The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my father, Peter, and my son, Nathaniel.

And also, for Jack Macrae, good friend and editor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

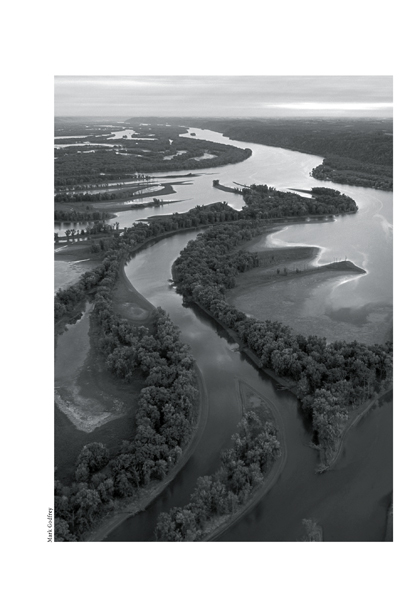

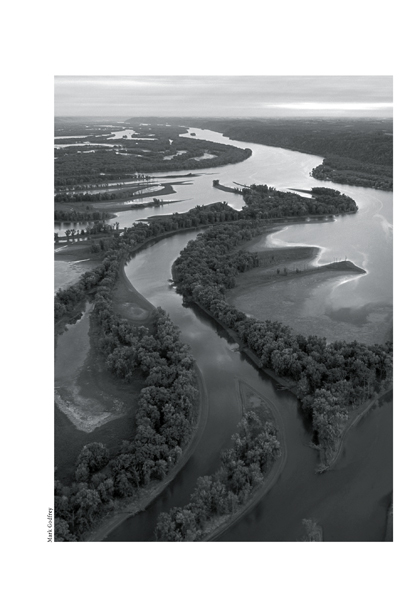

All of my previous books are dedicated to Nina Bramhall, and though her name is not at the front of this book, she is still foremost among those who deserve my gratitude. Jack Macrae at Henry Holt also bears much responsibility for this book emerging from the low fog of its morning hours. My various traveling companions in the watershed, both those who came along by plan and those I met here and there along the way, deserve my thanks. There are too many of these to name, but Natty Schneider, Loren Demerath, Clayton Omer, Al Andry, and Pat Schneider come to mind. The guys at Boyden and Perrin who fixed my outboard motor on short notice are remembered, as is the fellow in Louisville who had a replacement propeller for me. Thanks too to the Schwabs of Tidiute, Pennsylvania; the Omers of Louisville, Kentucky; the McCraws of Memphis, Tennessee; Cory Werk on the Bayou Teche; Hoppie of Hoppies Marina in Imperial, Missouri; Lionel Sutton; Will Dana and Brad Weiners at Mens Journal ; Barbara Ireland and especially Wendy and Boatner and the rest of the Riley clan of New Orleans. Thanks as well to all the friendly lock operators of the Army Corps, the dock personnel, and the many historians, archaeologists, and writers whose work is mentioned in the source notes. Thanks also to my agent, David Kuhn, to Courtney Reed, Muriel Jorgensen, Kelly Too, and the rest of the folks at Henry Holt. Early readers of parts or all of the manuscript include various Schneiders and Bremhalls, Bee Ridgway, Ward Just, and Loren Demerath. Thanks Quinn Brady for the marvelous maps and Mark Godfrey of the Nature Conservatory for the beautiful photo on the title page.

Last, I am grateful to the United States Congress, which in 1971 functioned long enough to override Richard Nixons veto of the Clean Water Act by a wide, bipartisan margin.

CONTENTS

The American Watershed

BOOK ONE:

Continents Collide, Glaciers Recede, Mastodons Bellow, and Humans Arrive

BOOK TWO:

The Rise and Fall, and Rise and Fall, and Rise of Native America

BOOK THREE:

The Spanish Exit, the French Arrive, the Iroquois Take Action

BOOK FOUR:

The English Enter, the French Exit, the Iroquois Negotiate, and the Americans Take Over

BOOK FIVE:

Flatboats and Keelboats, Steamboats and Showboats, Songsters and Soul Drivers

BOOK SIX:

Lincoln and Davis, New Orleans and Vicksburg, Victory and Defeat

BOOK SEVEN:

Floods Rise, Levees Rise, Dams Rise, while Mountains Fall and Grasses Sink

He is blessed over all mortals who loses no moment of the passing life in remembering the past.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

One cannot see too many summer sunrises on the Mississippi.

MARK TWAIN

PROLOGUE

THE AMERICAN WATERSHED

It doesnt matter from what perspective you look at the river in the middle of the continentgeologically, ecologically, prehistorically, ethnographically, economically, industrially, socially, musically, literarily, culturally, or over the gunnels of your canoe midstream. Its impossible to imagine America without the Mississippi. The rivers history is our history.

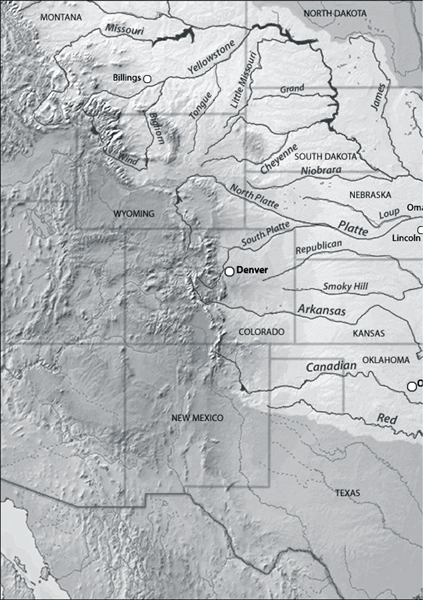

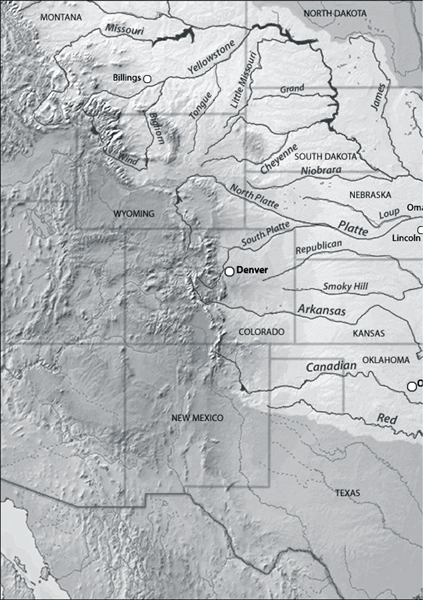

Similarly, just as a tree without branches and roots is merely lumber, it is pointless to separate the Mississippi from its tributaries. The upper Mississippi River, as the river above St. Louis is known, rises near the Canadian border at Lake Itasca in Minnesota. That stream has pride of name, of course, but the Missouri, which begins some nine thousand feet above sea level in the Rocky Mountains of Montana and joins the upper Mississippi at St. Louis, is a far longer river. The Arkansas River, which rises near Leadville, Colorado, and joins the Lower Mississippi halfway between Memphis and Vicksburg, is also longer than the Upper Mississippi. So is the Red River of the South, which rises in the Texas Panhandle. The relatively short Ohio, meanwhile, which rises in western Pennsylvania and Virginia and joins the Upper Mississippi at Cairo, Illinois, to form the Lower Mississippi, brings more water to the party than any two other tributaries combined. The truth is that any moving water south of the Great Lakes and between the Appalachians and the Rockieswith the exception of a few relative tricklesis going to Louisiana. The Mississippi, the Mississippi watershed, the Mississippi basin, the Mississippi catchment41 percent of the continental United Statesits all one river.

Parts of the river are older than the Atlantic Ocean. Parts of it were created yesterday. The Mississippi and its tributaries were the routes by which the first humans explored North America, and the earliest evidence (for the time being) of human habitation of the continent is in a rock shelter overlooking a small tributary of the Ohio in Pennsylvania. Agriculture developed independently in the Mississippi River basin, and with it, surplus food for artists, warmongers, shamans, and potentates. For millennia, cultures rose and fell in the watershed, often leaving behind elaborate earthworks and exquisite artifacts but just as often disappearing without leaving much behind. Eventually the greatest pre-Columbian city in North America was built beside the Mississippi River at Cahokia, in Illinois.

The corpse of the first European known to have explored the interior of North AmericaHernando de Sotowas sunk in the Mississippi River nearly five hundred years ago. Two hundred years later George Washington got his first taste of battle during an engagement in the watershed over whether Britain or France would control the river. That skirmish started the Seven Years War, the first global war, which Americans know as the French and Indian War.

In many ways, the story of the Mississippi basin since the end of the French and Indian War is also the story of the federal government of the United States. The taxes that American tea-partiers revolted against were levied to pay for Britains wars in the watershed. King Georges attempts to control the pace of settlement across the Alleghenies was one of the intolerable acts of 1774 later cited in the Declaration of Independence.

After the American Revolution, the one tangible asset the national government owned was the land west of the Appalachians. The first war fought by the newly independent United States was therefore to convince the resident Indians of that new political and military reality. The first road financed by the federal government of the United States was built to get to the watershed; the first civil works built by the Army Corps of Engineers was to improve navigation in the watershed; the first scientific publication by the Smithsonian Institution was a study of the archaeology of the watershed; the first request for federal disaster relief came from Missouri, after the New Madrid earthquakes on the Mississippi River in 1811; the first efforts by the national government to impose safety regulations on a private industry were the steamboat acts of 1838 and 1852.