THE SOURCE

HOW RIVERS

MADE AMERICA

AND AMERICA

REMADE ITS RIVERS

Martin Doyle

FOR JORDAN, STUART, AND EVELYNMY BOW PADDLERS.

CONTENTS

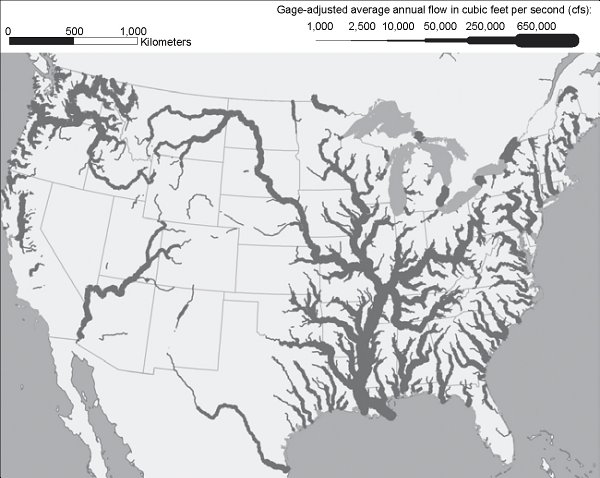

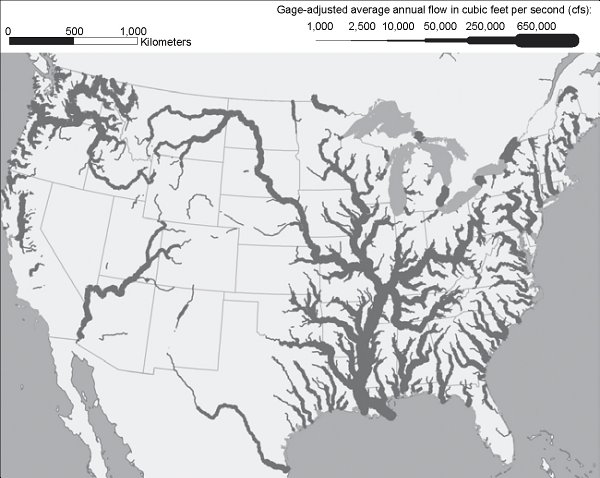

America has more than 250,000 riversover 3 million milesdissecting the fields, cities, and forests of the nation. These arent just any rivers; these are world-class rivers. The Mississippi watershed alone drains the rain and snow that falls on over a million square miles, generating 390 billion gallons of water per day, enough over the course of a year to cover the entire United States with several inches of water. The falling of these rivers over the continents topography generates tremendous power: the Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River is the largest power plant in the United States, yet it makes up only a third of the power production of all the dams just on the Columbia. And Americas rivers span enormous climatological gradients. The Colorado most notably brings runoff from the snow-rich Rockies through thousands of miles of desert, providing the water for nearly 30 million people and more than 1.8 million acres of irrigated land and allowing the production of 15 percent of the nations crops in one of the driest regions on Earth. Anyone in the United States who eats a salad in the winter is enjoying lettuce grown with Colorado River water. Rivers are the defining feature of Americas landscape.

Rivers have shaped the basic facts of America. Most simply, of course, our borders themselves are typically set by riversthe Mississippi, the Ohio, the Red, the Columbia, and the Colorado all form borders between states while the Rio Grande separates the United States from Mexico. Sixteen states were named after rivers, along with over 150 counties.

The rivers of the United States scaled by flow.

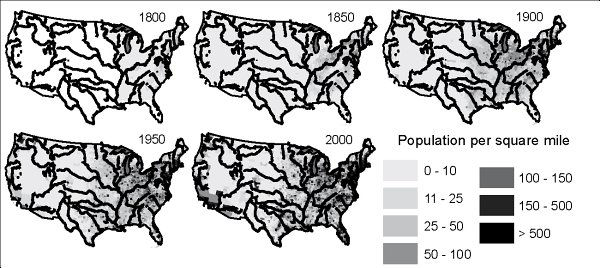

Rivers have also shaped where we live. When European colonists arrived on the Eastern Seaboard of America, they established their farms in the coastal plain, where land was flat and the sluggish rivers, streams, and sloughs were easily plied. As newly arriving settlers moved farther inland, they confronted a geologic peculiarity where the Atlantic coastal plain runs up against the Piedmontthe Fall Line. Upstream of the Fall Line, rivers are entrenched in narrow, steep-walled valleys interspersed with rapids. Downstream are the easily traveled rivers of the coastal plain. At the Fall Line lie rapids or even waterfalls. For anyone trying to move a bale of cotton or a bushel of wheat from the interior by boat, the Fall Line would mark the end of the line where canoes moving downstream would have to be unloaded, portaged, and reloaded. To move goods upstream from the Atlantic, cargo would have to be shifted from larger coastal or ocean vessels to land transportation or smaller canoes or rafts to transport upstream.

All this exchange of goods meant that both goods and money were changing hands: foreign merchants with ships interspersed with country bumpkins and their wagons. In Fall Line ports, entrepreneurs and job seekers alike smelled opportunity. And at the Fall Line ports of the eighteenth century, villages and towns began forming and growing as nascent hubs of commerce, the centers of the emerging market economy. These random places at the intersection of rivers and the Fall Line became natural places for immigrants to settle and cities to grow: Richmond on the James, Washington on the Potomac, Trenton on the Delaware, and nearly all of the other cities peppering the Eastern Seaboard. That the major cities of the eastern United States, and particularly the state capitals, are located at the Fall Line is a simple indicator of how subtle the effect of the physical landscape can be in shaping the demographic landscape.

Cities of the Midwest, the Deep South, and the West are little different. Many cities of Americas interior lie at important river confluences: Pittsburgh where the Monongahela and Allegheny join to form the Ohio, Kansas City at the Missouri and Kansas, and Sacramento at the Sacramento and American rivers. Cities of the Deep South, where rivers are plentiful, are typically situated to avoid wateror at least floods. Memphis, Vicksburg, and Natchez all sit up on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River from a safe elevation yet close enough to be a bustling port for nineteenth-century steamboats or twenty-first-century barge tows. Two of the oldest Mississippi River cities, Saint Louis and New Orleans, likewise sit on slight topographic risesnatural leveesthat have kept their residents above the hydrologic fray for centuries.

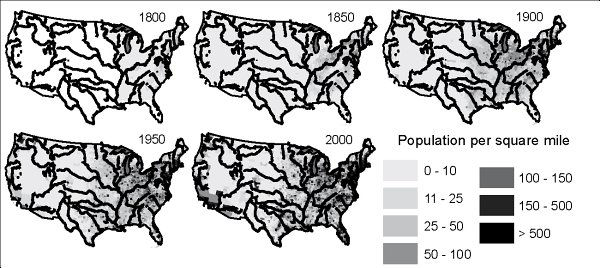

Population density in the United States has traditionally been bounded by and clustered around rivers.

Other centers of Americas riverine society are often less populated but no less formative: they are hubs of energy. Where rivers are constricted to narrow valleys and canyons, or where they cascade over especially powerful waterfalls, their physical power has been harnessed against the rapidly changing backdrop of evolving technology. Settlers of the eighteenth and nineteenth century built their villages around small dams powering waterwheels; twentieth-century engineers and federal agencies built monumental concrete dams and countless turbines to generate power that would be sent through an ever-sprawling electric grid to distant cities and far-flung industries. The power of the Susquehanna River was as essential to grinding colonial grain as the Merrimack River was to spinning the fabric of New England textile mills; the Columbia River was as crucial in extracting aluminum for World War II bombers as the Tennessee River was in refining the uranium those bombers carried. The evolution of technology has allowed rivers to power the rise of America from colonial backwater to industrial juggernaut.

Demographics, technology, and the economyall these aspects of Americas history have played out on a landscape defined by rivers. The simple geologic process of water eroding bits and pieces of sediment has resulted in physical features that have shaped, and continue to shape, the events of modern society.

But rivers have also shaped the very ideas of what America should be. Is a standing, permanent army needed, or might a loose collection of state militia be sufficient? The need for fortifications at the harbors of interstate river ports made a standing army both acceptable and necessary. Which level of government should regulate commerce? River-borne commerce on interstate rivers drove the new republic to have a single national economy rather than a collection of independent state economies. How big should the nation be? The Louisiana Purchasethe acquisition of the entire Missouri River basinchanged the basic geography of America into a vast westward empire. In so doing, it gave enough space for the quintessential frontiersmen and pioneers, along with the idea of manifest destiny. How active should the national government be? Floods of biblical proportion in the early twentieth century, when combined with a nationwide economic depression, forced the nation to accept a far larger role for the federal government than had been tolerated before. Many of the issues in American society have arisen from or been fought over the fact of our riverine republic.

Next page