenism also led well-meaning Christians on both sides of the dialogue to ask whether the Catholic Church was really as unique as it once appeared. Could it be that Catholicism was just one valid way to be Christian, without any real claim to superiority or privilege?

The spirit of reform in the first years after the Council eliminated much that had been uniquely Catholic in the Churchs public life: the unchanging Latin Mass and sacraments, statues of saints and devotions to the Blessed Mother, clerical clothing and religious dress, rigid adherence to Church laws and unswerving obedience to the pope, to name a few. During the 1980s the pace of practical reform slowed down, however, and those who viewed many traditional Catholic practices as antiquated saw their hopes of Church renewal fading. Could it be, they asked, that Catholicism is institutionally incapable of honest and thorough ongoing reform?

On both the right and the left, therefore, Catholics have been wondering about the Church and their role in it. Richard Rohr, as pastor of New Jerusalem Community in Cincinnati, felt that tension both within his community and within the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. I, as theologian and teacher at Xavier University, experienced it both within the academic world and within the pastoral world of parish life. No place or group is immune from the soul-searching going on within the Church about the Church.

At the extremes of both right and left, some people have felt so strongly that the Catholic Church is not what it ought to be that they have severed their ties with it. Some have chosen to start churches of their own, claiming they are thus preserving true Catholicism. Some have chosen to join other churches, claiming Roman Catholicism has lost touch with true Christianity.

Richard Rohr and I believe that the truth is to be found in that broad middle ground where tension is experienced the most. The truth is to be lived not by giving in to the temptation to escape to the extremes but by accepting the Catholic heritage while working to change the institutional Church from within. By being truthful to the broad tradition of the past, we can hope to influence its course in the future.

Those who listened to Richards talks in 1985 came to understand how challenging it is to be truly Catholic. When I listened to the tapes of those talks, I felt that Richards understanding deserved to reach a wider audience. With his permission and the encouragement of St. Anthony Messenger Press, I took on the task of editing those tapes and writing a book that expresses the understanding we both have about the tradition we call our own.

I hope that those who read this book will appreciate more fully the challenge of being deeply rooted in the past while moving with the Catholic Church into the 21st century.

Joseph Martos

Allentown College

Contents

Why be Catholic?

That is a question Catholics never asked a generation ago. People who were thinking about joining the Catholic Church may have asked it, but not Catholics themselves. If you were born Catholic, you simply accepted the faith, its traditions and beliefs.

The Church gave those of us who were born and raised Catholics a strong sense of identity. Catholicism told us who and what we were as human beings, as Christians, even as individuals. We were nurtured and sustained by that great maternal institution known respectfully as Holy Mother Church.

Catholicism was a total worldview, a total system of thinking, feeling and behaving. You could just as easily stop being Catholic as you could stop being blackwhich is to say you really could not. You might formally leave the institution, but you could not change the way you had been taught to look at the world, God, religion or yourself.

Today the Catholic Church is much different from a generation ago. Pope John XXIIIs program of aggiornamento or updating succeeded far better than anyone imagined. American Catholicism, in particular, is very different from what it was prior to the 1960s. The Second Vatican Council ushered in an era of ecumenism which broke down many barriers between the Catholic Church and other Christian denominations.

The greater openness of the Church is good, and the greater acceptance of others is good. But a Church without walls also has a harder time defining itself. Today it is not so easy to say what makes Roman Catholicism different from other forms of Christianity.

Young Catholics todaythose who have grown up considering the changes of Vatican II normaldo not have nearly the sense of religious identity that their parents did. They do not see much real difference between their church and the churches that their friends belong to. At some point in their life, usually in early adulthood, they have to face seriously the question, Why be Catholic?

Older Catholics today, too, sometimes find themselves wondering about the Church. For any number of reasons, they can feel themselves being tempted to leave and join some other church. In their case the question is more like, Why remain Catholic?

No matter which way the question is put, it requires an answer.

The answer to that question, however, cannot be simple. The Catholic Church is not a small institution. The Catholic faith is not an easily recited set of beliefs. The Catholic heritage is not a brief tradition.

Next page