Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

PROLOGUE

Throw yourself with confidence upon this flowing tide, for upon this generous river shall float navies, richer and more powerful than those of Tarshish... and at its mouth... shall congregate the merchant princes of the earth.

P ERRY M C D ONOUGH C OLLINS, A Voyage Down the Amoor, 1860

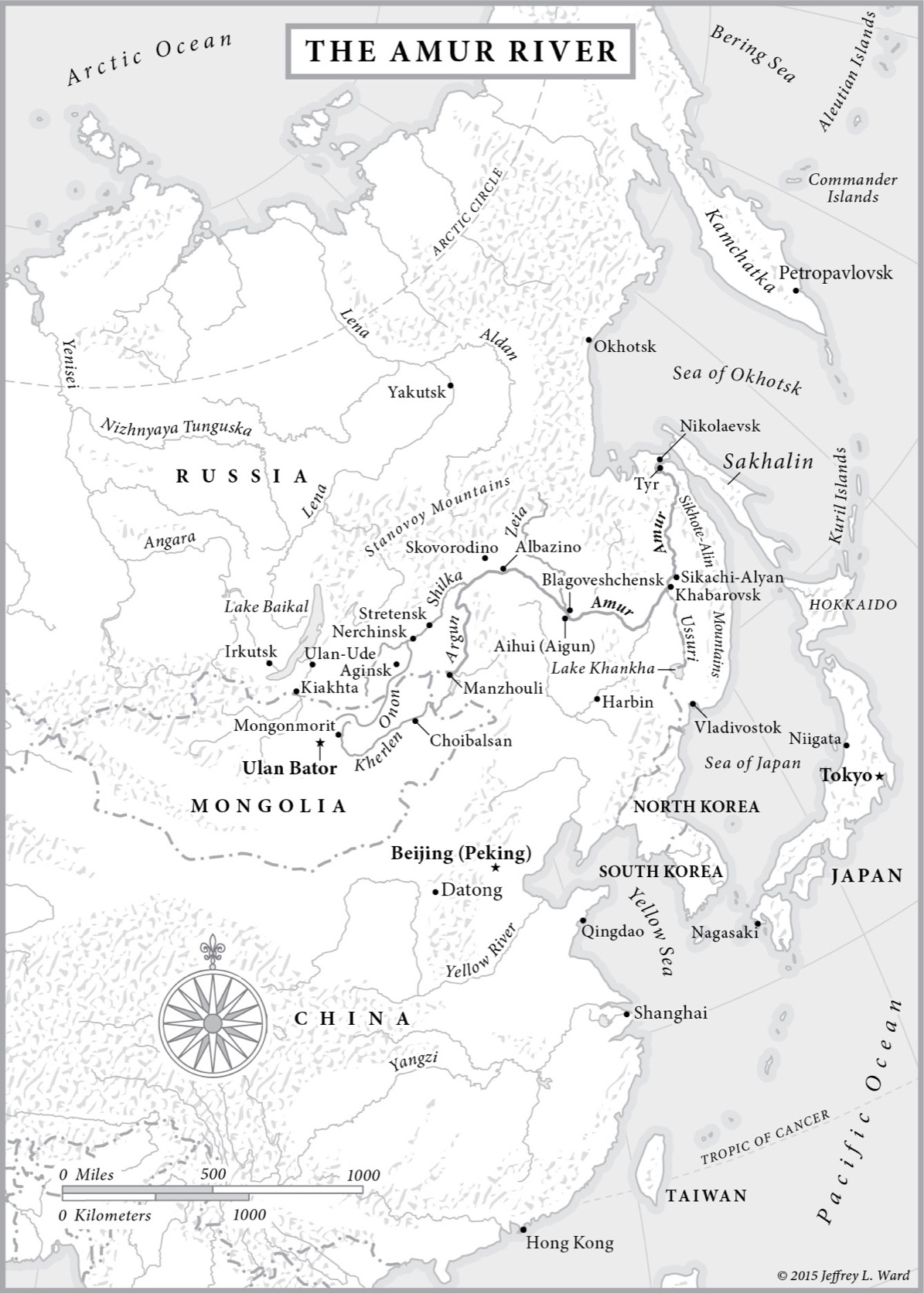

T he Amur, no commonplace river, is well worth following. It is the only major river in Siberia that runs not north into the Arctic Sea but east into the Pacific Ocean. If you measure the river from the most distant of its sources, it is the worlds ninth-longest: at 2,826 miles, it is longer than the Congo or the Mekong, and it drains a basin bigger than the Yangzis. People rarely do measure from the source, for no very sound reason, preferring to start halfway down where the Shilka and the Argun tributaries, both respectable waters in their own right, join to form the Amur proper. Even from this point the Amur is impressive, with 1,755 miles still to run till the sea. To the north of the river is the great Russian empire, to the south the Chinese one.

As the long reel of the rivers story turns, many peoples flicker in and out of view as they move along the Amurs banks or float upon its waters: Mongols, Evenki, Nivkh, Manchus, Daurians, Nanai, Solons, and Ulchi, to name a few; and then there were the Russians, the Chinese, the Japanese, and the Koreans. In many ways the Amur is the meeting ground for Asias great empires and peoples.

For much of my life the Amur was the longest river I had never heard of. The Amur approached me slantwise. When I was a foreign correspondent living in Beijing, I made a trip to what used to be called Manchuria and is now Chinas northeast. I flew to Harbin, the capital of Heilongjiang province. It was February, and minus 24 degrees. On the main square men with chain saws and ice picks were turning blocks of ice into artistic forms: swans, missile launchers, Chairman Mao, Father Christmas. The ice came from the Songhua River, chief tributary of the Heilongjiang itselfthe Black Dragon River, which is what the Chinese call the Amur, and they gave the name to the province. The main stream was still some way to the north, marking not just the provinces northern border, but the countrys. On the other side of the Amur, Russia began. But in Harbin you could still feelonly just, because the city was undergoing an orgy of redevelopmentthat this had once been a chiefly Russian place.

It had indeed been the largest city of European residents outside Europe, a Russian railway town at the turn of the last century that later, during the Russian civil war, was refuge to fifty thousand White Russians. Redbrick Russian buildings still lined the main street. Some city officials, spurning overcoats to go out into the punchy cold, took me to sing karaoke as the sun set. We sang Edelweiss (in Chinese) and a Mao Zedong verse about the Long March. But they all spoke Russian, and we also sang the Song of the Volga Boatmen in as doleful a bass as the vodka enabled.

The officials then took me to a surviving Russian restaurant. No Russians, it is true, were serving there, only Chinese. But the food came as a shock after Chinas usual fabulous fare. I was served a bowl in which a gray piece of Amur salmon swam in a greasy slop. This was ukha, I was told (there was no choice), Russias traditional fish soup. Later in the Russian Far East I discovered that there, too, this wonderful reviving soup could on occasion be prepared by unloving hands. The Chinese-made ukha in front of me looked inedible. But my waitress would not set it on the table until I had paid up front for it. That also happened to me in Russia, later. But only in Harbin did it ever happen to me in China.

On that visit, the Amur was just a presence, felt but not seen. A few years later, on a winter flight from London to Tokyo, where by now I was living, I pulled up the blind after a fitful night, a couple of hours before we were to land. The sun was low, and the clouds had cleared. Below, all was a wilderness picked out by brilliant shafts of light. The taiga was cut through by a broad white ribbon that snaked north and then, on the far fringe of the curving earth, turned purposefully east before debouching, stillborn, into a frozen sea. Along the length of this forceful river I struggled to find human signs. I was smitten.

I resolved to find out more about the Amur. I learned that the modern history of the river is the story of Russias push across the Eurasian landmass, and the story of its unanticipated meeting with China. It was in the Amur watershed that China signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk with Russia in 1689, its first treaty with a European power and one that regulated the two countries relations for nearly two centuries. To this day China views Russia differently from other Europeans. At Nerchinsk, the terms very much suited China, for they held Russians at bay. Nerchinsk was a treaty negotiated on the basis of strict equality. Later, in the nineteenth century, a stricken China was forced into a series of unequal treaties with Western powers. Today the Chinese state nourishes its schoolchildren on a diet of victimhood at the hands of Western imperialists. Russia in the nineteenth and early twentieth century was every bit the imperialist, joining Britain, France, Germany, the United States andlatermilitarist Japan, in carving China up. But today Russias part has been forgiven or forgotten, or considered somehow different.

This has very little to do with a shared history of Communism in the twentieth century. Indeed, Sino-Soviet fraternity crumbled following the death of Stalin in 1953, not long after the founding of the Peoples Republic of China. Mao Zedong ensured that antagonisms grew, and in 1969 a skirmish broke out on the ice of the Amur River that threatened to spark a more general conflagration along the whole 2,700-mile frontier. But in China, all that goes largely unmentioned.

Above all, apparently forgiven and forgotten (for now) in a country that cherishes its humiliations is a garguantan Russian grab of territory from China the scale of which dwarfs all the better remembered Western depredations in the Victorian periodHong Kong, Shanghai, and the other Treaty Ports. This imperialist grab was very different from the others, driven as they were by hardheaded and well-informed calculations of power and profit. Rather, for a couple of decades around the middle of the nineteenth century, the Amur River was at the heart of an extravagant delusion that gripped the people of a stagnant autocratic Russia under Czar Nicholas I who were all too ready to share in an episode of mad escapism. Russians rediscovered a river that for centuries had hung forgotten on the eastern edge of their realm, flowing through empty Chinese lands. They knew almost nothing of this river and its watershedneither its physical aspects nor, really, who dwelled there. All the better: onto this river they first projected dreams of mineral and agricultural wealth, and then dreams of national renewal. This river-road was to be Russians route to greatness. Above all, it seemed to offer a golden chance for Russia to replace an oppressive European identity with a vibrant one facing the Pacific. Thanks to the Amur, Russiaground down by czarist absolutism, its peasantry enserfed, and even its aristocrats admitting the country to be at a dead endcould contemplate a hopeful future.