Contents

Copyright 2017 by David M. Buerge

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by Sasquatch Books

Editor: Gary Luke

Production editor: Em Gale

Design: Tony Ong

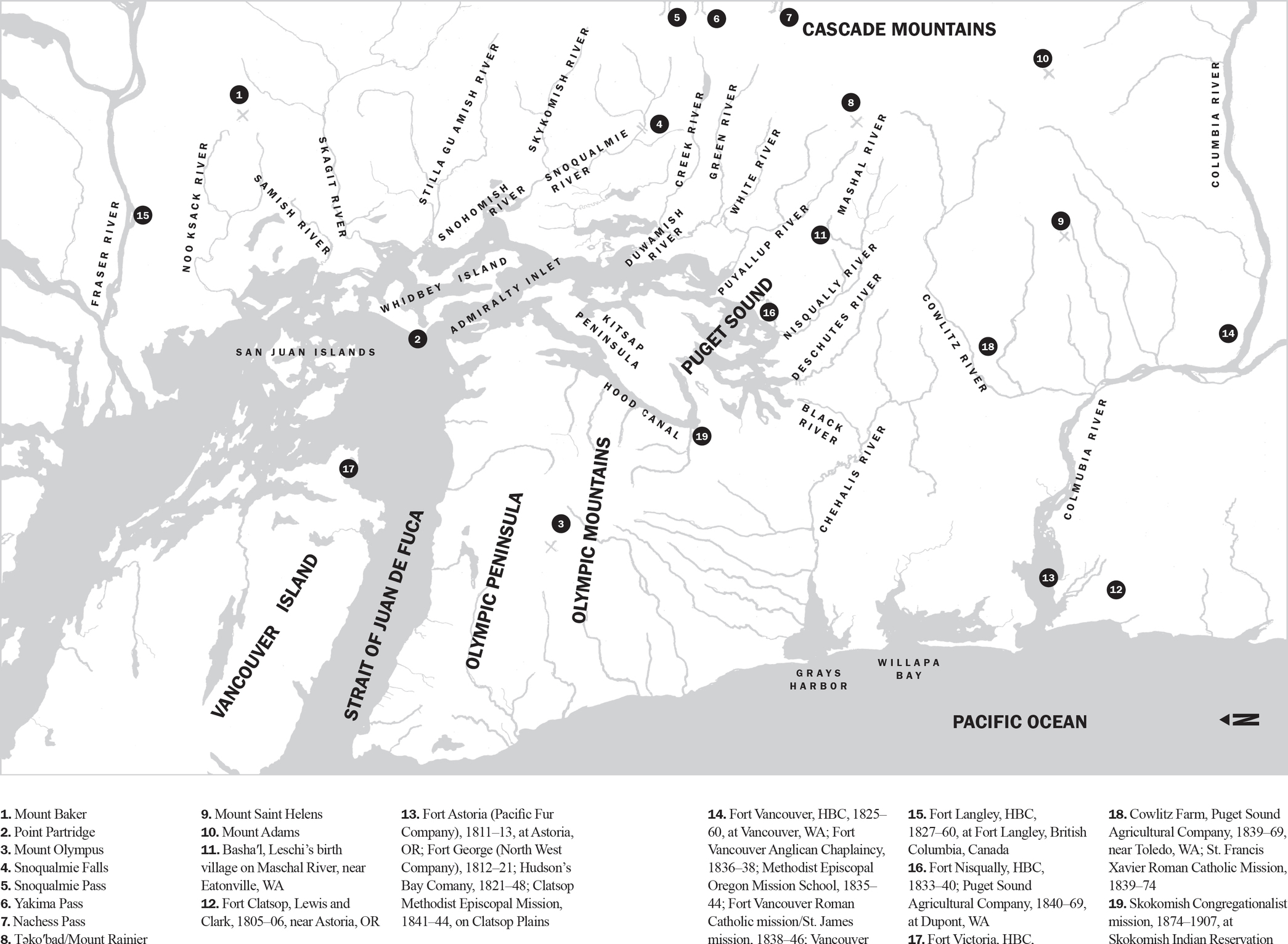

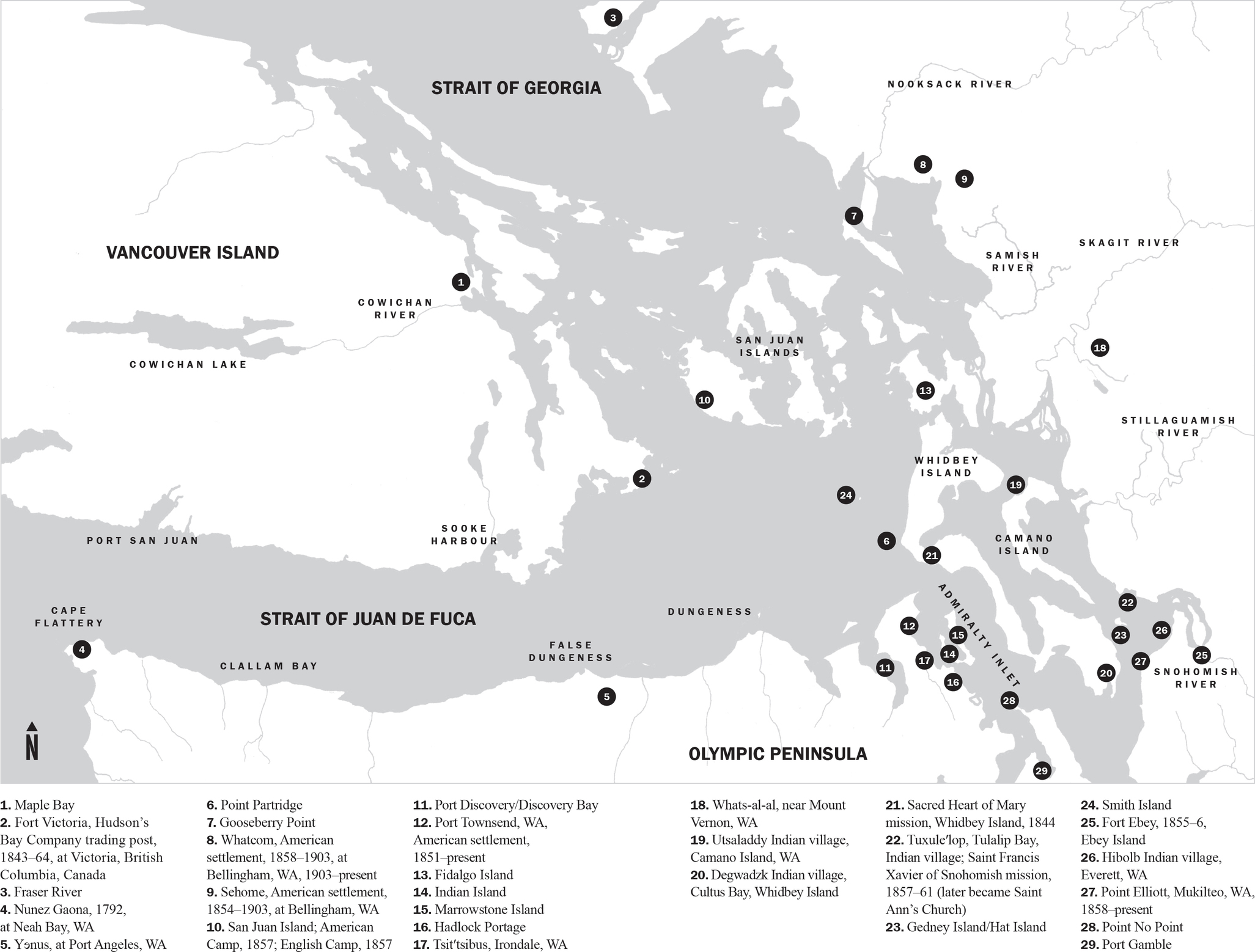

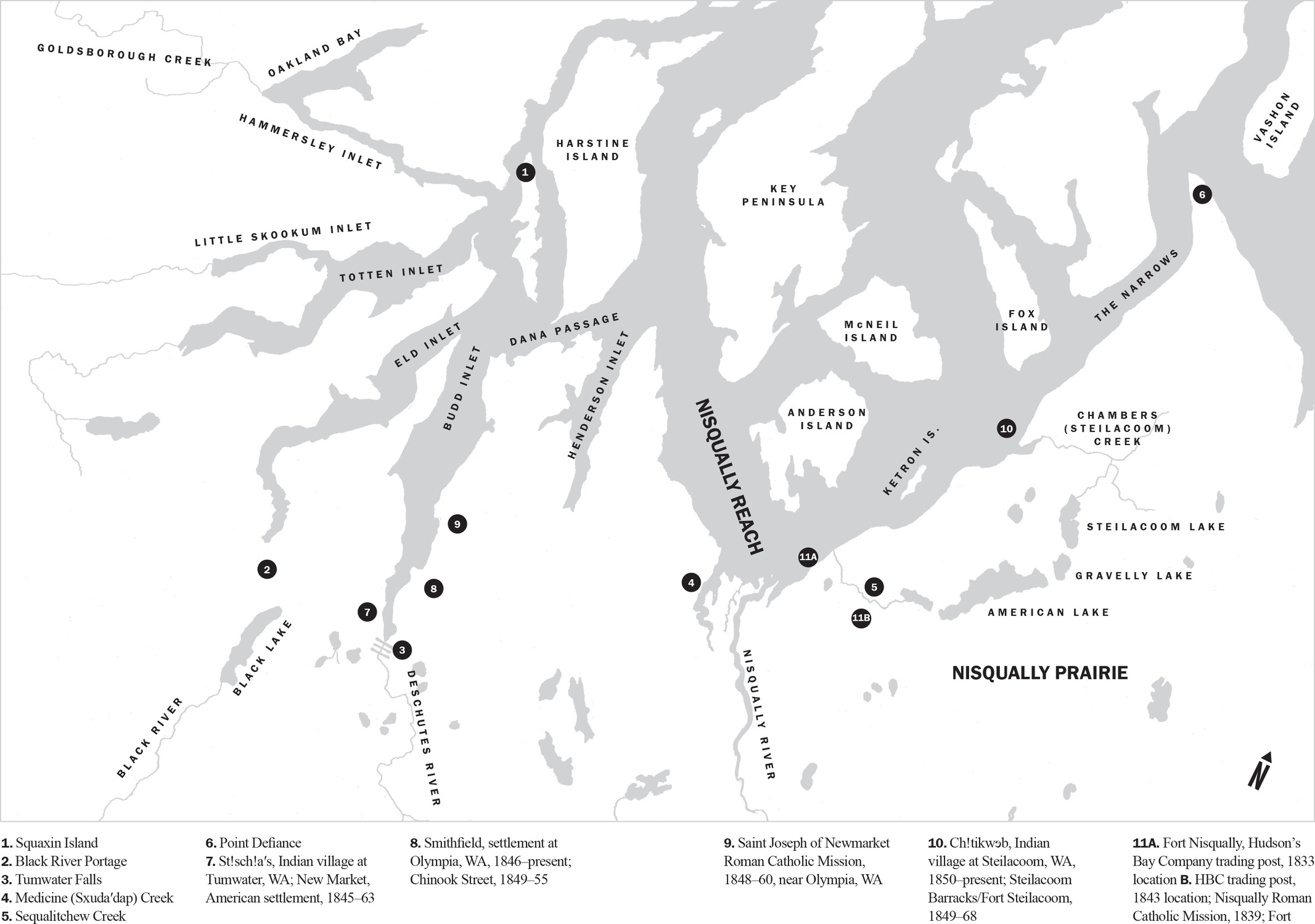

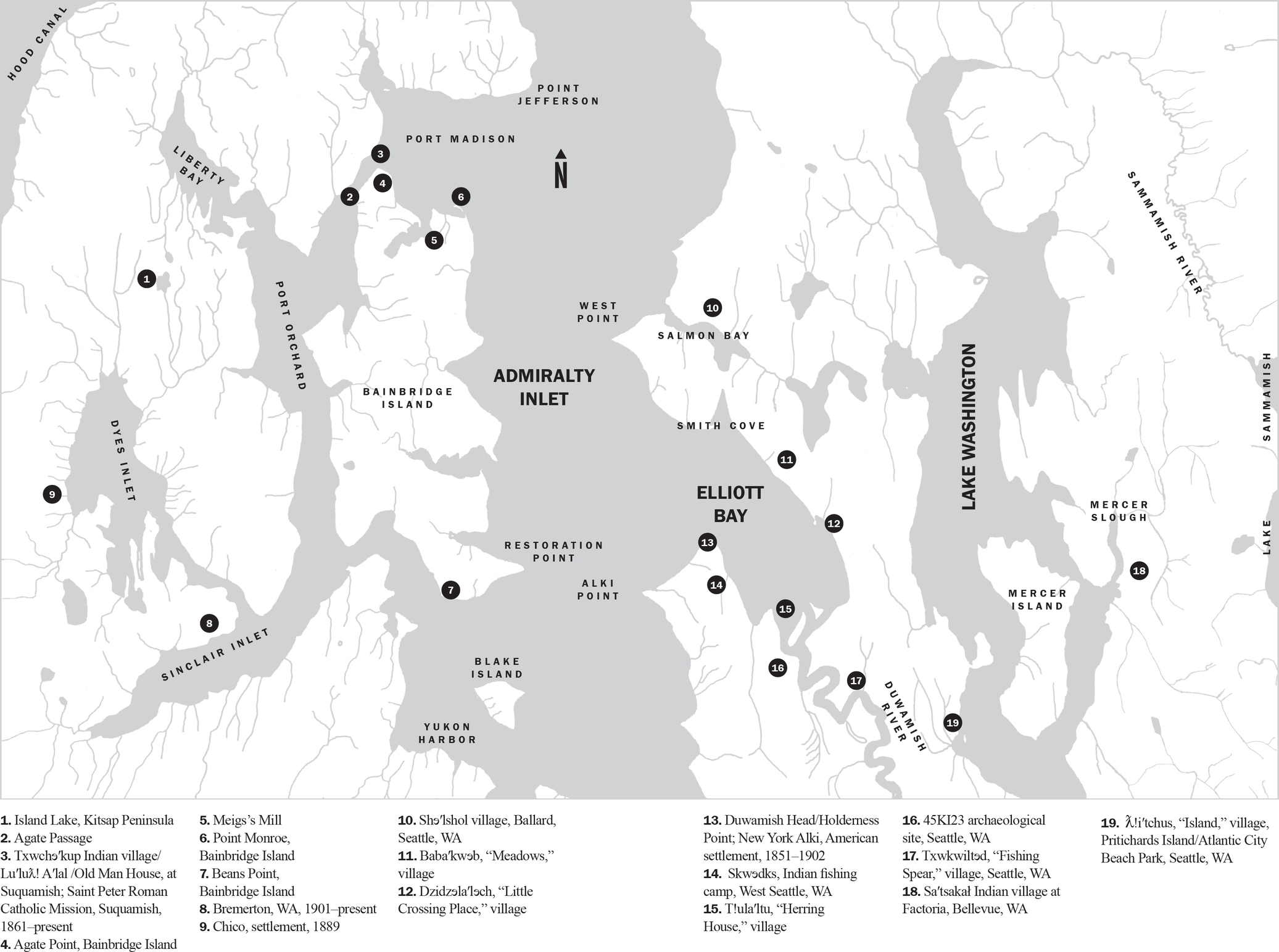

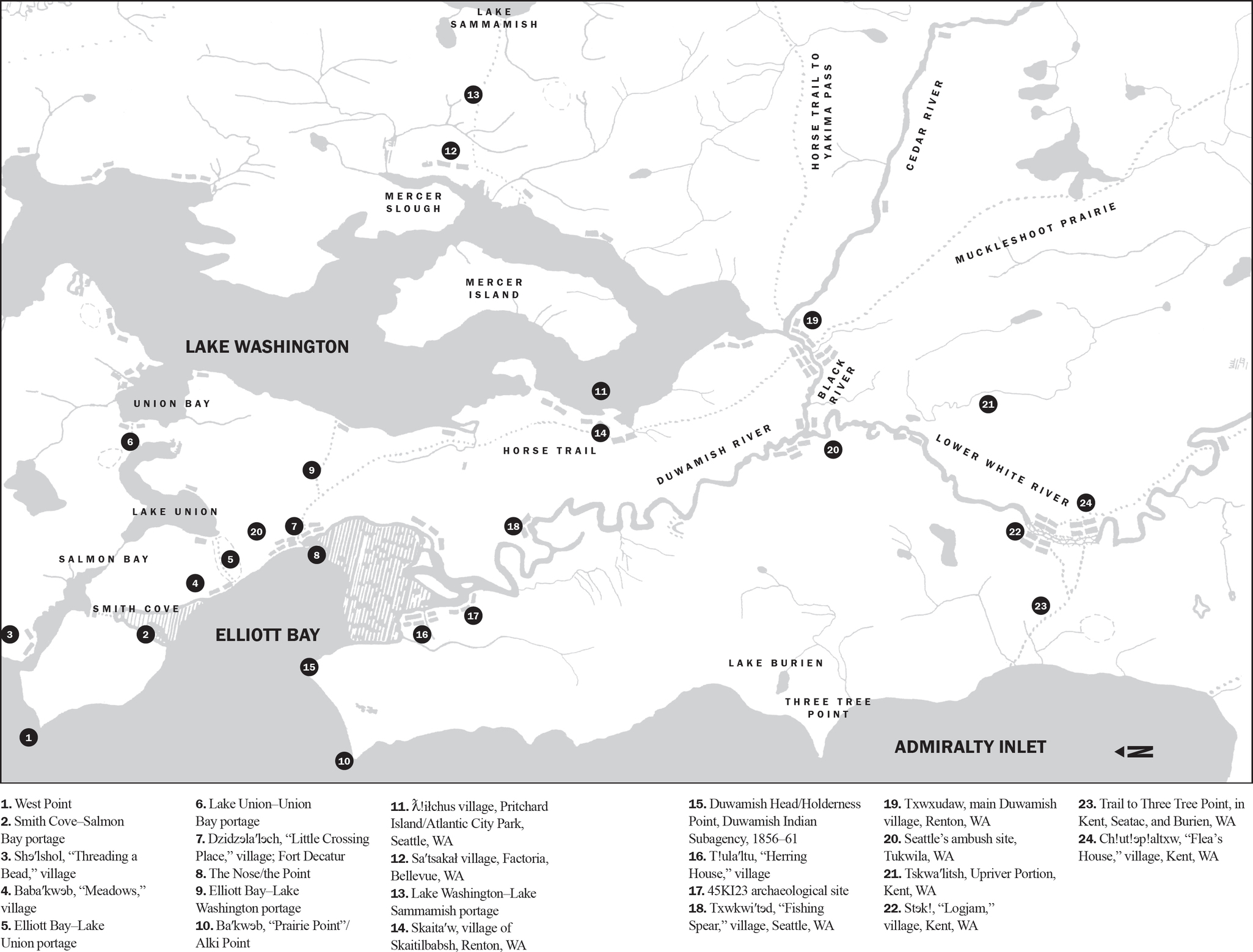

Maps: David M. Buerge

Copyeditor: Elizabeth Johnson

Cover image of Chief Seattle: Courtesy of the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, catalog number 1994-1/5.

Cover image of Seattle: Courtesy of the Library of Congress, 75696660

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Buerge, David M., author.

Chief Seattle and the town that took his name : the change of worlds for the native people and settlers on Puget Sound / David M. Buerge.

Seattle, WA : Sasquatch Books, 2017.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

LCCN 2017004912 | ISBN 9781632171351 (alk. paper)

LCSH: Seattle, Chief, 1790-1866. | Suquamish IndiansBiography. | Seattle Region (Wash.)Biography. | Puget Sound Region (Wash.)Biography.

LCC E99.S85 B84 2017 | DDC 979.7004/97940092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017004912

ISBN9781632171351

Ebook ISBN9781632171368

Sasquatch Books

1904 Third Avenue, Suite 710

Seattle, WA 98101

(206) 467-4300

www.sasquatchbooks.com

custserv@sasquatchbooks.com

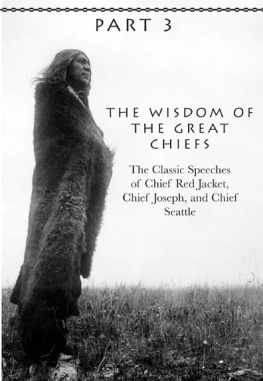

() E. L. Sammis photograph of Seattle, chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish people, cofounder of the city of Seattle, taken in 1864.

v4.1

a

This work is dedicated to Cecile Hansen, chairwoman of the Duwamish Tribe, who has devoted her life in the effort to gain federal recognition for her people, the first signatories of the Treaty of Point Elliott.

Holy Seattle, thrice born and

Always among your people;

Visit these words well meant,

And greet us again, birds

Homing under the eaves

In the house of your name.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Prehistory to 1792

There was a time when our people covered the whole land.

CHAPTER TWO

To 1832

Why should I murmur at the fate of my people?

CHAPTER THREE

To 1847

Your God seems to us to be partial.

CHAPTER FOUR

To 1852

I am glad to have you come to our country.

CHAPTER FIVE

To 1854

How then can we become brothers?

CHAPTER SIX

To 1856

The Great Chief above who made the country made it for all.

CHAPTER SEVEN

To 1858

I want you to understand what I say.

CHAPTER EIGHT

To 1866

Shake hands with me before I am laid in the ground.

CHAPTER NINE

To 1887

Dead, did I say?

CHAPTER TEN

To the Present

The dead are not altogether powerless.

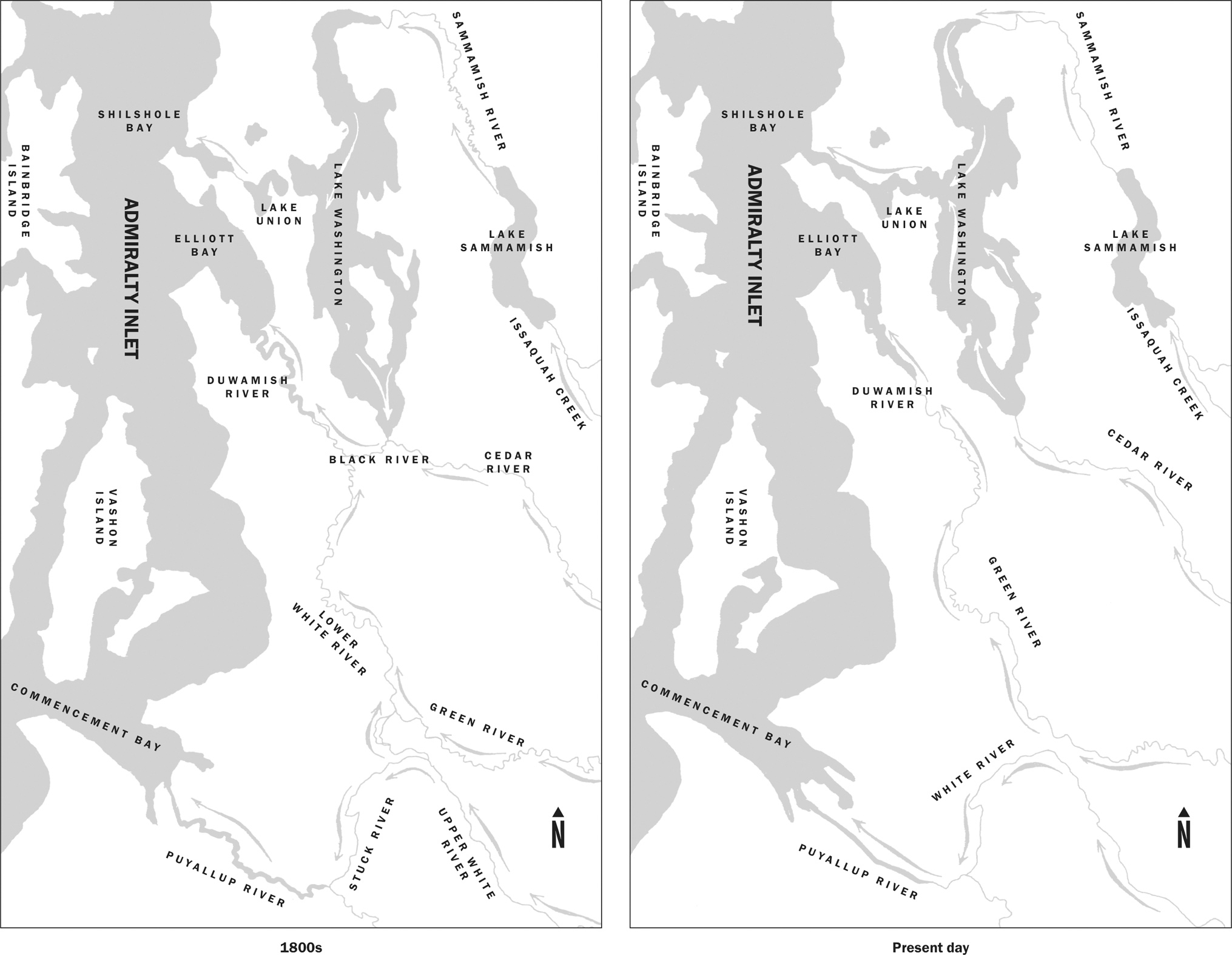

DUWAMISH WATERSHED, ANCIENT AND MODERN

Seattles burial site at Suquamish. The story poles carved by Squaxon tribal artist Andrea Wilbur-Sigo replaced a framework holding aloft carved canoes erected during the 1976 national bicentennial.

INTRODUCTION

January days dawn typically cold and gray on Seattles rain-slick streets. Near Pioneer Square, the historical heart of the city, where potholed asphalt slopes down to Elliott Bay, the bluffs of a small island once gave way to a gravelly beach. The island, its bluffs, and the beach have been buried for over a century beneath urban fill, but the slope still mirrors that of the old landscape. In a place where written history does not go deep, the power and dynamism of the modern city is a thin blanket resting on the lineaments of an older and largely forgotten world.

Out on the bay container ships lit up like billboards ride at anchor waiting to deliver cargoes from Asia, and ferries cross steely waters, looking like so many illuminated palaces. Around me, streetlights still shine, but the city already thrums with the low rumble of traffic and construction. Workers in yellow rain gear and residents holding their coats close hurry, heads down, through drizzle to work, but I sit in my car on my own errand. Today is January 12. On that day in 1854, in colder, clearer weather, over one thousand native people disembarked from scores of canoes hauled up on the beach and gathered around driftwood fires. Joining them were about one hundred American settlers, new neighbors only recently arrived.

If I could take you back to this same spot that January day, we would find ourselves, absent the fill, balancing unsteadily atop the bark-shingled roof of the Seattle Exchange, a log cabin store built with native help for David Swinson Maynard, a Vermont doctor with a medical degree from Middlebury College, who had arrived when the place was an Indian village. Everyone had assembled to hear Isaac Ingalls Stevens, the first governor of Washington Territory, announce plans for upcoming treaties with the Indians.

After Stevens made a brief speech, a large old Indian with a powerful voice stepped forward. In the west, a pale moon hung openmouthed in the sky over the Olympic Mountains. In the hybrid settlement bearing his name, Chief Seattle spoke compellingly about change and continuity, love and loss, justice, kindness, and the power of the dead.

Another pioneer doctor, Henry Allen Smith from Ohio, penciled snatches of what he heard in his diary. Edited and published thirty-three years later, what Smith wrote is considered to be one of the greatest orations ever delivered by a Native American. But the anniversary of that speech, which I mark this morning, passes without notice. Indeed, none of its anniversaries have ever been noted. How is this possible?