Writing the Ancestral River

Writing the Ancestral River

A biography of the Kowie

Jacklyn Cock

Published in South Africa by:

Wits University Press

1 Jan Smuts Avenue

Johannesburg, 2001

www.witspress.co.za

Copyright Jacklyn Cock 2018

Published edition Wits University Press 2018

Photographs Copyright holders 2018

Poems Copyright holders 2018, used with permission

Cover images:

Top: Map of the country between the Kowie and the Chalumna rivers, Caesar C. Henkel, 1876. University of Cape Town Libraries, Historical Map Collection.

Bottom: Kowie, looking seaward, lithograph by F. Jones from painting by Thomas

Bowler, hand coloured. Cory Library/Africa Media Online.

First published 2018

http://dx.doi.org.10.18772/12018031876

978-1-77614-187-6 (Print)

978-1-77614-188-3 (Web PDF)

978-1-77614-189-0 (EPUB)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, Act 98 of 1978.

All images remain the property of the copyright holders. The publishers gratefully acknowledge the publishers, institutions and individuals referenced in the captions for the use of images. Every effort has been made to locate the original copyright holders of the images reproduced here; please contact Wits University Press in case of any omissions or errors

Project manager: Hazel Cuthbertson

Copy editor: Russell Martin

Proofreader: Lisa Compton

Indexer: Tessa Botha

Cover design: Peter Bosman, Guineafolio

Typesetter: Newgen

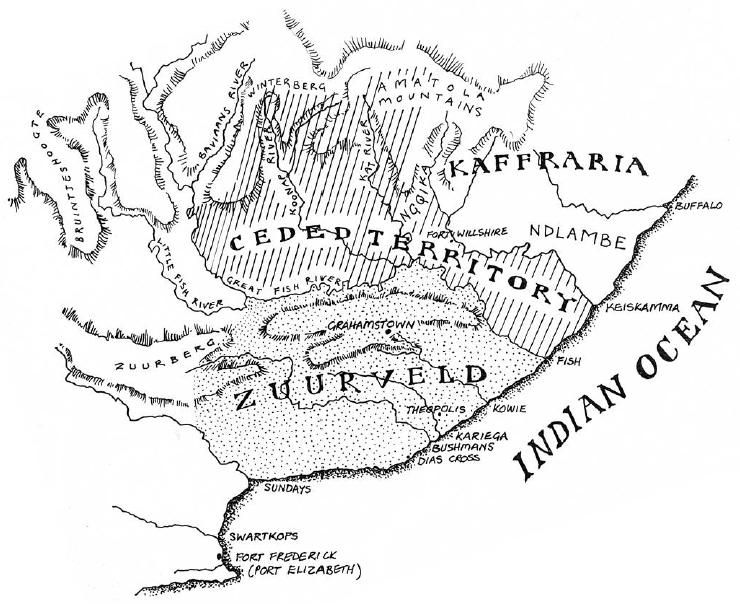

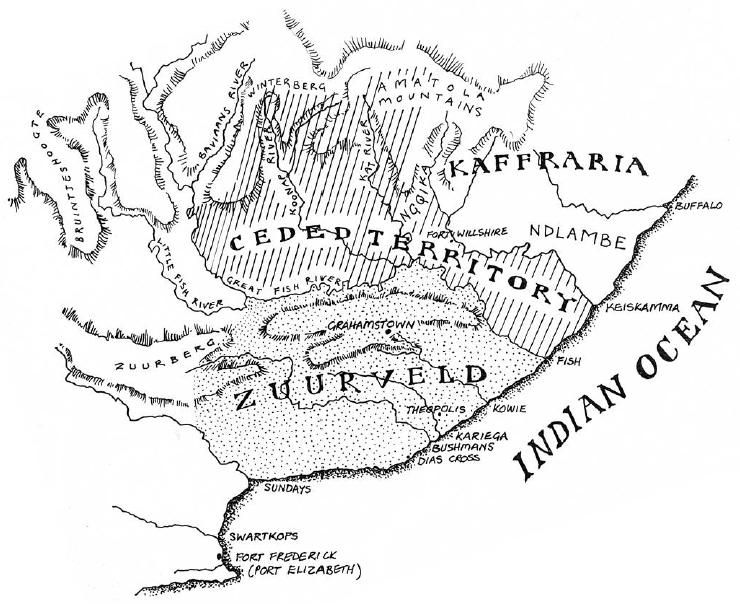

The Kowie River runs through the centre of what was once called the Zuurveld, originally defined in the early 1800s as the area between the Bushmans River in the west and the Fish River in the east. The boundary was later extended further west to the Sundays River (Map by Hazel Crampton, from The Sunburnt Queen, Jacana, 2004).

Contents

Acknowledgements

T his book draws heavily on the published work of many historians with far more knowledge and insight than I possess. I have learnt a great deal particularly from Tim Keegan, Basil Le Cordeur, Jeff Peires, Clifton Crais and especially Julie Wells, whose brilliant analysis of the Battle of Grahamstown fired my imagination. Walking with her on occasions through the forests of the Fish River valley and the desolate coast of Cove Rock has deepened my appreciation of the history of the Xhosa. The book has also benefited from the help of numerous people including all those who gave up their time, agreed to be interviewed, and trusted me with their opinions and experiences. I am particularly grateful to Kate Rowntree, who helped me find the source of the Kowie River, Chris Mann, whose poems about the river have been inspirational, and Helen Bradford, who gave much advice and spent hours in the Cape Town archives looking for photographs for this book. Thanks also to Candace Feit, Jo and Jaxon Rice and David Stott for the wonderful photographs, and all the other friends who read the whole or parts of the manuscript and commented helpfully, including Eddie Webster, David Fig, Glenn Moss, Georgina Jaffe, Malvern van Wyk Smith, Patricia Milliken, Nicholas Scarr, Michelle Williams, Vishwas Satgar, Dorothy Driver, Karl von Holdt, Tony Dold, Judith Hawarden and Kathie Satchwell. Several friends helped with difficult technical issues, especially Karin Pampallis, Brittany Kesselman and Ingrid Chunwill. I am also very grateful for the comments of two anonymous reviewers, which were extremely helpful, to my editor, Russell Martin, and to Hazel Cuthbertson and Roshan Cader of Wits University Press.

Motivations

R ivers have the power to connect us to nature, to our past and to our collective selves. They sustain life, inspire poetry and fire our imaginations. As the young sailor in Joseph Conrads Heart of Darkness expressed it, they carry with them the dreams of men, the seeds of commonwealth, the germs of empires. Conrad clearly had in mind the great river highways such as the Amazon, the Congo, the Mississippi, the Mekong, the Thames and the Yangtze. This book tells the story of what is in comparison a little estuarine river, which nevertheless raises large questions.

This river, the Kowie, is not a major waterway and has not been the subject of any scholarly attention. While located in a war-ravaged frontier area, it was never an official frontier and it played a humbler role in South African history than the rivers which the colonial authorities used to mark the changing borders of the Cape Colony: the Bushmans, Fish, Keiskamma and Kei. The area was an open frontier until 1778, when the Fish was declared the official limit of the Cape Colony. Most importantly for this book, the Kowie River runs through the centre of the Zuurveld, the area first bounded by the Fish to the east and the Bushmans to the west.

This was an area of blending and mixing, a meeting point not only of river and sea, of fresh and salt water, but of very different people, identities and traditions that have shaped South African history: Khoikhoi herders, Xhosa pastoralists, Dutch cattle farmers and British settlers. Their interaction often involved intense and violent encounters and still today there are contesting claims and traditions relating to the land, the fertile sour-grass hills and plains of the Zuurveld, now known as Ndlambe Municipal Area, one of the poorest parts of South Africa.

The original inhabitants of the Zuurveld were the Khoikhoi, often contemptuously called Hottentots by the settlers. These indigenous people were the first to experience what has been described as the violent, even genocidal process of colonial expansion in the late eighteenth century as Dutch farmers appropriated their land, their cattle and their power. In 1774 the Dutch government at the Cape ordered that the whole race of Bushmen and Hottentots who had not submitted to servitude be seized or extirpated.

Rivers like the Kowie were important in Khoikhoi identity. According to Ensign Beutler, whose expedition of 1752 passed through the area, the Khoikhoi do not know of what people they are: they name themselves only after the rivers by which they live.

Although it is clear from Beutlers journal that there were no Xhosa living west of the Keiskamma at the time of his 1752 expedition, the Dutch explorer Colonel Robert Gordon found many Xhosa living in the Zuurveld when he visited the area in 1777. By this time, Dutch trekboers, or pastoralists, were already encroaching upon Xhosa and Khoi territory, and within a few years the Zuurveld became marked by struggles over access to land and cattle. The clashes formed the start of what has been called a Hundred Years War between the Xhosa and the colonists, who, after the Cape was taken over by the British, could call on the support of the British army.

The thick bush of the Kowie and other river valleys was the scene of violent clashes during these wars of dispossession. At that time the riverbanks were thick with ancient cycads, wild crane flowers, gigantic yellowwood trees and shady white milkwoods. The dense vegetation, the thickly forested valleys and deep ravines, the towering trees, creepers and vines, all offered hiding places to the Xhosa, for whom this was a familiar landscape. It also made movement difficult for the British soldiers. During one war the Gqunukhwebe showed what could be done with the river beds of lower Albany. Using the banks as parapets, they exposed only their heads They were able to hide for long periods under water, their nostrils emerging under cover of the reeds at the rivers edge. Otherwise they hid in trees, in antbear holes and in caves. The Kowie was one of the rivers used in this way.

Next page