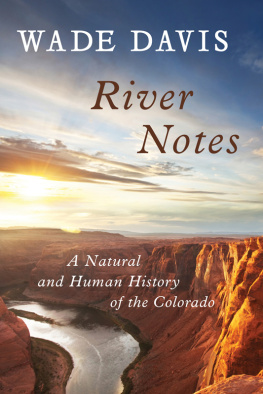

River Notes

A Natural and Human History of the Colorado

Wade Davis

Washington | Covelo | London

Copyright 2013 Wade Davis

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, Suite 300, 1718 Connecticut Ave., NW, Washington, DC 20009

ISLAND PRESS is a trademark of the Center for Resource Economics.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Davis, Wade.

River notes : a natural and human history of the Colorado / Wade Davis.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-61091-361-4 (hardback) ISBN 1-61091-361-2 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61091-020-0 (paper) 1. River engineeringColorado River Watershed (Colo.-Mexico)History. 2. Colorado River Region (Colo.- Mexico)Environmental conditions. 3. Colorado River (Colo.-Mexico)Description and travel. I. Title.

TC425.C6D35 2012

557.913dc23

2012020613

Printed on recycled, acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Keywords: Island Press, the Colorado River, the Grand Canyon, water, water conservation, Lake Powell, the Southwest, natural history

Man always kills the things he loves, and so we the pioneers, have killed our wilderness. Some say we had to. Be that as it may. I am glad I shall never be young without wild country to be young in. Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map?

Aldo Leopold,

A Sand County Almanac, 1949

In 1922, having completed work on the first comprehensive management plan for the Grand Canyon, Aldo Leopold, along with his younger brother, set out by canoe to explore the mouth of the mighty Colorado. At the time the main flow of the Colorado reached the sea, carrying with it each year millions of tons of silt and sand and so much fresh water that the rivers influence extended some forty miles into the Gulf of California. The alluvial fan of the delta spread across two million acres, well over three thousand square miles, a vast riparian and tidal wetland the size of the state of Rhode Island. It was one of the largest desert estuaries on earth. Off shore, nutrients brought down by the river supported an astonishingly rich fishery for bagre and corvina, dolphins, and the rare and elusive vaquita porpoise, the worlds smallest marine cetacean. At the top of the food chain was the totoaba, an enormous relative of the white sea bass that grew to three hundred pounds, spawned in the brackish waters of the estuary and swarmed in the Sea of Cortez in such abundance that even fishermen blinded in old age, it was said, had no difficulty striking home their harpoons.

In contrast to the searing sands of the Sonoran Desert through which the lower Colorado flowed, and the blue and barren hills of the Sierra de los Cucaps, cradling the river valley to the north and west, the delta was lush and fertile, a milk and honey wilderness, as Leopold called it, of marshes and emerald ponds with cattails and wild grasses yielding to the wind, and cottonwoods, willows, and mesquite trees overhanging channels where the water ran everywhere and nowhere, as if incapable of settling upon a route to the sea. The river, wrote Leopold, could not decide which of a hundred green lagoons offered the most pleasant and least speedy path to the gulf. So he travelled them all, and so did we. He divided and rejoined, he twisted and turned, he meandered in awesome jungles, he all but ran in circles, he dallied with lovely groves, he got lost and was glad of it, and so were we.

Drifting with the ebb and flow of the tides, waking by dawn to the whistles of quail roosting in the branches of mesquite trees, making camp on mudflats etched with the tracks of wild boar, yellowlegs, and jaguar, the Leopold brothers experienced the Colorado delta much as had the Spanish explorer Hernando de Alarcn, who first reached its shores in 1540. There were bobcats draped over cottonwood snags. Deer, raccoons, beavers, and coyotes, and flocks of birds so abundant they darkened the sky. Avocets and willets, mallards, widgeons, and teals, scores of cormorants, screaming gulls, and so many egrets on the wing that Leopold compared them in flight to a premature snowstorm. He wrote of great phalanxes of geese sideslipping toward the earth, falling like autumn leaves. On every shore he saw clapper rails and sandhill cranes, and overhead, doves and raptors scraping the sky.

It was an exquisite landscape, rich in fauna and flora, with hundreds of species of birds and rare fish, and along the mudflats, melons and wild grasses that yielded great handfuls of edible fruits and seeds. But the brothers sojourn in the delta was not without its challenges. The river was too muddy to drink, the lagoons too brackish, and every night they had to dig to find potable water. The dense and impenetrable thickets of cachinilla made movement on land almost impossible, leaving Leopold doubtful that people had ever lived in the wetlands. The Delta having no place names, he wrote, we had to devise our own as we went.

In this Leopold was quite wrong, for the marshes and lagoons of the Colorado delta had for a thousand years been home to the Cocopah Indians, who viewed themselves as the offspring of mythical gods, twins who had emerged from beneath the primordial water to create the firmament, the earth, and every living creature. In 1540 Hernando de Alarcn encountered at the mouth of the river not hundreds but thousands of men and women, who, in their rituals, he reported, revealed a deep reverence for the sun. He described the Cocopah as tall and strong, with bodies and faces adorned in paint. The men wore loincloths, the women coverings of feathers that fell back and front from the waist. Every adult man had shell ornaments hanging from the nose and ears, and deer bones suspended from bands of cordage wrapped around the arms. They gathered in great numbers, small bands of a hundred, larger assemblies of a thousand, and in one instance, as Alarcn reported, no fewer than six thousand.

To support such populations, the Cocopah grew watermelons and pumpkins, corn, beans, and squash. From the wild they feasted on fish, wood rats, beavers, raccoons, feral dogs, and cattail pollen and tule roots. In the first months of the year, with their stores of harvested food exhausted, they travelled to the high desert to gather cactus and agave. Mesquite pods, ground with a metate, yielded flour that was made into cakes or mixed with water and consumed as a drink. Their dwellings were simple structuresround domes of reeds and brush. They slept beneath blankets of rabbit skins. They moved through the marshes in dugout canoes, carved from cottonwood, or on rafts of logs bound together by ropes made from willow bark or wild grasses.

Their most elaborate rituals occurred at death. The body of the deceased was fully adorned and then cremated, along with all possessions and memories. Shelters were burned and even footprints eradicated to ensure that the spirits of the dead abandoned all attachments and were never tempted to return to the realm of the living. The destiny of the dead was a land of plenty, not far from homesalt flats near the mouth of the river. At the funeral ceremony, the orator shaman recalled all the events in the life of the departed, as the relatives danced, moving four times around the burning pyre, wailing, sobbing, and singing the songs of death. With the body nearly consumed, the women of the family turned their backs to the flames and solemnly cut off their hair as a sign of mourning. Then, with the healing smoke of tobacco and the relief of a ritual bath, each severed all connection to the deceased, even as wood in massive amounts was added to the fire to create a light that would shine through the night and illuminate in every corner of the delta the pathways of the living.

Next page