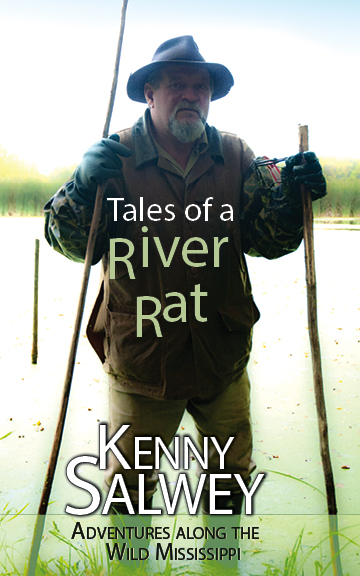

Adventures along the

Wild Mississippi

Kenny

Salwey

Text 2005, 2012 Kenny Salwey

Photographs Andrew Graham-Brown: iii, vi, xxiv, 200, 202; Mary Kay Salwey: viii, xiv, xx; Robert Drieslin: lii

Illustrations courtesy of the US Fish and Wildlife Service: Bob Savannah: 1, 24, 32, 42, 100, 108, 128; Bob Hines: 86, 174; Tom Kelley: 124, 146, 152 (bottom), 176

Illustrations courtesy of the Canadian Museum of Nature: Charles Douglas: 2, 30, 60, 72, 90, 152 (top), 180

Illustration Teeda LoCodo: 188

First published by Voyageur Press, 2005

Published by Fulcrum Publishing, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval systemexcept by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a reviewwithout permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Salwey, Kenny, 1943

Tales of a river rat : adventures along the wild Mississippi / Kenny Salwey.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-55591-763-0 (pbk.)

1. Salwey, Kenny, 1943- 2. Naturalists--Wisconsin--Biography. 3. Floodplain forest ecology--Mississippi River Watershed. 4. River life--Mississippi River Watershed. 5. Country life--Mississippi River Watershed. 6. Mississippi River Watershed--Social life and customs. I. Title.

QH31.S16A3 2012

577.30974--dc23

2012019924

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Design by Jack Lenzo

Fulcrum Publishing

4690 Table Mountain Dr., Ste. 100

Golden, CO 80403

800-992-2908 303-277-1623

www.fulcrumbooks.com

This book is dedicated to my parents,

Willard and Melvina Salwey. Both were

born hill-country folk close to the river

where they have lived well over ninety years.

They allowed me at a very early age

to learn about and to love Nature.

Over the past sixty-two years, I have

thought of them in a two-word phrase:

Pappa and Momma, Pa and Ma, Mom

and Dad, Mother and Father. However,

wonderful parents says it best.

Foreword

Andrew Graham-Brown

Andrew Graham-Brown is an independent producer and director specializing in wilderness filmmaking. He spent two years with Kenny Salwey in the Upper Mississippi River valley creating the wildlife documentary Mississippi: Tales of the Last River Rat . Commissioned by the BBC and the Discovery Channel and produced through Graham-Browns production company @GB Films, the film won a Best Television Program award, as well as merit awards for conservation message and editing, at the 2005 Missoula International Wildlife Film Festival. Graham-Brown lives in Bristol, England.

My fortune is my memory of distant people and far-off lands. As a filmmaker, Ive ridden wild horses in Outer Mongolia and tracked black rhinos on the African plains with the San Bushmenthe oldest, and to my mind, most naturally resourceful people on earth. Recently, I ran away from the diabolical bloodcurdling intentions of a charging Komodo dragonfunny now, but not then. Once upon a time, I experienced firsthand the primeval joy of making fire the ancient waytwo sticks rubbed together to make a sparkwith the aboriginal people of Australias Northern Territory. But the story I most like to brag about down the pub is the time I was in the core of the Big Apple. Out of the blue, I got a call from the BBC in England: Andrew, would you mind interviewing Keith Richards tomorrow afternoon, roundabout teatime, at his home in Connecticut, New England? I was on a roll. Here was a case of being in the right place at the right time. The sliding doors opened, I stepped into the masters drawing room, and a living legend sung me the blues.

Today, Ive got the blues. Im sitting here at home in England on a depressingly drizzly day that so typifies my hometown of Bristol in March. I could let my mood be dampened, but instead I elevate my spirits by reflecting on my proudest and most treasured filmmaking experience: two years spent traveling the backwaters of the Upper Mississippi River with a man Ive come to call my father.

My real dad lives in the Cotswolds, quintessential picture-postcard England. Along with my beloved mother, he nurtures a most beautiful garden. The organically toiled soil burgeons with life even in the dead of winter. My dad first met Kenny on the veg patch among the brussels sprouts in autumn. I know from their talk back and forth that my old man approves of me appropriating his title to speak of my sagelike friend, Kenny Salweya man renowned the world over for his poetic prose and elegantly simple philosophy of Nature.

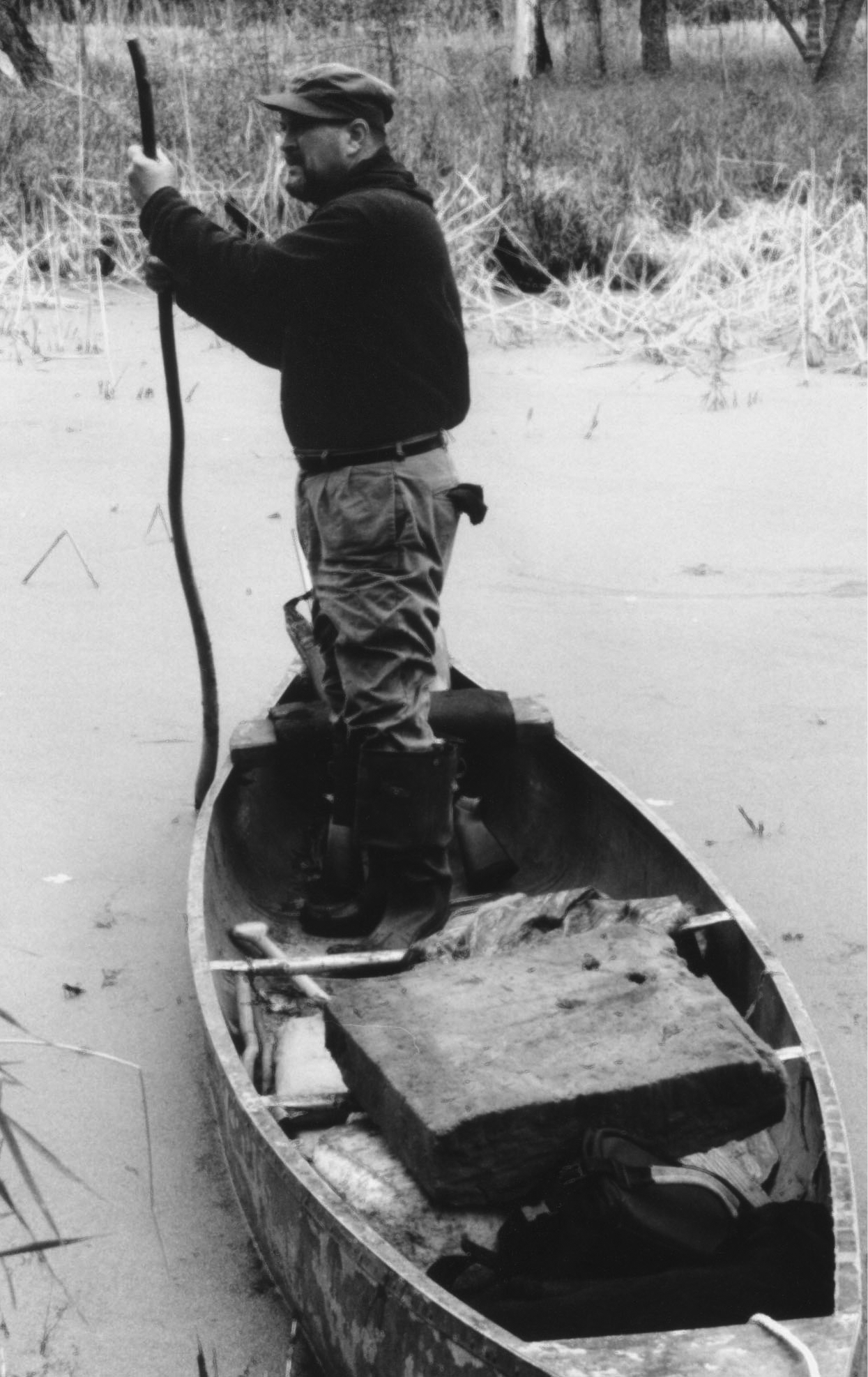

Through my eyes, the Mississippi and Kenny Salwey are one and the same. He is my first and last impression of the big river. Weve walked and talked sense and nonsense on winters thick mantle of ice; dug the pungent skunk cabbage root during the verdant joy of spring; wiled away the dog days of summer near cool streams, fishing for elusive brook trout; and weve sat together, content in silence, marveling at the outstanding colors of fall.

Once on a fine summers day, I sat in Kennys canoe gabbling in a rather loud voice about nothing in particular, and Kenny paused on his oar to say, A June morning wouldnt be complete without the sound of birdsong. The birds all sing in a different key, they sing a different song, and they all sing at the same time. It makes a beautiful lullaby. It is salve to the soul. Yet, if us humans were to try and do that, we couldnt stand it in the same room.

Life is too short to hurry through it, the old sage once told me during a lunch break on the riverbank. Hed seen me wolfing down his delightful ninety-two-year-old mothers delicious homemade apple pie. I was chomping at the bit, urging Kenny to break out of his lazy old-man-river routine and get his proverbial arse in gear. I thought of ditching his oars for a 100-horsepower engine, a petroleum-driven technology that could propel our canoe to the next location in time for magic hourthe fleeting moments of light at days end that wildlife filmmakers crave to record to craft their version of exquisite Nature. As I paddled the swift and steady current downstream, I thought about Kennys wise words, ditched my watch, and took time to slow down and take pleasure in the natural world all around. I began to hear and see the gorgeous, integrally linked details bound together in the ancient rhythms of what Kenny calls the Circle of Life. The gurgling waters of the Mississippi that keep on going round and round, the whisper of cottonwood leaves, and the hover dance of dragonflies above the waters surface. Life is too short to hurry through it . It is a simple yet profound statement, and Kenny reminded me during our times exploring the beauty of the seasons that there is greatness in simplicity.

We first met at Big Lake Shack, known to some as the lair of the last Mississippi river rat. It stands a canoe-length square, a stones throw from the waters edge. On the black tarstained oak door, a bright yellow sign reads La Maison de Salweyin homage, I later learn, to his French Canadian roots. Our shaking of tentative hands was a bit like two inquisitive dogs meeting in the park for the first time. The city boy, armed head to toe with every conceivable survival gadget and gizmo known to modern man, meets swamp hermit, who some fools might reckon has spent too many years in the woods, holed up in a log cabin he built with his own hands and sweat. Kenny raised what we in England call a very hairy eyebrow and said many words in his singular utterance: Uh-huh. All the same, the old man of the woods reassured me with a full-toothed smile, and he graciously ushered me over the threshold of his shack into a world where I will always feel at home. It reminds me of my grandfathers potting shed, at the end of his flower garden in an old part of England called the New Forest. The beguiling interior, chockablock with the paraphernalia and memorabilia of a life spent subsisting in the wild, says so much about the man. Where my grandfather hung dried flowers, Kenny hangs fishing lures, snapping turtle shells, and raccoon tails. Grandpa used a nonalphabetical filing cabinet of Clan tobacco tins to stash mementoes and letters from his harrowing teenage years in the trenches of World War I. Kenny, on the other hand, employs a trusty old Copenhagen snuff tin to store grubs he harvested from the galls of last years goldenrod prairie plantNatures gift of bait to catch sunfish and crappies.