Published in 2016 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2016 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

First Edition

Editor: Karolena Bielecki

Book Design: Kris Everson

Reviewed by: Robert J. Conley, Former Sequoyah Distinguished Professor at Western

Carolina University and Director of Native American Studies at Morningside College and Montana State University

Supplemental material reviewed by: Donald A. Grinde, Jr., Professor of Transnational/American Studies at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Photo Credits: Cover Marilyn Angel Wynn/Native Stock/Getty Images; pp..

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Royce, Topher.

Nez Perce / Topher Royce.

pages cm. (Spotlight on Native Americans)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4994-1695-4 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-4994-1696-1 (6 pack)

ISBN 978-1-4994-1698-5 (library binding)

1. Nez Perc IndiansHistoryJuvenile literature. 2. Nez Perc IndiansSocial life and customsJuvenile literature. I. Title.

E99.N5R69 2016

979.5004974124dc23

2015009050

Manufactured in the United States of America

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #WS15PK: For Further Information contact Rosen Publishing, New York, New York at 1-800-237-9932

CONTENTS

ORIGIN OF THE NEZ PERCE

CHAPTER 1

The Nez Perces are a people of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon in the western United States. Today they number about 3,000.

No one knows exactly how the Nez Perce and other Indian tribes got to North America. Like many Native groups, however, the Nez Perces explain their beginnings in an origin story.

According to this story, before there were people in the world, the animals, including Coyote, could talk and act like humans. One day a huge monster called Iltswewitsix began eating everything in sight. Coyote tied himself to the earth, hoping Iltswewitsix wouldnt eat him up with everything else, but the monster found him. Coyote quickly jumped down Iltswewitsixs throat. He went to the monsters heart, took out his stone knife, and began to cut its body up into pieces. Then he threw the pieces all over the land, creating many different tribes.

When he was done, Coyote realized that no tribe was in the Kamiah Valley in Idaho. Coyote shook some drops of the monsters blood off his fingers and made the last and best tribe, the Nimiipuu, or Real People, as the Nez Perces call themselves, right where he stood.

The Payette River flows through Nez Perce homelands in Idaho.

CONTACT WITH EUROPEAN AMERICANS

CHAPTER 2

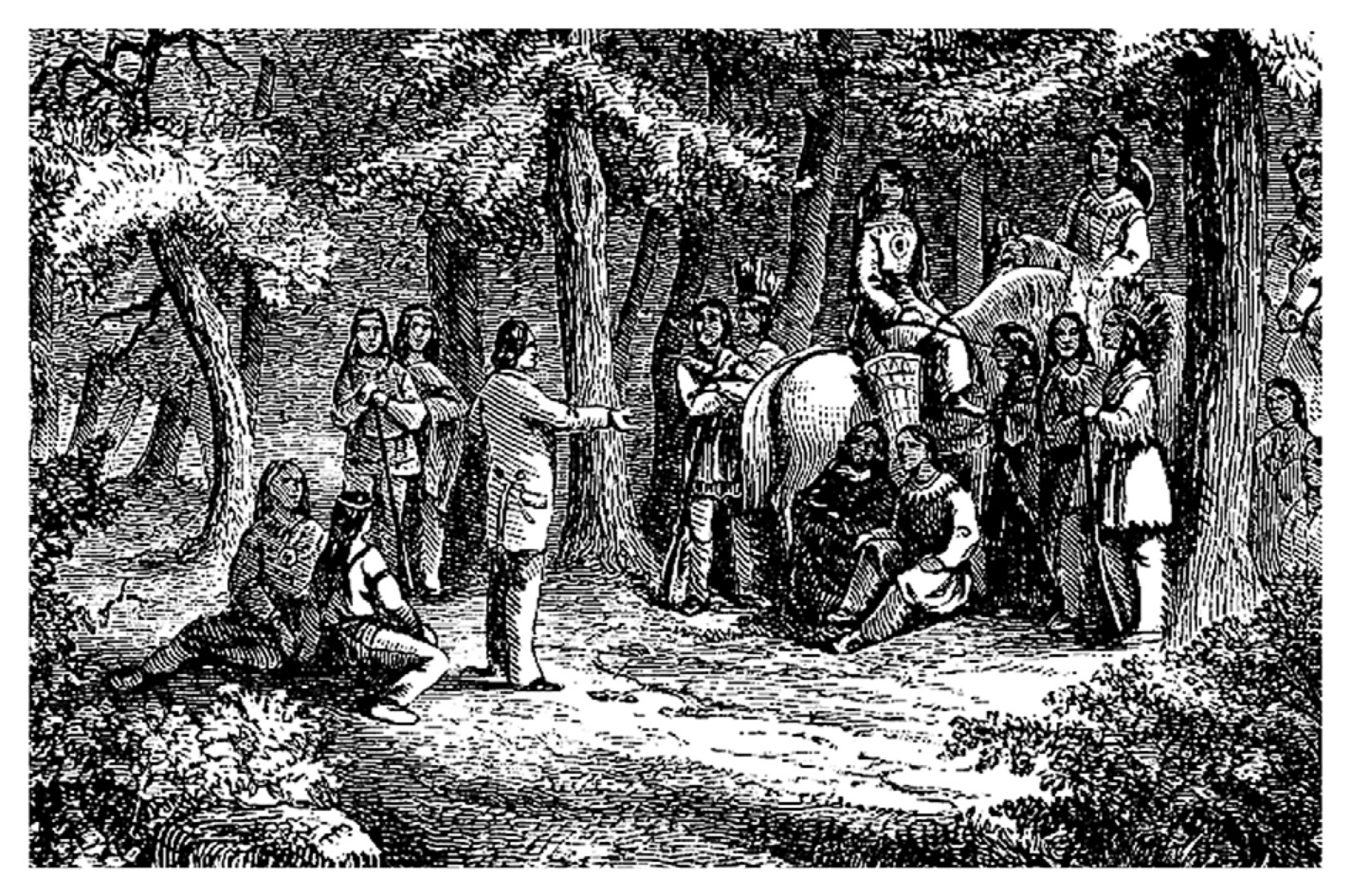

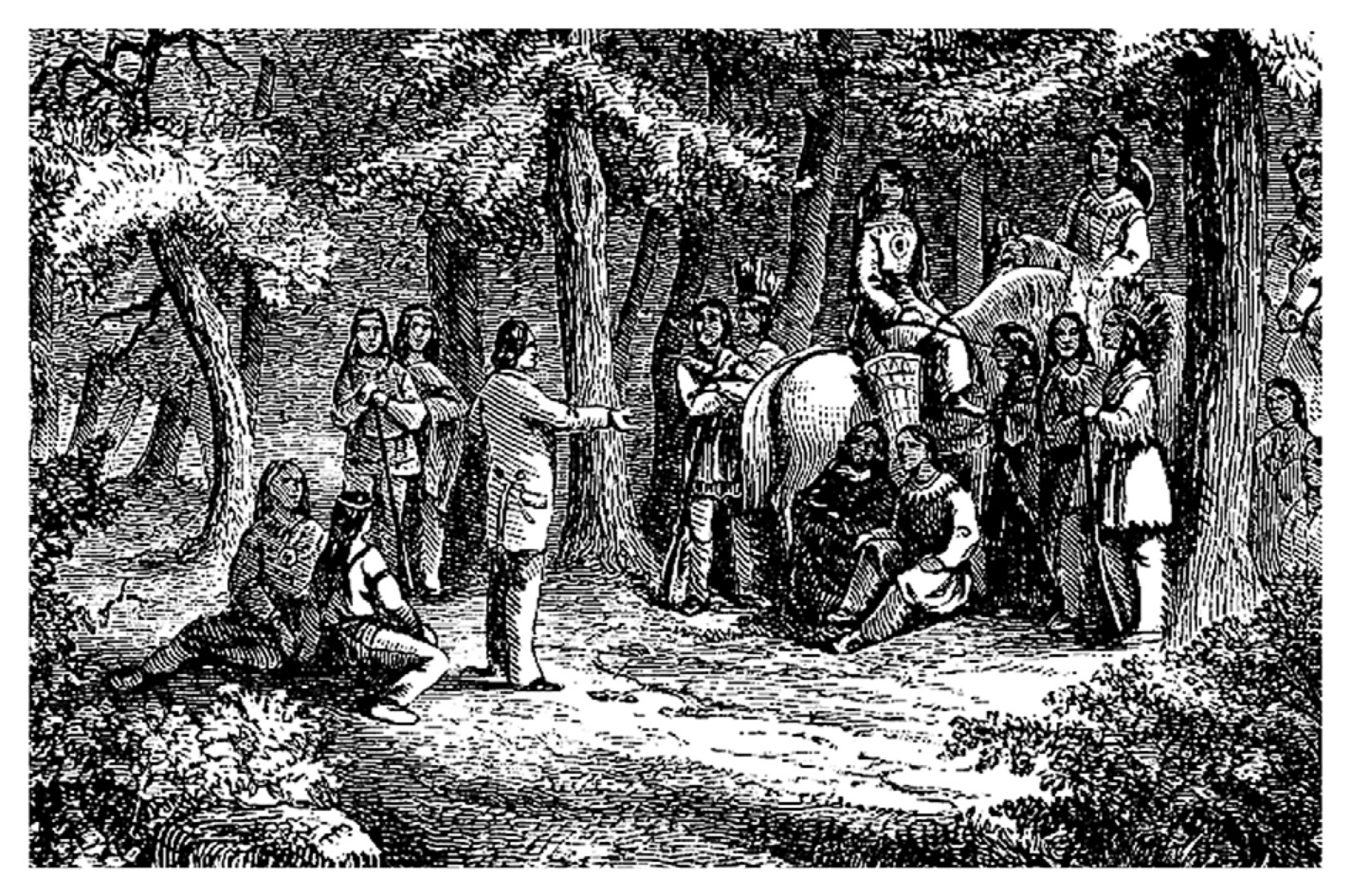

Sent by President Thomas Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark led an to map and explore a large part of North America. They met some of the Nez Perce people in 1805. The Nez Perces fed Lewis and Clarks weak and hungry group, helped them make canoes, and guided them toward the Pacific Ocean. In return, Lewis and Clark gave the Nez Perces gifts of cloth, ribbons, and peace medals.

Later meetings with European Americans did not go so well for the Nez Perces. In 1836, a Christian minister, Henry Spalding, and his wife, Eliza, established a at Lapwai in what is now Idaho. Spalding tried to change the Nez Perces lifestyle, including their religion. In 1847, some of the Nez Perces told the Spaldings to stop interfering with their way of life, and they attacked the mission, but no one was hurt.

, bringing their families in covered wagons on the Oregon Trail to live on lands that had been the home of the Nez Perce people, without permission or payment. The settlers also brought diseases, such as smallpox and measles, that killed many Nez Perces between 1846 and 1847.

Many pioneer families packed up their belongings and came west in wagons because they had heard that land was available. Many didnt realize that Native American peoples already lived on the land; some did not care.

THE THIEF TREATY AND WAR

CHAPTER 3

Governor Isaac Stevens was placed in charge of the new Northwest Territory, which included Nez Perce lands. He called the Walla Walla and peace.

White officials met with Native American chiefs at treaty councils to settle disagreements between the Native Americans and whites.

Governor Stevens made a new treaty in 1863 that cut the reservation to one-tenth of its size. Chief Joseph and the bands that lived on this land refused to sign the new treaty. However, Governor Stevens convinced other Nez Perce men to sign what is today called the Thief Treaty.

At first, Chief Joseph and the other bands refused to leave their home. In May 1877, however, General Oliver Otis Howard said that the Nez Perce people must leave or the U.S. Army would come after them. The Nez Perce chiefs finally decided to move to the Lapwai Reservation to avoid war. Three angry young warriors raided a settlement, however, and killed four white men. Realizing this meant war, the Nez Perces fled to White Bird Canyon. The U.S. Army followed the Nez Perces to White Bird Canyon in 1877 and attacked them, but the Nez Perce warriors badly beat the army. The Nez Perce War had begun.

DEATH AT BIG HOLE

CHAPTER 4

After the White Bird Canyon battle, the Nez Perces traveled east over the Bitterroot Mountains and camped at Big Hole, Montana. U.S. troops surprise attacked the camp and killed many Nez Perces, mostly women and children. The Nez Perces continued running, this time north toward Canada, knowing the army couldnt cross the Canadian border. General Howard asked Colonel Nelson Miles to take his troops ahead of the fleeing Nez Perces and cut them off in northern Montana.

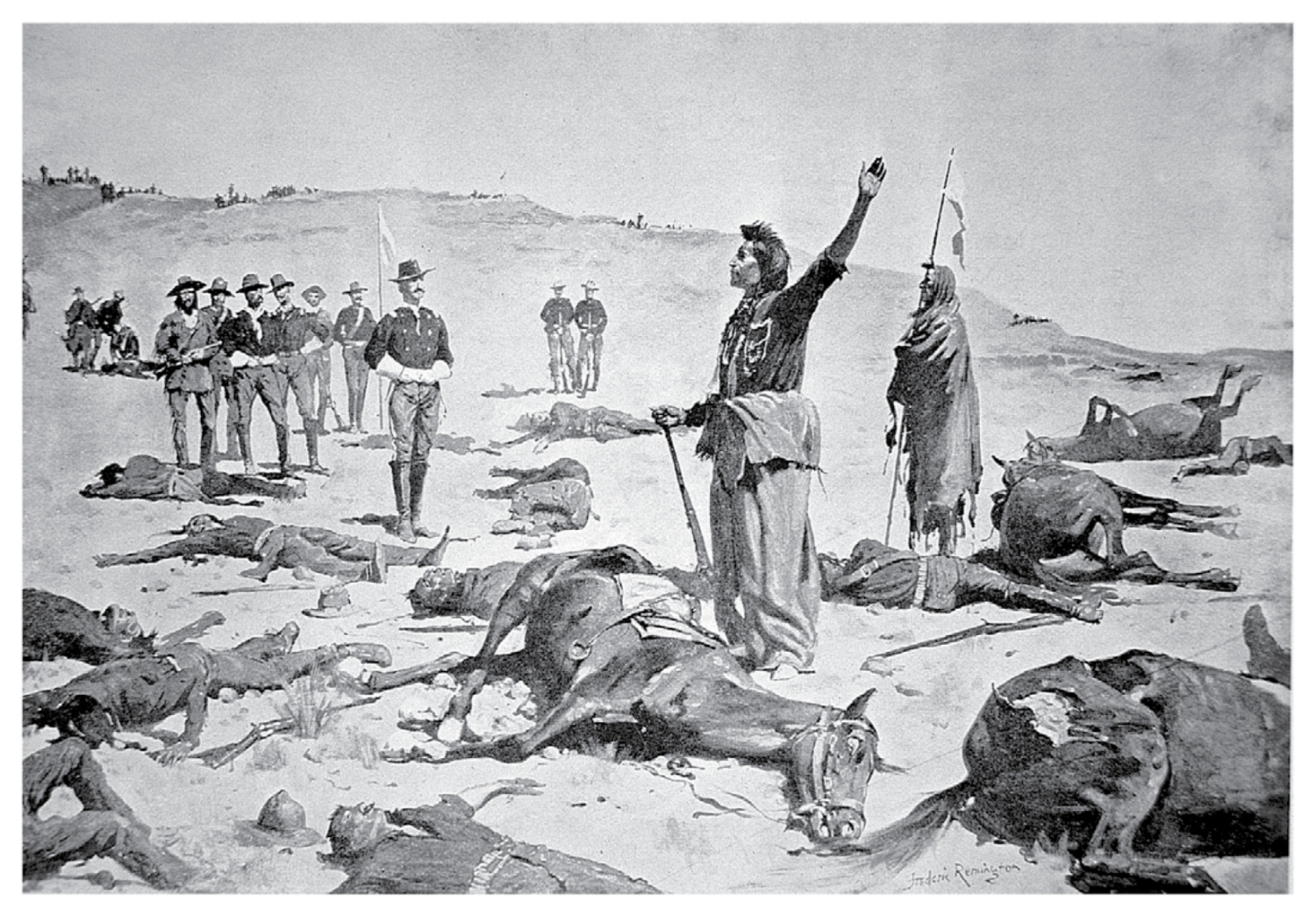

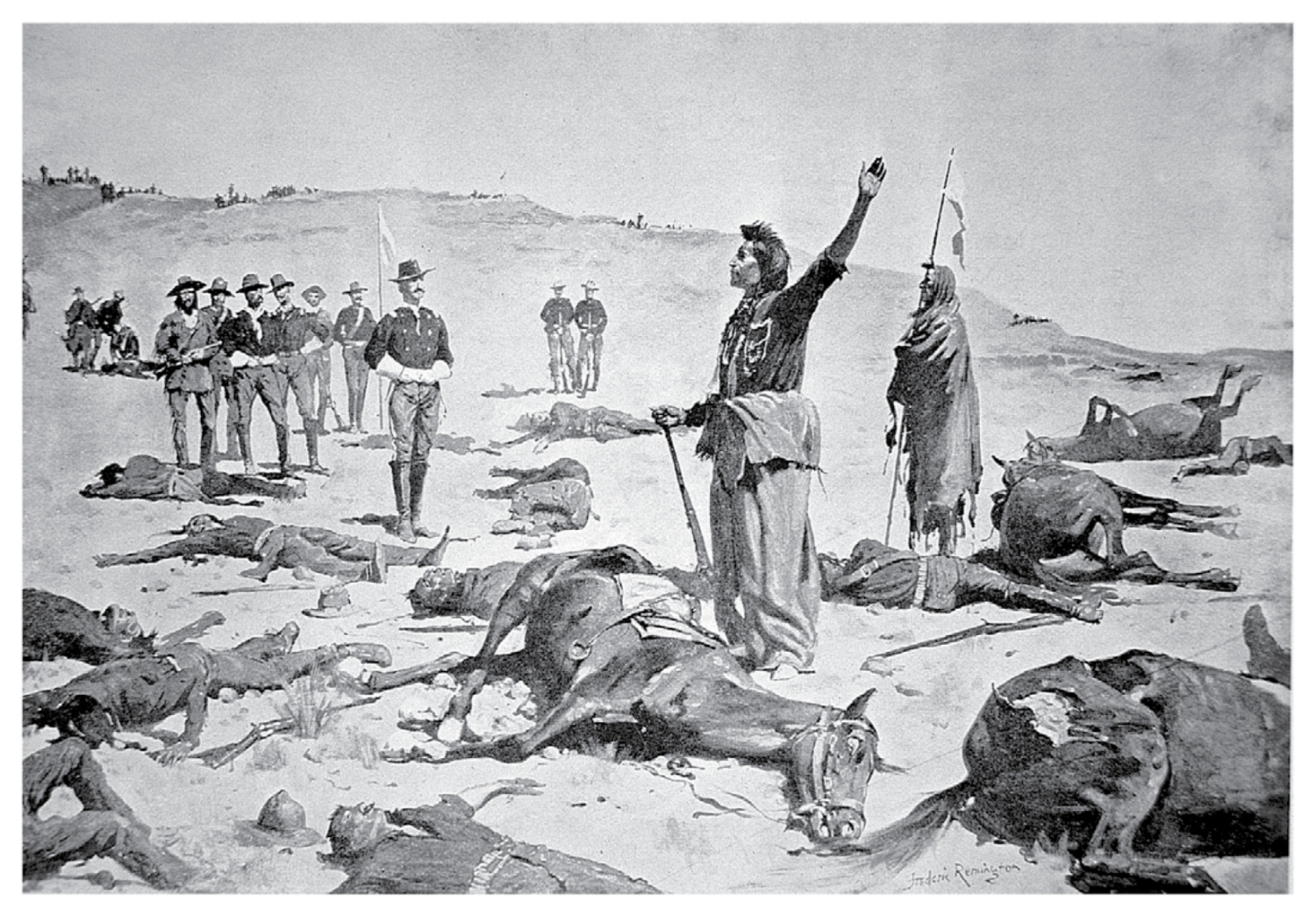

The tired and hungry Nez Perces made camp only 40 miles (64 km) from the Canadian border. General Miless troops reached them and attacked. The Nez Perces agreed to surrender if they could return to the Lapwai Reservation in Idaho.

Despite the agreement with General Miles, other army generals ignored these terms and sent 431 Nez Perces to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. In 1878, after much illness and death, they were moved to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma.

In 1885, exile finally ended. Although 431 Nez Perces surrendered in 1877, only 268 left Oklahoma in 1885. Some returned to Lapwai, but Chief Joseph and his warriors were sent to the Colville reservation in present-day Washington State, where their still live today.

At his surrender, Chief Joseph said, Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.

Big Hole Valley, Montana

TRADITIONAL CYCLES OF LIFE

CHAPTER 5

Before the mid-1800s, the Nez Perces lived in small bands and moved each season to find food. In spring, the Nez Perces caught salmon. They ate some of the fish and dried the rest to preserve it for winter. The Nez Perces hunted elk, moose, deer, rabbit, squirrel, duck, and grouse year-round.

Next page