T HE

W ISDOM

OF THE

N ATIVE

A MERICANS

T HE

W ISDOM

OF THE

N ATIVE

A MERICANS

COMPILED AND EDITED BY

KENT NERBURN

NEW WORLD LIBRARY

NOVATO, CALIFORNIA

| New World Library

14 Pamaron Way

Novato, California 94949 |

Copyright 1999 by Kent Nerburn

Cover design: Alexandra Honig

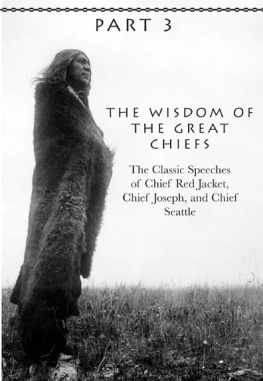

Cover and interior photo: Crying to the Spirits by Edward S.

Curtis, courtesy of the Library of Congress Text design: Mary Ann Casler

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, or transmitted in any form, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wisdom of the native Americans: includes the soul of an Indian and other writings by Ohiyesa, and the great speeches of Red Jacket, Chief Joseph, and Chief Seattle / edited by Kent Nerburn.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-57731-079-9 (alk. paper)

1. Indian philosophy North American. 2. Speeches, addresses, etc., Indian North America. 3. Indians of North America Quotations. I. Nerburn, Kent, 1946 .

E98.P5W57 1999

970.00497dc21

98-42936

CIP

First printing, March 1999

ISBN 1-57731-079-9

Printed in Canada on acid-free, partially recycled paper

Distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9

Let us put our minds together and see what kind of life we can make for our children.

Sitting Bull

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I n 1492 Columbus and his crew, lost, battered, and stricken with dysentery, were helped ashore by a people he described as neither black nor white... fairly tall, good looking and well proportioned. Believing he had landed in the East Indies, he called these people Indians. In fact, they were part of a great population that had made its home on this continent for centuries.

The inhabitants of this land were not one people. Their customs differed. Their languages differed. Some tilled the earth; others hunted and picked the abundance of the land around them. They lived in different kinds of housing and governed themselves according to differing rules.

But they shared in common a belief that the earth is a spiritual presence that must be honored, not mastered. Unfortunately, western Europeans who came to these shores had a contrary belief. To them, the entire American continent was a beautiful but savage land that it was not only their right but their duty to tame and use as they saw fit.

As we enter the twenty-first century, Western civilization is confronting the inevitable results of this European-American philosophy of dominance. We have gotten out of balance with our earth, and the very future of our planet depends on our capacity to restore the balance.

We are crying out for help, for a grounding in the truth of nature, for words of wisdom. That wisdom is here, contained in the words of the native peoples of the Americas. But these people speak quietly. Their words are simple and their voices soft. We have not heard them because we have not taken the time to listen. Perhaps now the time is right for us to open our ears and hearts to the words they have to say.

Unlike many traditions, the spiritual wisdom of the Native Americans is not found in a set of scriptural materials. It is, and always has been, a part of the fabric of daily life and experience. One of the most poignant reflections of this spiritual message is found in their tradition of oratory.

Traditionally, Indians did not carry on dialogues when discussing important matters. Rather, each person listened attentively until his or her turn came to speak, and then he or she rose and spoke without interruption about the heart of the matter under consideration. This tradition produced a measured eloquence of speech and thought that is almost unmatched for its clarity and simplicity.

Indian reasoning about governmental and social affairs was also carried on with the same uncompromising purity of insight and expression.

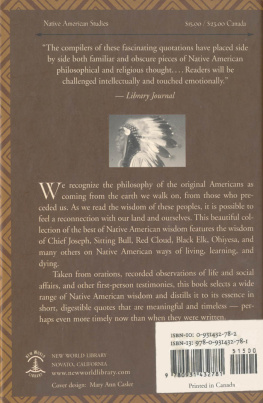

It is from these orations, recorded observations of life and social affairs, and other first-person testimonies that the materials for this book have been drawn. The wisdom has been available for some time, but much of it has been recorded only in imposing governmental documents and arcane academic treatises.

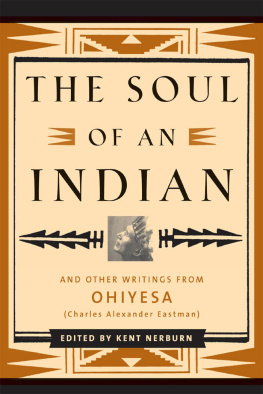

The Wisdom of the Native Americans gathers three of New World Librarys volumes of Indian oration into one collection. In addition to the short, distilled passages of Native American Wisdom, a smaller volume I compiled with Louise Mengelkoch, this book includes the thoughts of one of the most fascinating and overlooked individuals in American history: Ohiyesa, also known by the Anglicized name of Charles Alexander Eastman.

Ohiyesa was, at heart, a poet of the spirit and the bearer of spiritual wisdom. To the extent that he dared, and with increasing fervor as he aged, he was a preacher for the native vision of life. It is my considered belief it is his spiritual vision, above all else, that we of our generation need to hear. We hunger for the words and insights of the Native American, and no man spoke with more clarity than Ohiyesa.

Ohiyesa was born in southern Minnesota in the area now called Redwood Falls in the winter of 1858. He was a member of the Dakota, or Sioux, nation. When he was four, his people rose up in desperation against the U.S. Government, which was systematically starving them by withholding provisions and payment they were owed from the sale of their land.

When their uprising was crushed, more that a thousand men, women, and children were captured and taken away. On the day after Christmas in 1862, thirty-eight of the men were hanged at Mankato, Minnesota, in the greatest mass execution ever performed by the U.S. Government. Those who were not killed were taken to stockades and holding camps, where they faced starvation and death during the icy days of the northern winter.

Ohiyesas father, Many Lightnings, was among those captured.

Ohiyesa, who was among those left behind, was handed over to his uncle to be raised in the traditional Sioux manner. He was taught the ways of the forest and lessons of his people. He strove to become a hunter and a warrior. Then, one day while he was hunting, he saw an Indian walking toward him in white mans clothes. It was his father, who had survived the internment camps and had returned to claim his son.

During his incarceration, Many Lightnings had seen the power of the European culture and had become convinced that the Indian way of life could not survive within it. He despised what he called reservation Indians who gave up their independence and tradition in order to accept a handout from the European conquerors.

He took Ohiyesa to a small plot of farming land in eastern South Dakota and began teaching him to be a new type of warrior. He sent him off to white schools with the admonition that it is the same as if I sent you on your first warpath. I shall expect you to conquer.

Thus was born Charles Alexander Eastman, the Santee Sioux child of the woodlands and prairies who would go on to become the adviser to presidents and an honored member of New England society.