Landmarks

Page-list

SOLZHENITSYN AND AMERICAN CULTURE

THE CENTER FOR ETHICS AND CULTURE SOLZHENITSYN SERIES

Under the sponsorship of the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame, this series showcases the contributions and continuing inspiration of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (19182008), the Nobel Prizewinning novelist and historian. The series makes available works of Solzhenitsyn, including previously untranslated works, and aims to provide the leading platform for exploring the many facets of his enduring legacy. In his novels, essays, memoirs, and speeches, Solzhenitsyn revealed the devastating core of totalitarianism and warned against political, economic, and cultural dangers to the human spirit. In addition to publishing his work, this new series features thoughtful writers and commentators who draw inspiration from Solzhenitsyns abiding care for Christianity and the West, and for the best of the Russian tradition. Through contributions in politics, literature, philosophy, and the arts, these writers follow Solzhenitsyns trail in a world filled with new pitfalls and new possibilities for human freedom and human dignity.

SOLZHENITSYN AND

AMERICAN CULTURE

THE RUSSIAN SOUL IN THE WEST

Edited by

David P. Deavel and Jessica Hooten Wilson

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2020 by University of Notre Dame

Published in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020940884

ISBN: 978-0-268-10825-0 (Hardback)

ISBN: 978-0-268-10828-1 (WebPDF)

ISBN: 978-0-268-10827-4 (Epub)

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at

Dedicated to the Memory of Edward E. Ericson Jr.,

Christian, scholar, mentor

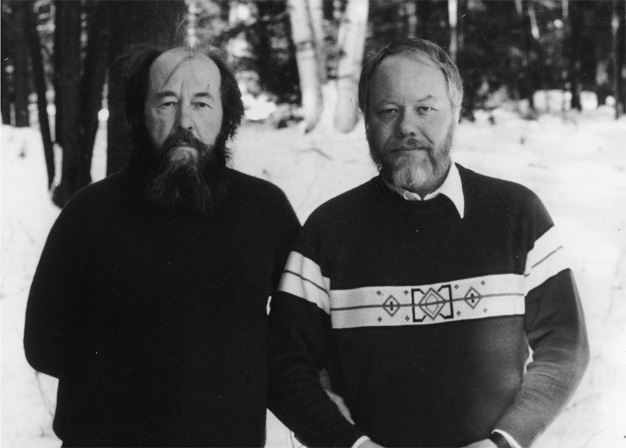

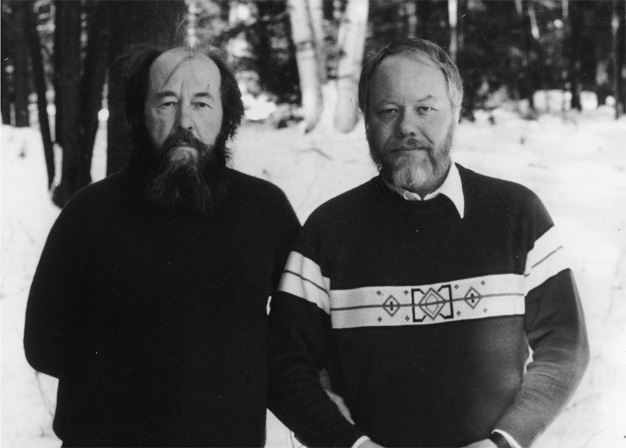

Edward E. Ericson Jr. (right) with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn at the Russian authors

Vermont home, 1983. Photo courtesy of the Ericson family.

And there was Professor Edward Ericson of Calvin College, Michigan, with whom Id become acquainted through an exchange of letters after his book Solzhenitsyn:

The Moral Vision was published. He had been suggesting for a good while that a single-volume version of Archipelago should be produced for Americawhere almost no one was capable of reading three volumesand that I myself should do this, or entrust someone else with it. If I liked the idea, he said, it could be Ericson himself, and he would willingly take it on. I had taken a look at his proposal andwhy not? it could certainly serve a purpose. Without the deeper probings into Russian matters, and with the loss of historical details and some of the atmosphere, it could work well for the incurious or cluttered brains of American youth. And the assiduous Ericson set to work. Then I had to look through all the places hed bracketed and correct his choices here and there....

At the end of 1983 Ericson came to discuss the progress of his work. I corrected some choices, but to a large extent hed chosen well, knowing as he did the mentality of young Americans. He turned out to be well built, big, sturdy, his face framed by a close-cut beardwith something of the ships skipper about him. Measured, very good-heartedand concerned above all with spiritual matters. He worked absolutely selflessly and, to ease the procedure of negotiating with publishers, he renounced any fee.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Between Two Millstones, Book 2:

Exile in America, 19781994, chap. 10, Drawing Inward.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

JOHN WILSON

The critic George Steiner, who died in February 2020 at the age of ninety, began his extraordinary career with a book called Tolstoy or Dostoevsky: An Essay in Contrast, published in 1960. The following year, Steiner contributed the foreword to a Signet Classics edition of stories by Alexander Pushkin, The Queen of Spades, and Other Tales, in which he argued that anyone who comes to Pushkin, notably to his stories and short novels, from an American background will have certain distinct advantages. He will experience a shock of familiarity. Steiner goes on to suggest deep similarities between Russia and America, geographical, cultural, and historical (both these two great land masses, he observes, stood in a crucial, problematic relation to Europe), and draws parallels between Russian and American literature. Whether or not the reader is entirely persuaded by Steiners argument, I think it would be worth the trouble to track down this foreword as an appetizer to the feast that is prepared for us in Solzhenitsyn and American Culture.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is sometimes described (especially today) as if he were a monomaniac, always speaking in one register, hectoring, denouncing, laying down the law. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, he was, among other things, a connoisseur of irony and a master ironist. The same was true of Ed Ericson, my former teacher and dear friend whose scholarship on and advocacy for Solzhenitsyn inspired the book you hold in your hands. Both men would relish the ironies that attend its publication. Talk about Russian culture in 2019? Isnt that absurdly antiquarian? No. Its precisely such narrow views that this volume is intended to counter.

In a column for First Things posted on January 25, 2019, occasioned by the publication of Solzhenitsyns Between Two Millstones, Book 1: Sketches of Exile, 19741978, I acknowledged that Solzhenitsyn was a genuinely great man and an inspiration to millions, but also all too human-as we all are. We should be able to talk about such a figure without lurching between hagiography and drive-by character assassination. In that column, I registered my disappointment at the range of pieces marking Solzhenitsyns centenary in December 2018:

In fact, what we got was pretty thin gruel. Some pieces did appear, of course, and more may come, but there was no sense of a lively conversation equal to the richness of the subject. Many of the pieces that were published brought to mind Solzhenitsyns own over-the-top invective against the spiritual and intellectual decadence of the West. (How did that line about sewage go?) He was a fascist, you see, or a man with fascistic leanings, a harbinger of the dark turn in Europe and in the United States toward the far right. Even among the more nuanced pieces, there was rarely any reflection on Solzhenitsyn as a writer.

Happily, the widely ranging essays gathered in Solzhenitsyn and American Culture more than make up for this deficiency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are dedicating this book to Edward E. Ericson Jr., and we want to acknowledge that his scholarship has made many of these contributions possible. Several of the contributors to this volume were friends with Ericson and acknowledge their debt to his work on Solzhenitsyn. Through my friendship with Ed, I (Jessica Hooten Wilson) had the opportunity to visit Moscow; to meet the inimitable Natalia Dmitrievna Solzhenitsyn and her sons Yermolai, Ignat, and Stepan, who have done so much to further their fathers legacy; and to become friends with several Solzhenitsyn scholars, who have contributed to this volume. Thank you also to John Brown University for my (Jessica Hooten Wilson) 201718 sabbatical and Summer Scholars Grant, which gave me the time and resources to complete this manuscript. For editing help early on in the process, thank you to Jamie Carlson, and to Maura Kennedy for tracking down information and Nancy Sannerud for technical assistance. Great thanks and our continual gratitude to Stephen Little and Steve Wrinn at the University of Notre Dame Press and to the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame for their dedication to Solzhenitsyns legacy. Finally, deep gratitude to the Solzhenitsyn family (especially Ignat) for their help in providing the volumes epigraph.