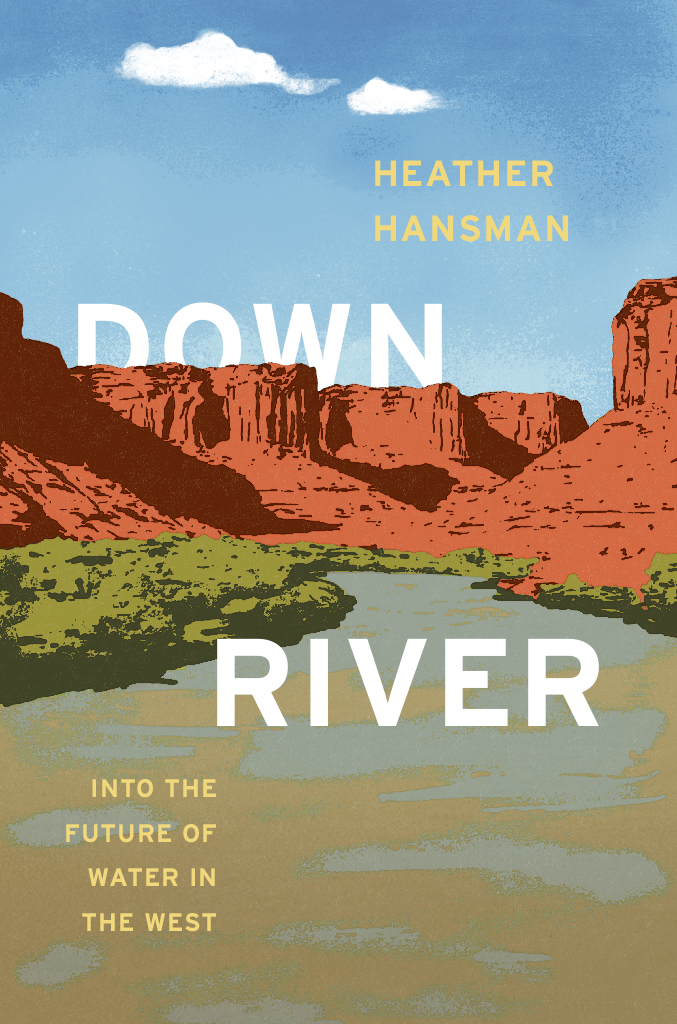

DOWNRIVER

DOWN RIVER

Into the Future of Water in the West

Heather Hansman

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2019 by Heather Hansman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-43267-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-43270-0 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226432700.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hansman, Heather, author.

Title: Downriver : into the future of water in the West / Heather Hansman.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2019. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018031113 | ISBN 9780226432670 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226432700 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Water conservationWest (U.S.) | Water-supplyWest (U.S.)

Classification: LCC TD388.5 .H357 2019 | DDC 333.9100978dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018031113

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Each time we say the River we seem to resurrect the lost wild country.

Ellen Meloy, Ravens Exile

CONTENTS

702 CFS

686 CFS

2,790 CFS

6,940 CFS

9,080 CFS

9,180 CFS

10,600 CFS

6,820 CFS

3,220 CFS

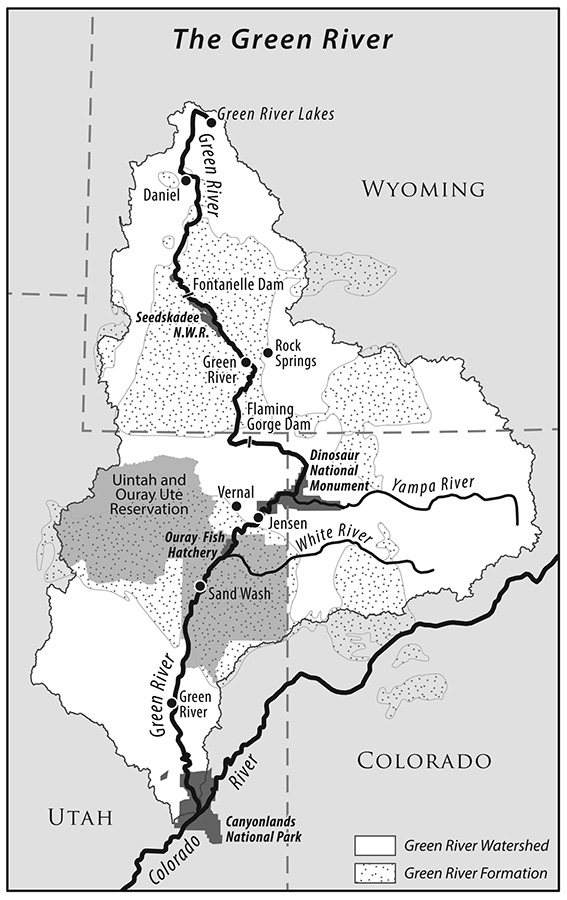

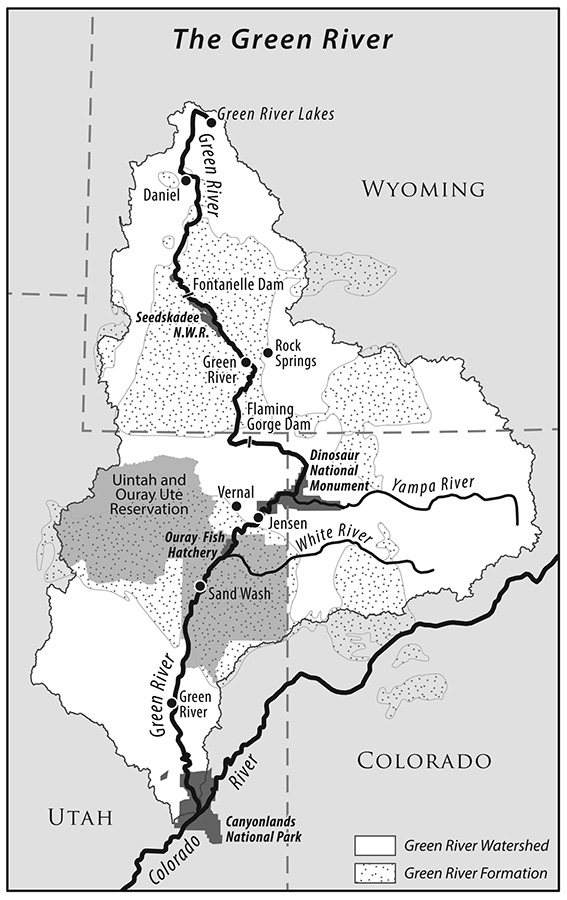

The Green River Basin. (Map created by Nicole Grohoski.)

702 CFS

Before lunch we hit the first real rapid, Moose Creek, a narrow, jagged rock sluice that had looked fast and pinchy when wed driven past it the night before, peering into the gorge from the road. Now, with skimpy early-season flows, theres barely enough water to split the guts of the glacially eroded granite. A few fly-fishermen flick their lines into the pools above it as we pull into an eddy upstream of them to scout the rapid, looking downriver into the gnash of whitewater. The river pillows up, then drops over a horizon line. We cant see beyond, but it looks like theres enough water to sneak our tubby little pack rafts through. Mike decides to walk around. Ben and I slide back into our boats and paddle out into center channel.

The current swells as I tee up to the top wave, pointing my bow into the break. I had been nervous, sure that Id been off the water for too long, uncomfortable in a new boat, uncertain how my body would hold up, or whether it was stupid and stubborn to try to take a trip this long. My paddle clashes with a rock, shaking me off my line, and then Im in the trough of the wave train, fighting to stay upright. Theres a specific joy in reading water, and in knowing the micro adjustments necessary to find a tongue of fast current and thread through the shallow, ribby rapids, and my muscle memory comes back in the quick twitch of whitewater. I run through clean. Its over in a flurry of frantic paddle strokes and a smack of just-melted glacier to the face. Ben cleans it, too, and catches up to me in the slack water below the rapid. We tamp down our nervous laughs, catch our breath, turn and point our boats downstream.

Its crucial, its overused, and its at risk. There are deeply divisive battles over the water were currently floating. The Green starts here, in the glaciated high alpine of Wyomings Wind River Range, then winds through hundreds of miles of sagebrush flats, scrubby plains, tight gorges, and empty gas lands to the red rock desert of Utahs Canyonlands National Park, where it meets up with the main stem of the Colorado.

Because the landscape between here and there is remote and rugged, the Green and its tributaries have been touched far less than most other rivers in the West, which are overtapped thanks to human population growth and decades-long drought. Its one of the only parts of the river system with significant water left to squeeze out. But all the signs of western developmentfrom coal to cattle to citiesare here. And as population swells in cities like Denver and Salt Lake, and as climate change shrinks stream flow, the question of how the water in this river is used and how far it can be stretched is becoming more urgent.

Its a question of whether our current way of living is sustainable in a drier, increasingly crowded West, and how it will have to change if it isnt. The Green is at the heart of that question, and I want to know what the answers might be. Im here, white-knuckling my paddle in a stretch of water Ive never seen before, because I decided the best way to understand it was the best way I know to understand a lot of thingsfrom the river.

We launch cold and early. The suns light cracks the ridge of the Wind River Range, gilding the edges of Square Top Mountain and glancing down onto the Green River Lakes. Mike, my journalism school roommate, and his coworker Ben, who have come along for a few days, make breakfast. We pound coffee and eat a couple of sausages each, then slide our pack rafts into the chill water on the lip of the lowest lakes beach. A Wyoming Fish and Game warden in a red shirt and a white truck, with a black dog loping alongside him, stops us on the shore. How far you going? he asks, as we settle into our boats and shake blood into our fingers. I swell up a little, sit taller and say, All the way. If he notices my attempt at bragging, he ignores it, and he waves us off as we paddle along the edge of the gravelly shore. Its May, and the snow is just starting to run off the peaks that ring the basin, swelling the river. I can see the glitter of rocks on the bottom through the crystalline, sediment-free water. We make our way toward the end of the lake, and the pooled-up water starts to pick up speed. Moving slowly, but moving. Are we on the river yet? Do you think were on the river yet? Ben keeps asking as we curve along the bank. We paddle under a spindly footbridge that crosses at the narrowest point. I can see the current pillowing up on the bridge pilings as it moves slowly downstream, and all of a sudden, I think we are.

I am going all the way. The boys are on board for the beginninga weekend on the water before they have to go back to their jobs at the newspaper in nearby Jackson Holebut I have 730 miles and a season to paddle the Green from here, in the headwaters, to its confluence with the Colorado. Im a paddler, this river is important to me, but I feel confused about the future of water. I want to understand the complicated ways in which its water is used and where the conflicts lie in a system that needs to change to accommodate more people and less water.

The water in the Green, and in the rest of the Colorado River system, is overallocated, and has been since the 1920s, when its estimated flow was divided up between the seven states along the rivers. When the states split up the water, they did so based on incorrect calculations. They allocated more water than actually exists in the rivers, and they did it under the assumption of stationaritythat the amount of water would always be about the same. Were operating at a loss, and using more water than we have, because of embedded, decades-old policies and overstated ambitions. So far, large reservoirs, filled up in wetter times, and unused water rights have prevented the West from running dry, but were creeping toward the bottom of our supply as things get drier and more crowded. It cant last much longer. At some point, the inflow and the amount were using will have to be balanced, and right now no one quite knows how that will work out.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).