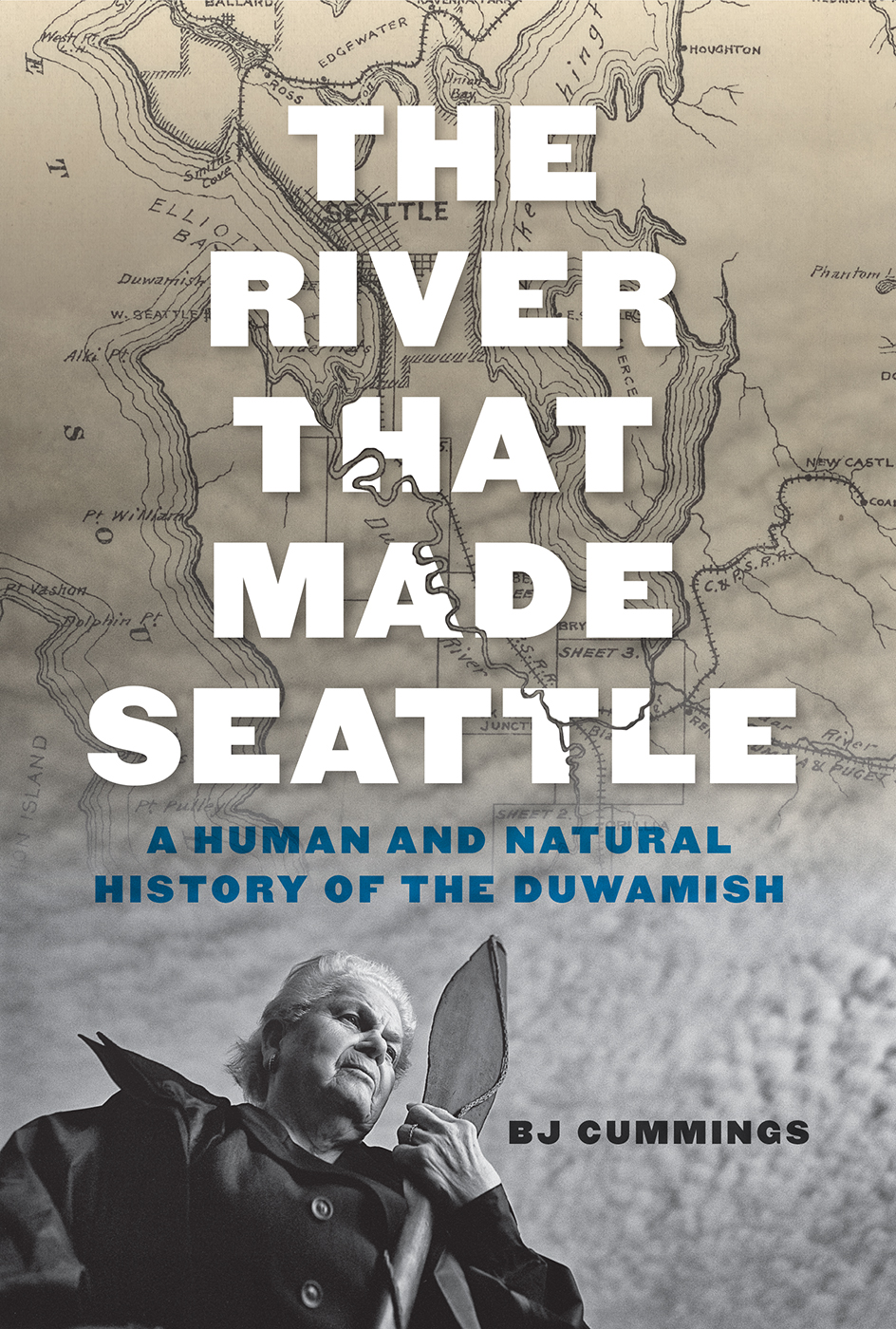

THE RIVER THAT MADE SEATTLE

THE RIVER

THAT MADE

SEATTLE

A HUMAN AND NATURAL HISTORY

OF THE DUWAMISH

BJ Cummings

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle

The River That Made Seattle was supported by a generous grant from the Tulalip Tribes Charitable Fund, which provides the opportunity for a sustainable and healthy community for all.

Copyright 2020 by the University of Washington Press

Design by Katrina Noble

Composed in Adobe Caslon Pro, typeface designed by Carol Twombly

24 23 22 21 205 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

uwapress.uw.edu

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA ON FILE

ISBN 978-0-295-74743-9 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-295-74744-6 (ebook)

Cover design: Katrina Noble

Cover illustrations: (photograph) Ann Rasmussen, great-granddaughter of Quio-litza (aka Ann Kanum), holding the familys heirloom canoe paddle. Courtesy of Jeff Corwin. (map) Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. Vicinity map, Duwamish River & its tributaries, Washington New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 24, 2020. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/640f77e0-2c61-0136-6f21-0bfd557ad2c4.

Frontispiece: Duwamish Waterway. Courtesy of Tom Reese.

The paper used in this publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI z39.481984.

To the people of the Duwamish Riverpast, present, and future

We are still here.

CECILE HANSEN, CHAIRWOMAN, DUWAMISH TRIBE

Its a river, not a waterway.

TIM OBRIEN, RESIDENT/ACTIVIST, GEORGETOWN, SEATTLE

CONTENTS

An Environmental and Cultural Renaissance,

2000 to the Present

PREFACE

The Duwamish is our river. Whether you live in my hometown of Seattle or in Chicago, Newark, Mobile, Des Moines, or Los Angeles, you have a river with a story, and that story resembles the one in this book. The details vary, but the broad strokes are strikingly consistent.

Across America, our nation has corralled and manipulated waterways for the prosperity of our cities, farms, and industries. We have commandeered their channels as repositories for our waste, reservoirs for our irrigation systems, and raw energy for our power plants. We have built our urban centers, expanded our agriculture, and fueled our industrial growth by exploiting our rivers resources. In doing so, we have enriched ourselves. In every instance, we have also caused suffering and deprivation.

It is well understood that we have sacrificed whole populations of aquatic birds, fish, mammals, and plants by altering our rivers. But we have also impoverished entire populations of Indigenous peoples of the Southwest who rely on the cultural and subsistence resources of the Rio Grande River; low-income families who fish to survive on the Anacostia River in Washington, DC; and industrial fenceline communities in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati who live next to polluting factories on the Ohio River. The choices we have made about how we use our rivers reflect the values of the governing bodies of our cities and townships at the moments when those choices were made. Few of us know much about that history.

Without knowing our history, we cannot understand how it has influenced the river communities we know today. Nor can we understand historys influence on the choices we continue to make. Without knowing our history, we are doomed, as the saying goes, to repeat itor, worse, to exacerbate its harms.

Increasing conflicts over water resources in the United States in recent years are refocusing attention on the stories of our rivers and their people. Our nations history, including the colonial-era appropriation of North Americas waterwaysoften by forceis showing its stress lines. In the arid West, alliances of Native tribes and environmentalists are being pitched against the interests of farmers as some states consider dismantling century-old dams. On the Sioux Nations Standing Rock Reservation, tribal leaders led a nine-month standoff with Energy Transfer Partners and the State of North Dakota in 2016 in an attempt to protect the nearby Missouri River from pipeline spills. And in British Columbia, Wetsuweten hereditary chiefs are leading a fight to prevent a pipeline from crossing their autonomous lands, in part to protect the Morice River.

What do these movements and eruptions of civil unrest have in common with the struggle for control over water resources on the Duwamish and hundreds of other rivers nationwide? In many of these watersheds, communities are more quietly, though no less desperately, fighting similar threats to their health, culture, and livelihood.

By some accounts, Seattles Duwamish River has emerged as an example of best practices in restoring the environment and promoting social justice while cleaning up past pollution. In other circles, Seattles river cleanup is seen as a farce, driven by a powerful confluence of government and industry forces aligned against tribal and immigrant communities. The truth, and the lessons we can learn from the Duwamish case, reflects a bit of both. Grounded in colonial appropriation and fueled by contemporary racism and anti-immigrant sentiment, the treatment of the Duwamish River and its communities today leaves much to be desired, yet it surpasses the low standards set for river restoration and cleanup across much of the country.

The Duwamish story is one case study in the national effort to express our values in the way we treat our rivers and their people. The Standing Rock battle cryMni wiconi, or Water is lifecaptures the threat many communities perceive in sacrificing our rivers for national progress and financial gain. As we begin to restore riverbank habitat and to scrub decades of chemical waste from our river bottoms, we have the opportunity to act in accordance with our values. If we do enough to create a result pleasing to the eye, but insufficient to protect the health of our riverdependent communities, that decision will speak volumes about the classism and racism that underpin it. And if we demand a pristine restoration of a romanticized past, we may disenfranchise exactly those people from whom our rivers were appropriated in the first place.

Collaboration, respect, and justice are core values that we may or may not choose to guide our efforts at environmental restitution, but they are most certainly the only path forward if we want to ensure that our actions make the Duwamish, Hudson, Cuyahoga, Mississippi, and Potomac into rivers that serve all the people who live, work, fish, play, and pray in and along their waters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I extend my deepest gratitude to the people who shared their personal and family stories with me as I explored the experiences of the Duwamish Rivers Native, immigrant, and industrial communities. I am eternally grateful to James Rasmussen, Virginia Nelson, and the extended Kanum-Tuttle family for sharing their family albums, records, heirlooms, and histories as I followed their Duwamish family through seven generations of interactionsoften painfulwith the watersheds settler families and colonial governments. I also owe many thanks to Cecile Hansen and Ken Workman, who contributed valuable insights into their own experiences and those of their Duwamish ancestors. Other people who made invaluable contributions to this book include Louise Jones-Brown of the Maple family, Suzanne Hittman of the Desimone family, the extended Hamm and Medina families, Marianne Clark, Carmen Martinez, David Yamaguchi, Liana Beal, Paulina Lopez, Peter Quenguyen, and Sophorn Sim. Their stories of immigration and honest reflections about the imprint their families made on the riverand vice versawere critical to painting the watersheds portrait.