THE LAST RIVER RAT

Kenny Salweys Life in the Wild

By J. Scott Bestul & Kenny Salwey

With Pen-and-Ink Illustrations by Mary Kay Salwey

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MANY THANKS TO my friend and budding river rat, J. Scott Bestul. This book was his idea. From the start we hit it off, and Im grateful for his expertise and his passion for the land.

I would like to thank Reggie McCloud and all the folks at Big River Newsletter for allowing me to create five years worth of monthly almanacs for themexcerpts of which appear in this book.

Also a big thank-you to my editor, Michael Dregni, and the staff at Voyageur Press.

Lastly, I want to thank the reader for taking more than a passing interest in nature. During the time it takes you to read this book, we will be fellow travelers in the great Circle of Life. There is no greater gift than the sharing of ones time with another. The critters and I say thank you from the bottom of our hearts.Kenny Salwey

ID LIKE TO thank Michael Dregni for his unflagging support during this project, and Mary Kay Salwey for her wonderful drawings and honest input. To the thousands of folks who, through volunteer or professional effort, keep the Upper Mississippi River one of the worlds natural wonders, a heartfelt appreciation. But my deepest gratitude goes to Kenny, who showed me a beautiful place and a way of looking at things that I hope Ill never lose.J. Scott Bestul

DEDICATION

I DEDICATE THIS book to all the river rats who have gone before me, from the ancient people who first saw the Great River to those of just yesterday. I follow them all in the wake of their canoes.

Most of all I dedicate this book to my beloved wife, Mary Kay, who sorted through my longhand scribblings and painstakingly drew the remarkable illustrations for this book. She is the light and the love of my life. She kept me on task and gave me the motivation to complete the book.Kenny Salwey

FOR SHARI, WHO reads every word before they escape our house. J. Scott Bestul

CONTENTS

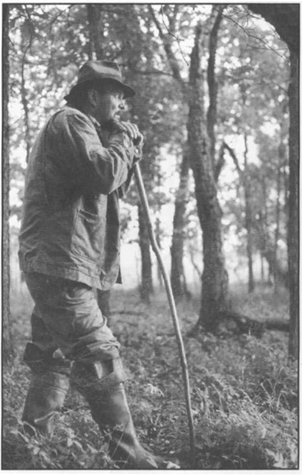

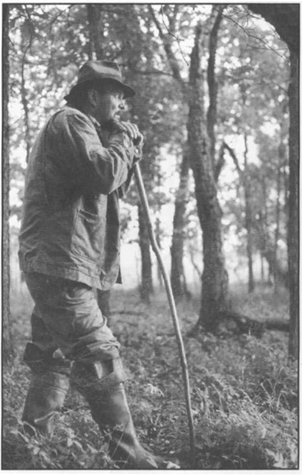

Leaning on his walking stick, Kenny pauses to watch the woods. (Photograph Mary Kay Salwey)

INTRODUCTION

Of River Rats and the Big River

Along the Mississippi River, old-timers often speak with reverence of a fabled fraternity of men and women who not only know the Big River, but have made it part of their lives and counted on it for a livelihood. Riverfolk have a name for this dwindling clan: They are known as river rats. While the name conjures images of a sodden, bedraggled critter living in a mud house, its considered quite a compliment around these parts, and unlike most names, its one thats earned, not given at birth. Wresting a living, or even part of one, from the river is hard business. As locals are quick to point out, there are no dumb river rats who are very old; the Mississippi does a tidy job of weeding out those who make mistakes at the wrong times.

River rats are a respected bunch, and until a generation or two ago, they were fairly common. Every rivertown claimed a handfuland in some cases entire familieswho looked to one of the worlds greatest rivers for sustenance, income, and recreation. In the summer there were fish to catch and clams to dig. Come fall, ducks and deer provided meat for the smokehouse and dollars for the wallet, as there were always out-of-towners willing to hire a guide for a day. As fall gave way to winter, traps were set for beaver and mink, muskrat and otter, all of whose furs would bring the money needed to make it through until spring. And when the snow and ice left the river, the cycle began again. Theirs was a life lived close to the water.

Today, river rats are few and far between. Unspoiled stretches of the Big River are hard to find, and its not a lifestyle that will earn you the keys to a fancy house or a big car. Living off the river is a dying way of life.

This is not true everywhere, however. Along the banks of the Mississippi where the waters separate Minnesota from Wisconsin, people speak still of a legendary modern-day river rat, the last river rat. This man is Kenny Salwey.

Kenny grew up on a small farm near Cochrane, Wisconsin, at a time when the river rats way of life was still attractive. As a prospective river rat, he had no shortage of role models. Although he already spent his days outdoors doing farm chores, he longed to learn more of the natural worldof the plants and creatures living in the hills surrounding the river, and of the fish and turtles and ducks that called the backwaters home. Farm life was better than town life, but it was also tedious. Kenny wanted to live according to natures rhythms, to let the seasons dictate the work that needed to be done. River rats seemed to have captured that essence perfectlycalling no person boss and relying only on their resourcefulness, ingenuity, and knowledge of the country to survive. He could think of no better life.

Kenny had rudimentary training from family members, whose French-Canadian roots remained strong. I was taught young how to gather mushrooms, dig ginseng, setline for catfish, hunt ducks, Kenny recalls. Those activities were part of my heritage. Not all of my family worried about gainful employment, and many of our activities were driven by the rhythms of the seasons. When certain times of the year came, there were important things to do for our survival, and these were the things I loved, even as a young boy.

Of course, acquiring enough knowledge to be a river rat was not accomplished overnight, and most river folk guarded their secrets jealously. I hung around whatever river people would let me, listening closely to what they said and watching what they did, Kenny says. I learned a lot that wayfrom the old ones. But they werent willing to share everything. Each knew different places: favorite fishing holes, the best creek bank to trap a mink, the wild celery beds where the ducks came each fall. You could pick up a little bit from each person you knew, but most things you still needed to learn on your own.

Kenny made his home in the Whitman Swamp, a 6,000-acre swampland south of Buffalo City, Wisconsin, that is shut off from the modern world in the Big Rivers backwaters. And, in over four decades of roaming the Whitman, he has come to know the swamp almost as intimately as any of natures creatures who live there.

The Whitman Swamp was separated from the main channel of the Upper Mississippi River by a dike built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1933. The dike consisted of five miles of earth and rock beginning just downstream of Buffalo City, and was part of the vast complex of dams, locks, and levees meant to channel the Mississippis power; the system was engineered to protect rivertowns from flooding and make commercial navigation safer and more successful. That was the dikes expressed purpose, anyway.

What the Whitman Dike actually did was shut the swamp off from the modern world. On the river side of the dike, tugs push barges full of grain and coal between New Orleans and Minneapolis-St. Paul, pleasure boaters steer yachts and sailboats up and down the channel, campers pitch tents on sand-mountains of dredge spoil, and jet skiers steer whining machines into their own chop. From ice-out until autumns end, the main channel seems little more than a water-filled freeway carrying a mix of riders: businesspeople, commuters, sightseers, and Sunday drivers.