JOHN GRAVES

John Graves was born in Texas and educated at Rice and Columbia universities. He has published a number of books, chiefly nonfiction concerned with his home region. He lives with his wife on some four hundred acres of rough Texas hill country, which he described in his book Hard Scrabble.

ALSO BY JOHN GRAVES

The Water Hustlers (with T.H. Watkins and Robert Boyle)

Hard Scrabble

The Last Running

From a Limestone Ledge

Blue and Some Other Dogs

Self-Portrait, with Birds

A John Graves Reader

John Graves and the Making of Goodbye to a River

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, JULY 2002

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, JULY 2002

Copyright 1959 by The Curtis Publishing Company

Copyright 1960, copyright renewed 1988 by John Graves

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1960.

Certain passages in this book first appeared in Holiday in somewhat different form.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Departures and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Graves, John, 1920

Goodbye to a river, a narrative / John Graves. [ist ed.]

p. cm.

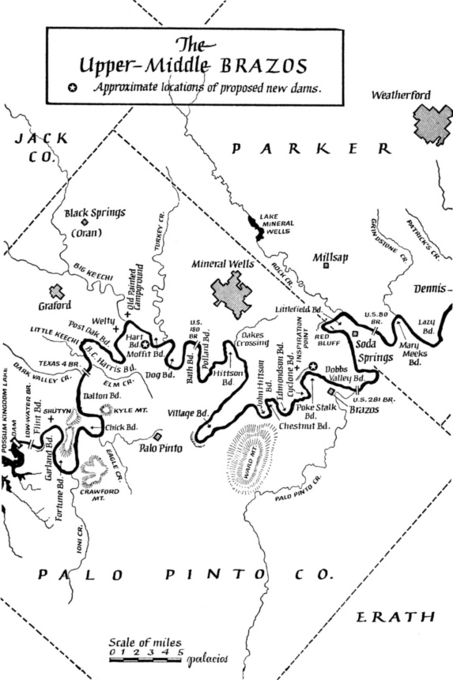

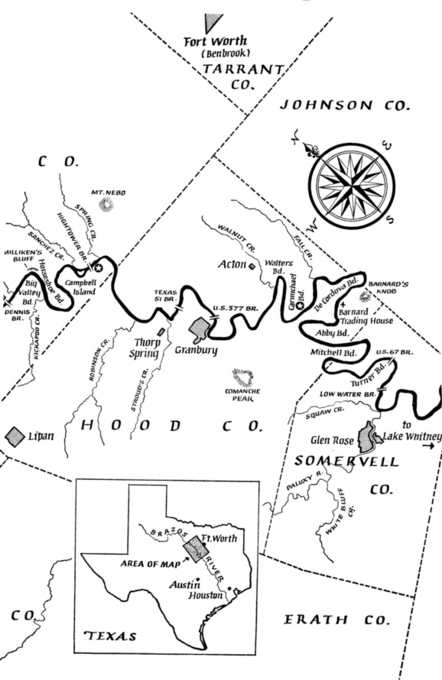

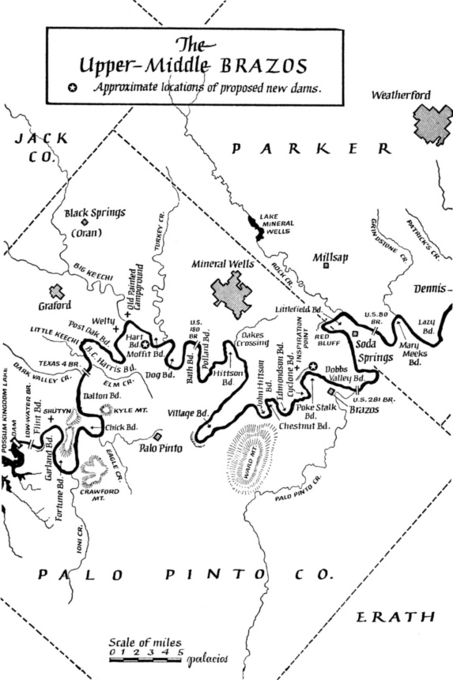

Brazos River (Tex.) 2. Brazos River Valley (Tex.) I. Title.

F392.B842 G7

917.641 60-10954

eISBN: 978-0-307-77335-7

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1_r1

for H.,

who came along at about the same time.

I hope the world she will know

will still have a few rivers and

other quiet things in it.

A NOTE

T HOUGH this is not a book of fiction, it has some fictionalizing in it. Its facts are factual and the things it says happened did happen. But I have not scrupled to dramatize historical matter and thereby to shape its emphases as I see them, or occasionally to change living names and transpose existing places and garble contemporary incidents. Some of the characters, including at times the one I call myself, are composite. People are people, and if you put some of them down the way they are, they likely wouldnt be happy. I dont blame them. Nevertheless, even those parts are true in a fictional sense. As true as I could make them.

CONTENTS

PART ONE

By heaven! cried my father, springing out of his chair, as he swore,I have not one appointment belonging to me, which I set so much store by, as I do by these jack-boots,they were our great-grandfathers, brother Toby,they were hereditary.

By heaven! cried my father, springing out of his chair, as he swore,I have not one appointment belonging to me, which I set so much store by, as I do by these jack-boots,they were our great-grandfathers, brother Toby,they were hereditary.

CHAPTER ONE

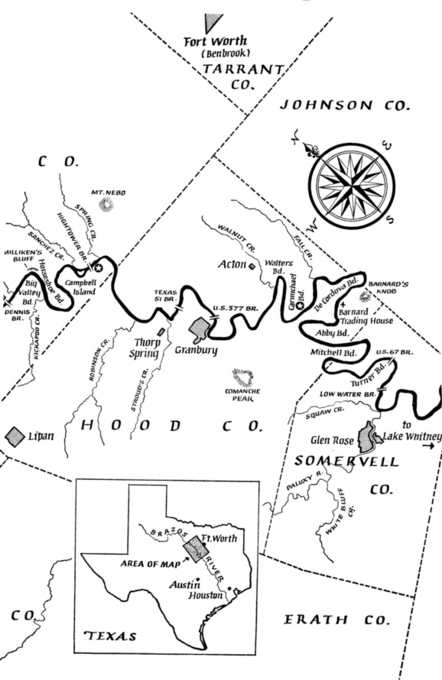

USUALLY, fall is the good time to go to the Brazos, and when you can choose, October is the best monthif, for that matter, you choose to go there at all, and most people dont. Snakes and mosquitoes and ticks are torpid then, maybe gone if frosts have come early, nights are cool and days blue and yellow and soft of air, and in the spread abundance of even a Texas autumn the shooting and the fishing overlap and are both likely to be good. Scores of kinds of birds, huntable or pleasant to see, pause there in their migrations before the later, bitterer northers push many of them farther south. Men and women are scarce.

Most autumns, the water is low from the long dry summer, and you have to get out from time to time and wade, leading or dragging your boat through trickling shallows from one pool to the long channel-twisted pool below, hanging up occasionally on shuddering bars of quicksand, making six or eight miles in a days lazy work, but if you go to the river at all, you tend not to mind. You are not in a hurry there; you learned long since not to be.

October is the good month.

I dont mean the whole Brazos, but a piece of it that has had meaning for me during a good part of my life in the way that pieces of rivers can have meaning. You can comprehend a piece of river. A whole river that is really a river is much to comprehend unless it is the Mississippi or the Danube or the Yangtze-Kiang and you spend a lifetime in its navigation; and even then what you comprehend, probably, are channels and topography and perhaps the honky-tonks in the rivers towns. A whole river is mountain country and hill country and flat country and swamp and delta country, is rock bottom and sand bottom and weed bottom and mud bottom, is blue, green, red, clear, brown, wide, narrow, fast, slow, clean, and filthy water, is all the kinds of trees and grasses and all the breeds of animals and birds and men that pertain and have ever pertained to its changing shores, is a thousand differing and not compatible things in-between that point where enough of the highland drainlets have trickled together to form it, and that wide, flat, probably desolate place where it discharges itself into the salt of the sea.

It is also an entity, one of the real wholes, but to feel the whole is hard because to know it is harder still. Feelings without knowledgelove, and hatred, tooseem to flow easily in any time, but they never worked well for me.

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, JULY 2002

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, JULY 2002

By heaven! cried my father, springing out of his chair, as he swore,I have not one appointment belonging to me, which I set so much store by, as I do by these jack-boots,they were our great-grandfathers, brother Toby,they were hereditary.

By heaven! cried my father, springing out of his chair, as he swore,I have not one appointment belonging to me, which I set so much store by, as I do by these jack-boots,they were our great-grandfathers, brother Toby,they were hereditary.